Although torsion has distinct sonographic signs, it remains a clinical diagnosis that US findings may or may not support. Correct diagnosis often is the purview of expert sonographers and sonologists.

When ovarian torsion is present, the ovaries are enlarged and hyperechoic, their follicles pushed toward the surface (FIGURE 5A–5C). The ovaries are also tender to the touch and typically demonstrate no blood flow by Doppler interrogation. On occasion, when arterial flow is still present (venous flow is usually the first characteristic to vanish), a twisted arterial pattern may result, similar to the coil of a telephone cord. Some pelvic fluid may also appear.

Tubal torsion is harder to diagnose. US recognition depends on the finding of a normal ovary with intact blood flow beside a fluid-filled, thin-walled, tender, cystic structure with some of the previously mentioned sonomarkers of tubal occlusion such as the bead-on-a-string or cogwheel sign (FIGURE 5D–5G).

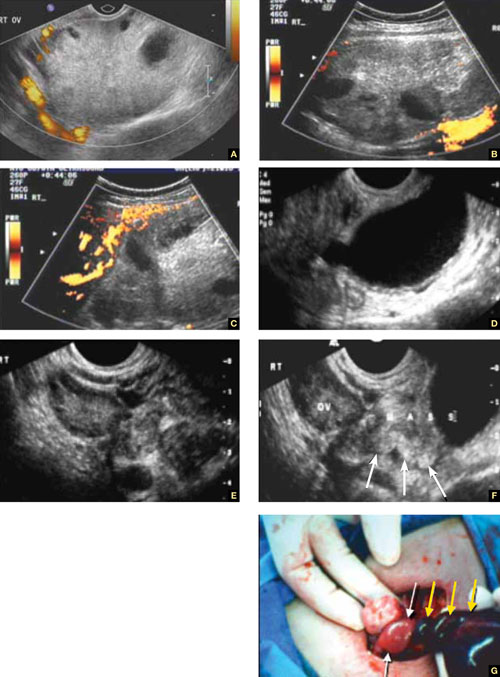

FIGURE 5 Torsion

A–C. Ovarian torsion. Hyperechoic, large ovary with follicles pushed toward the surface. Power Doppler reveals no blood flow in the ovary. D–F. Tubal torsion. Cystic dilatation with a small beak and a normal ovary. G. Intraoperative view of the tube (twisted three times; yellow arrows) and the normal ovary (white arrows).

Fluid in the cul-de-sac

In many cases, fluid may be present or trapped in the lesser pelvis, surrounded or blocked by the pelvic organs. If this fluid is the result or sequela of PID, thin, thread-like adhesive strands will be visible between the organs on US, betraying its pathogenesis (FIGURE 6). The “walls” of such loculated fluid are the pelvic wall itself and the surrounding organs.

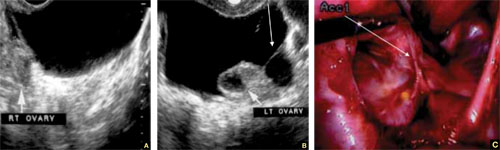

FIGURE 6 Fluid in the cul-de-sac

Sequelae of acute PID. A. Free pelvic fluid, also known as pelvic, peritoneal, loculated fluid. B. A normal ovary and an adhesive strand (arrow). C. Laparoscopic image of the adhesion (arrow).

Cancer of the tubes is unlikely, but it’s best to keep it in mind

Primary cancer of the fallopian tubes accounts for only 1% to 2% of all gynecologic cancers.2 Only 300 to 400 women are given this diagnosis each year in the United States— most of them postmenopausal.

Despite its rarity, fallopian-tube cancer is a major concern when a tubal mass is identified by palpation or imaging. In most cases, however, no palpable mass is found at the time of first examination, and tubal malignancy is diagnosed perioperatively or postoperatively.

US characteristics of tubal cancer are similar to those of ovarian cancer: a bizarre appearance, with extremely vascular tissue. At times, US attributes of tubal pathology, such as incomplete septae and tube-like fluid-filled structures, are apparent (FIGURE 7).

Consider cancer of the fallopian tube whenever an unexplained solid mass is palpated or imaged in the area of the tubes in conjunction with apparently normal ovaries.

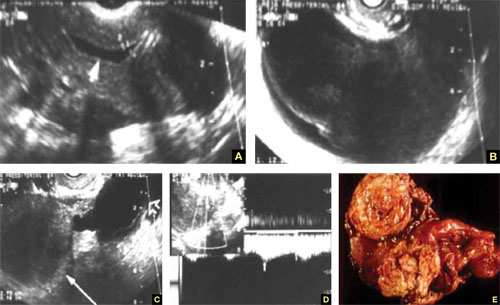

FIGURE 7 Fallopian tube cancer

A. Fluid-filled uterine cavity. B. Large cystic dilatation of the tube. C. A thickened tubal wall (arrow). D. Doppler interrogation reveals high diastolic flow (arrows). E. Macroscopic gross appearance.

The long view

As technology has advanced, so has ultrasonography. High-resolution transducers, color and power Doppler, and three-dimensional imaging make it possible for an experienced practitioner to identify and confirm the diagnosis of many adnexal masses and pathologies, from the corpus luteum to fallopian tube torsion. As the field continues to evolve, we expect that this modality will facilitate the diagnosis of adnexal abnormalities to an even greater degree.

In the meantime, this four-part tutorial offers guidance on the identification of adnexal masses. If we’ve helped ease coordination of care between the generalist ObGyn and the expert sonographer, we’ve accomplished our goal.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.