Imagine this: Your 20-year-old daughter tells you she wants to attend an expensive school for 5 years of intensive postgraduate training, amassing tens of thousands of dollars of debt, to provide expert services to the US population. There is no good substitute for the services she hopes to provide, and they are vitally needed. The services also carry risk. Despite this, she tells you that her salary will not increase every year in tandem with the cost of living; in fact, she expects her salary to be cut by nearly one-third each year. Compensation in her chosen field hasn’t increased in real dollars for many years.

Sound like a good plan?

By now you have recognized this as your own story, at least if you’re among the 92% of ObGyns who participate in Medicare.

ObGyn participation in the Medicare program reflects ObGyn training and commitment to serve as lifelong principal care physicians for women of all ages, including women with disabilities. Fifty-six percent of all Medicare beneficiaries are women. With continuing shortages of primary care physicians and the transitioning of the Baby Boomer generation to Medicare, it is likely that ObGyns will become more involved in delivering health care to this population.

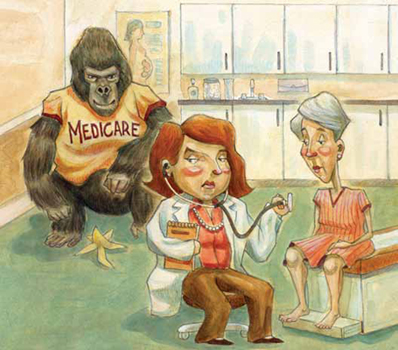

Medicare physician payments matter to ObGyns in other ways, too, because TRICARE and private payers often follow Medicare payment and coverage policies. Clearly, the Medicare program is a pretty big gorilla in every exam room. We all have much at stake in ensuring a stable Medicare system for years to come, starting with an improved physician payment system.

In 2011, Medicare paid $68 billion for physician care provided to nearly 50 million elderly and disabled individuals—about 12% of total Medicare spending—covering just over 1 billion distinct physician services. Physicians received a 10-month reprieve from a 27% cut in Medicare payments that had been scheduled for March 1, 2011, extending current payment rates through the end of this year. The agreement is part of a deal to extend a payroll tax cut and unemployment benefits. It is the 14th short-term patch to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) in the past 10 years. On January 1, 2013, we now face a 26.5% cut that Congress will have to find $245 billion to eliminate altogether.

How did we get here?

In 1997, Congress passed the Balanced Budget Act (BBA), at a time when many members of Congress were frustrated by continued increases in Medicare costs, fueled on the physician side, in part, by increases in the number of visits, tests, and procedures. To control these costs, Congress included in the BBA a complicated formula to peg Medicare physician payments to an economic growth target—the SGR. For the first few years, Medicare expenditures stayed within the target, and doctors received modest pay increases. But in 2002, expenditures rose faster than the SGR, and doctors were slated for a 4.8% pay cut.

Every year since, the SGR has signaled physician pay cuts, and every year, Congress has stopped the cuts from taking effect. But each deferral just made the next cut bigger and increased the price tag of stopping each pay cut. Today, the price of eliminating the SGR is $245 billion over the next 10 years. In these days of sequestration and deficit reduction, $245 billion is hard to find.

What now?

The good news is that support for eliminating the SGR is bicameral and bipartisan, rare in these hyperpartisan political days. Both Republicans and Democrats in the US House and Senate agree: The SGR has got to go. It’s a topic of conversation that wore out its welcome long ago.

The bad news? The $245 billion price tag. Remember, the SGR is in statute, so it requires an Act of Congress, signed by the President, to repeal it—and every Act is scored by the Congressional Budget Office.

The likeliest scenario is one we’ve seen many times before: Congress returns from a difficult election for a short, lame-duck session, during which it will have to address the cut before January 1. A real solution won’t be within reach, so Congress will likely kick that well-dented can a few more yards down the road, delaying the cut for yet another legislative cliffhanger.

In October 2012, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) joined the American Medical Association (AMA) and 110 state and national medical societies in providing the US Congress with a clear and definitive document—Driving Principles and Core Elements—that describes a way to transition to a Medicare payment system that will endure and ensure high-quality care for the individuals who rely on that program, and for many millions more whose care is linked to Medicare payment policies.