The rise in U.S. suicide rates to the highest levels in almost 30 years is tied to many factors. One fact is clear – some experts say – the lack of training in suicide risk assessment among mental health and substance abuse clinicians is an issue that must be addressed.

“There are mental health professionals who have little to no training in suicide risk assessment,” Dr. Michael F. Myers, professor of clinical psychiatry at State University of New York, Brooklyn, said in an interview.

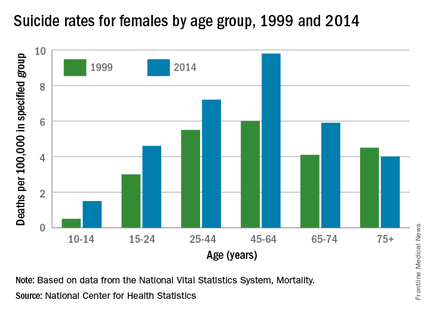

According to a report released April 22 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suicide is the 10th-leading cause of death in the United States. It increased by 24% from 1999 to 2014 overall, and the groups most dramatically affected were girls aged 10-14 years, and men aged 45-64. Women aged 45-64 and men aged 75 years and older had the highest suicide rates. About 40,000 Americans a year take their own lives, which is double the number of homicides in the country annually.

After 2006 – against the backdrop of a tough economy and a burgeoning opioid crisis – the suicide rate accelerated. Meanwhile, overall mortality from causes such as cardiovascular disease and cancer is on the decline, according to the CDC report.

Standards vary

In 2012, the American Association of Suicidology reported in its suicide prevention recommendations that less than a quarter of social workers had received any formal suicide prevention training which, when offered, usually lasted 4 hours or fewer. Only 6% of marriage and family therapists had received any such training. Psychiatry residency programs were found to offer training 91% of the time.

But in 2014, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation statement on the efficacy of suicide risk screening concluded that the evidence was insufficient to warrant allocating resources to it (Ann Int Med. 2014;160[10]:719-26). The USPSTF, however, does recommend that primary care professionals screen for depression in adults and adolescents, and earlier this year, updated its recommendations to screen pregnant women in particular (JAMA. 2016;315[4]380-7).

Also, this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services required its providers to screen patients for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).

Dr. Myers thinks this is a good starting point, but said that adding more suicide-specific questions to the depression screening process could save more lives.

Despite the USPSTF’s recommendation, investigators for a systematic review published in 2005 concluded that “Physician education in depression recognition and treatment and restricting access to lethal methods reduce suicide rates” (JAMA. 2005;294[16];2064-74). There is some federal support for implementation of suicide prevention in the primary and mental health care settings. In 2012, the U.S. Surgeon General’s office and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention jointly released the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, which cited as its No. 1 priority, the integration of suicide prevention into health care reform through initiatives such as the Zero Suicide campaign. Sponsored by the Suicide Prevention Resource Council, and funded in part by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the program aims to close the gaps in care that distract or otherwise hinder caring for and following through with patients who are at risk for suicide.

An unevenly trained mental health workforce was targeted earlier this month by members of the National Academies of Sciences who, in a report, criticized the current state of siloed mental health care, saying it results in stigmatization and undertreatment of mental illness. The authors urged Congress to empower the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to oversee better implementation and coordination of evidence-based services to prevent and treat mental disorders that lead to outcomes such as suicide. The report cites successful federal initiatives in England, Australia, and Canada that have notably improved mental health care in those countries. Those improvements took decades, the report notes.

Earlier prevention efforts

In 1999, then–Surgeon General David Satcher issued his Call to Action to Prevent Suicide, which lays out a comprehensive and integrated approach. In 2012, former Surgeon General Regina M. Benjamin published a National Strategy for Suicide Prevention. But without federal policy behind those efforts, the recommendations have not been implemented.

“This is not dissimilar to what happened in the HIV/AIDS epidemic, where finally, the medical community had to be mandated to get trained to treat the illness,” said Paul Quinnett, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist at the University of Washington, Spokane, and founder and CEO of the QPR Institute, a suicide prevention nonprofit.

Dr. Quinnett admits that what he sees as a lack of political will among many of his colleagues to address the suicide crisis angers him. “We can’t afford to look the other way and pretend this isn’t happening. These numbers are just crushing.”