Few reliable data suggest that adhesions cause pelvic pain, or that adhesiolysis relieves such pain.3 Furthermore, it may be impossible to predict with reasonable probability where adhesions may be located preoperatively or to know with certainty whether a portion of the intestine is adherent to the anterior abdominal wall directly below the usual subumbilical entry site. Because of the likelihood of adhesions in a patient who has undergone two or more laparotomies, it is risky to thrust a 10- to 12-mm trocar through the anterior abdominal wall below the navel.

A few variables influence the risk of injury

The trocar used in laparoscopic procedures plays a role in the risk of bowel injury. For example, relatively dull reusable devices may push nonfixed intestine away rather than penetrate the viscus. In contrast, razor-sharp disposable devices are more likely to cut into the underlying bowel.

Body habitus is also important. The obese woman is at greater risk for entry injuries, owing to physical aspects of the fatty anterior abdominal wall. When force is applied to the wall, it moves inward, toward the posterior wall, trapping intestine. In a thin woman, the abdominal wall is less elastic, so there is less excursion upon trocar entry.

Intestinal status is another variable to consider. A collapsed bowel is unlikely to be perforated by an entry trocar, whereas a thin, distended bowel is vulnerable to injury. Bowel status can be determined preoperatively using various modalities, including radiographic studies.

Careful surgical technique is imperative. Sharp dissection is always preferable to the blunt tearing of tissue, particularly in cases involving fibrous adhesions. Tearing a dense, unyielding adhesion is likely to remove a piece of intestinal wall because the tensile strength of the adhesion is typically greater than that of the viscus itself.

Thorough knowledge of pelvic anatomy is essential. It would be particularly egregious for a surgeon to mistake an adhesion for the normal peritoneal attachments of the left and sigmoid colon, or to resect the mesentery of the small bowel, believing it to be an adhesion.

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries (FIGURE 1). Any surgeon who utilizes an energy device is obligated to protect the patient from a thermal injury—and the manufacturers of these instruments should provide reliable data on the safe use of the device, including information about the expected zone of conductive thermal spread based on power density and tissue type. As a general rule, avoid the use of monopolar electrosurgical devices for intra-abdominal dissection.

Adhesiolysis is a risky enterprise. Several studies have found a significant likelihood of bowel injury during lysis of adhesions.4-6 In two studies by Baggish, 94% of adhesiolysis-related injuries involved moderate or severe adhesions.5,6

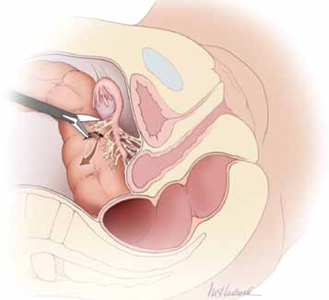

FIGURE 1 Use of energy devices is risky near bowel

Energy devices account for a significant number of intestinal injuries. In this figure, the arrow indicates leakage of fecal matter from the bowel defect.

Is laparoscopy the wisest approach?

It is important to weigh the risks of laparoscopy against the potential benefits for the patient. Surgical experience and skill are perhaps the most important variables to consider when deciding on an operative approach. A high volume of laparoscopic operations—performed by a gynecologic surgeon—should translate into a lower risk of injury to intra-abdominal structures.7 That is, the greater the number of cases performed, the lower the risk of injury.

Garry and colleagues conducted two parallel randomized trials comparing 1) laparoscopic and abdominal hysterectomy and 2) laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy as part of the eVALuate study.8 Laparoscopic hysterectomy was associated with a significantly higher rate of major complications than abdominal hysterectomy and took longer to perform. No major differences in the rate of complications were found between laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy.

In a review of laparoscopy-related bowel injuries, Brosens and colleagues found significant variations in the complication rate, depending on the experience of the surgeon—a 0.2% rate of access injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.06% for those who had performed more than 100 cases, and a 0.3% rate of operative injuries for surgeons who had performed fewer than 100 procedures versus 0.04% for more experienced surgeons.7

A few precautions can improve the safety of laparoscopy

If adhesions are known or suspected, primary laparoscopic entry should be planned for a site other than the infra-umbilical area. Options include:

- entry via the left hypochondrium in the midclavicular line

- an open procedure.

However, open laparoscopic entry does not always avert intestinal injury.9-11

If the anatomy is obscured once the abdomen has been entered safely, retroperitoneal dissection may be useful, particularly for exposure of the left colon. When it is unclear whether a structure to be incised is a loop of bowel or a distended, adherent oviduct, it is best to refrain from cutting it.