No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

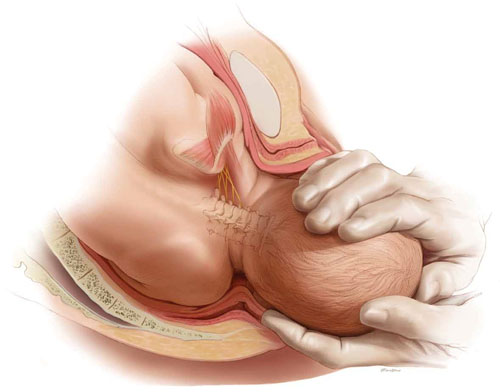

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.

But training alone cannot overcome the fact that communication is a double-sided activity: Patients bring many of their own variables to a dialogue. How patients understand and interact with you—and with other providers and the health-care system—is not, therefore, directly or strictly within your sphere of influence.

Yet your sensitivity to a patient’s issues can go a long way toward ameliorating her misconceptions and prejudices. Here are several suggestions, developed by others, to optimize patients’ understanding of their care2,3:

- Apply what’s known as flip default. Assume the patient does not understand the information that you’re providing. Ask her to repeat your instructions back to you (as is done with a verbal order in the hospital).

- Manage face-to-face time effectively. Don’t attempt to teach a patient everything about her care at once. Focus on the critical aspects of her case and on providing understanding; use a strategy of sequential learning.

- Reduce the “overwhelm” factor. Periodically, stop and ask the patient if she has questions. Don’t wait until the end of the appointment to do this.

- Eliminate jargon. When you notify a patient about the results of testing, for example, clarify what the results say about her health and mean for her care. Do so in plain language.

- Recognize her preconceptions. Discuss any psychosocial issues head on with the patient. Use an interpreter or a social worker, or counselors from other fields, as appropriate.

Remember: All health-care personnel need to understand the importance of making the patient comfortable in the often foreign, and sometimes sterile, milieu of the medical office and hospital.

Key concept #2

TRUST

Trust between patient and clinician is, we believe, the most basic necessity for ameliorating allegations of malpractice—secondary only, perhaps, to your knowledge of medicine.

Trust can be enhanced by interactions that demonstrate to both parties the advisability of working together to resolve a problem. Any aspect of the physician-patient interaction that is potentially adversarial does not serve the interests of either.

We encourage you to construct a communication bridge, so to speak, with your patient. Begin by:

- introducing yourself to her and explaining your role in her care

- making appropriate eye contact with her

- maintaining a positive attitude

- dressing appropriately

- making her feel that she is your No. 1 priority.

There is more.

Recognize the duality of respect

- Ask the patient how she wishes to be addressed

- Ask about her belief system

- Explain the specifics of her care without arrogance.

Engender trust

- Be honest with her

- Be on her side

- Take time with her

- Allow her the right that she has to select from the options or to refuse treatment

- Disclose to the patient your status as a student or resident, if that is your rank.