Surgical Techniques

Anatomy for the laparoscopic surgeon

Laparoscopic surgery is a safe and effective option for many patients, provided the surgeon knows the relevant anatomic landmarks and variations...

Letters from readers

-Insertion of devices at 90˚ to the umbilicus is not safe for overweight and obese women

-Two key ACA contraceptive controversies

-Believes outlet forceps delivery is sometimes justified

Insertion of devices at 90˚ to the umbilicus is not safe for overweight and obese women

I read with interest the article entitled “Anatomy for the laparoscopic surgeon” written by Mikhail and colleagues. Although I have no problem with most of this article, I strongly disagree with the recommendation to insert the Veress needle and/or entry trocar as pictured (FIGURE 3). The article states that a 90˚ angle for insertion of the aforesaid devices is safe and recommended for overweight and obese women. Unfortunately, this is not good advice.

The basis for the authors’ suggestion is an article by Hurd and colleagues,1 who conducted a retrospective review of computed tomography (CT) in three groups of women based on body mass index. There were 15 women in the nonobese group, 10 in the overweight group, and 10 in the obese group. The researchers state that the umbilicus is caudal to the aortic bifurcation in the overweight and obese groups. Thus, “… a technique in which both the Veress cannula and the primary trocar are placed near 90˚ from the horizontal appears to be appropriate in obese women.”1

Mikhail and colleagues’ recommendation has appeared in earlier publications, but I doubt the referenced source was actually read in its original form. In their results section, Hurd and colleagues states that three out of 10 women (33%) in both the overweight and obese groups had their umbilicus located at the same level as the aortic bifurcation.1 The advice to insert needles or trocars at 90˚ angles is based on a total of seven women in each of the overweight and obese groups. This is a pitifully small number of cases to base an important clinical decision, which, if wrong, could lead to a catastrophic injury to the patient.

In addition, Hurd and colleagues omit that, if the aortic bifurcation is above the umbilicus in the seven women cited, and you as the surgeon, aim the Veress needle and trocar at a 90˚ angle, you will be directly over the left common iliac vein.

It is worth noting that the 1992 Hurd article was preceded by a similar study by Hurd and colleagues2 in 1991 that was also based on imaging studies and small numbers—with a total of 19 in the over-73-kg group (nine in the overweight group and 10 in the obese group).

By contrast, when Dr. Narendran and I prospectively studied 101 women who underwent laparoscopy with pneumoperitoneum, we performed 654 measurements.3 Our data differed from Hurd and colleagues1 in several areas but, most critically, we observed that static measurements are deceiving compared with kinetic actuality. Obese women were found to have great elasticity to their anterior abdominal wall, such that when a force (a trocar) is pushed inward, the static measured distance between the anterior abdominal wall and the posterior retroperitoneum diminished significantly. Holding the abdominal wall up with one’s hand did little to alter the aforesaid dynamic.

According to data that I have published about major-vessel injury during laparoscopic operations performed by gynecologists,4,5 the patient most at risk for injury to the great vessels is the obese woman. Trocar entry at or about 90˚ is the major factor for injury. Venous injuries are worse than arterial injuries; in either case, mortality is about 20%. I am now preparing an updated version of the major vascular injury paper5 that will be based on 60 cases. Unfortunately, the same risk factors remain.

Insertion of needle and trocar devices at 90˚ to the umbilicus is not safe for overweight and obese women and, in fact, is akin to playing Russian roulette.

Michael Baggish, MD

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of California–San Francisco; The Women’s Center, St. Helena Hospital, St. Helena, California

References

Laparoscopic surgery is a safe and effective option for many patients, provided the surgeon knows the relevant anatomic landmarks and variations...

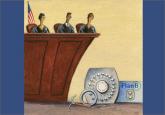

Contraception now is covered for most insured patients, but two cases before the Supreme Court could unravel this new guarantee

New data confirm that the combination of forceps and vacuum extraction should be avoided and demonstrate that use of midcavity rotational forceps...