Women with ER-positive breast cancer may soon extend tamoxifen therapy to 10 years

Janelle Yates (February 2013)

Is overdiagnosis of breast cancer common among women screened

by mammography?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2013)

Breast cancer genome analysis highlights 4 subtypes, link to

ovarian cancer

Janelle Yates (News for Your Practice; November 2012)

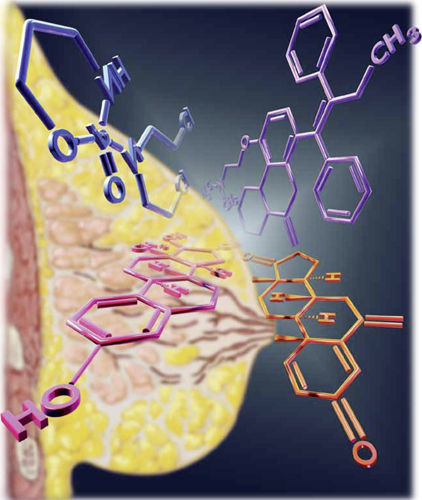

The effects of breast cancer on obstetric and gynecologic practices are pervasive. In this article, we touch on three aspects of breast cancer that are particularly relevant to the practicing ObGyn:

- the need to identify women at high risk for breast cancer and select those who would benefit from a discussion of the advantages and risks of chemoprophylaxis, which can reduce the likelihood of breast cancer by 50% or more

- the need for strategies to manage menopausal symptoms in the general population without increasing the risk of breast cancer. The traditional approach to this problem changed dramatically with the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), which demonstrated an increased risk of breast cancer in women taking conjugated equine estrogen and progestin. The widely publicized initial findings of the estrogen-progestin arm of the WHI sharply contrast the equally relevant, somewhat unexpected, and less publicized results of the estrogen-alone arm, which demonstrated a substantial and statistically significant decrease in the incidence of breast cancer, even after estrogen was discontinued.

- the potential effects of breast cancer treatment on ovarian function in young women. This year, of the approximately 250,000 women who will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, more than 50,000 women will be of reproductive age. Most of these young women will require adjuvant chemotherapy; as a result, many will experience the premature onset of menopause. Along with the attendant loss of fertility these women will face, many will also develop distressing and life-altering menopausal symptoms. Management of these women before and after initiation of chemotherapy requires an understanding of both the expected effects of the chemotherapy and knowledge of how to actively manage these women with strategies to either prevent these events or to manage menopausal symptoms.

In women at normal risk for breast cancer, unopposed estrogen lowers the rate of the malignancy and the likelihood of mortality if the cancer occurs—but is not recommended as a prophylactic agent. Tamoxifen and other chemoprophylactic drugs can halve the rate of breast cancer in high-risk women but are not without drawbacks.

A look at the lower rate of breast cancer in the estrogen-alone arm of the WHI

Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):476–486.

From 1993 through 1998, the WHI enrolled 10,739 postmenopausal women in the largest prospective trial evaluating the effect of hormone therapy (HT) on various clinical outcomes. The women were randomly allocated to three groups:

- conjugated estrogen with medroxyprogesterone acetate

- conjugated estrogen alone (in women with a prior hysterectomy)

- placebo.

The negative effects of estrogen plus progestin on the risk of breast cancer were the most widely discussed oucomes.1 Shortly after the findings from this arm of the study were published, the use of HT in the United States declined dramatically and unequivocally.2

In 2012, WHI published the results of the estrogen-alone arm in the British cancer specialty journal Lancet Oncology. As shown in the TABLE below, the incidence of breast cancer was statistically significantly lower (23%) in the estrogen group than in the placebo group. Women who were treated with estrogen alone were also 63% less likely to die of breast cancer, and all-cause mortality was 38% lower; both of these findings were statistically significant. Not only was there a significant reduction in the incidence of invasive breast cancer while the subjects were taking estrogen, but that reduction continued for a median of 4.7 years of follow-up after discontinuation of estrogen.

Breast cancer incidence and mortality in the estrogen-only arm of the WHI, compared with placebo*

| Event | Estrogen only (n = 5,310) | Placebo (n = 5,429) | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive breast cancer | 151 (0.27%) | 199 (0.35%) | 0.77 (0.62–0.95) |

| Node-negative breast cancer | 88 (0.16%) | 134 (0.24%) | 0.67 (0.51–0.88) |

| Breast cancer mortality | 6 (0.009%) | 16 (0.024%) | 0.37 (0.13–0.91) |

| All-cause mortality | 30 (0.046%) | 50 (0.076%) | 0.62 (0.39–0.97) |

| * Median follow-up of 11.8 years | |||

The incidence figure is somewhat remarkable (199 in the placebo group versus 151 in the estrogen-alone group) in that it was nearly the exact reverse of the estrogen-progestin arm of the WHI trial (199 in the estrogen/progestin group vs 150 in the placebo group).3

Estrogen alone reduced both breast cancer incidence and breast cancer mortality while women were on therapy and for 5 years after discontinuing therapy. This finding should reassure women who have undergone hysterectomy, as well as their clinicians, that estrogen alone reduces the future likelihood of breast cancer. It should be noted that the effect of estrogen alone in women in higher-risk categories did not show a reduction in breast cancer, and for this reason, the authors cautioned against considering the use of estrogen alone in menopausal women as a breast cancer chemoprophylaxis agent.