California communities with higher numbers of nonmedically exempt school children experienced higher rates of pertussis cases in 2010.

Between 2000 and 2010, California nonmedical exemption rates went from less than 1.0% to 2.33%, with some schools reporting unvaccinated populations of 84% in 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At 9,120 cases of pertussis and 10 subsequent deaths in 2010, California recorded more statewide incidences of the disease since 1947, just after the pertussis-containing vaccines were introduced in the United States.

Investigators led by Jessica E. Atwell, M.P.H., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, recently reported data linking the two phenomena. "Our findings suggest that communities with large numbers of intentionally unvaccinated or undervaccinated persons can lead to pertussis outbreaks," Ms. Atwell and her colleagues wrote (Pediatrics 2013;132:624-30).

The 2010 outbreak previously has been attributed to waning immunity, susceptibility in the infant population, better detection rates, and adaptation by the circulating strains, yet the role of the choice to forego immunization had not previously been investigated, according to the study authors. To determine the relationship, Ms. Atwell and her team evaluated the spatial clustering of nonmedical exemptions for kindergartners in the state between the 2005-2006 and 2009-2010 school years and compared it with the space-time clustering of pertussis cases reported in the state in 2010.

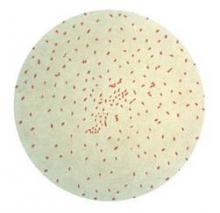

Pertussis outbreak data from the California Department of Public Health were "geocoded" and aggregated, as were the school’s exact locations, to protect patient privacy. Data for the number of kindergartners enrolled in the state, and the number of kindergartners with nonmedical exemptions also were tabulated. School enrollment and the number of nonmedical exemptions also were aggregated to the census tract level.

The investigators calculated nonmedical exemption rates by dividing the nonmedically exempted children by the total number of kindergartners enrolled in each census tract. They used spatial scan statistics to identify clusters of monthly pertussis cases, and multivariate logistic regression to determine the odds ratios (OR) for pertussis cases within or out of nonmedical exemption clusters, and to compare various demographic characteristics of each tract.

The data indicated that census tracts within a cluster of nonmedical exemptions were more likely to also be within locations with pertussis case clusters (OR, 2.47). This was true even after researchers adjusted for covariates such as race, population density, average family size, education, and income (OR, 1.73). Ms. Atwell and her team also found that the pertussis incidence rate ratio (IRR) was higher within nonmedical exemption clusters than it was outside of them (IRR, 1.20) and that the associated risk remained after adjusting for covariates (IRR, 1.12).

Two statistically significant clusters of pertussis cases, spanning from May 2010 to October 2010, and from July 2010 to November 2010, existed in central California with 3,783 observed cases out of an expected level of 1,835 (relative risk, 2.91), and in San Diego County with 980 vs. an expected level of 391 (RR, 2.71). Reported pertussis rates statewide in 2010 varied monthly from less than 100 in January to more than 1,000 in August. Nonmedical exemptions and clusters of pertussis cases, according to the authors, were associated with high socioeconomic status, lower average family size, higher education levels, lower percentages of racial or ethnic minorities, and higher income levels statewide.

Nonmedical exemption data in California does not include specifics as to which vaccines were or were not given, or any dosages; therefore, the authors wrote "it is possible that some children with a nonmedical exemption were completely vaccinated against pertussis." They suggested that "future studies should attempt to analyze varying rates of vaccine avoidance for specific antigens to determine the magnitude of impact within populations with high nonmedical exemptions."

Because their study did not include homeschooled children, the authors concluded that additional analysis should be explored. They also cited the need for future studies to include data on subgroups of the various case definitions which, in California, includes acute cough illness of any duration with polymerase chain reaction detection of Bordetella pertussis–specific nucleic acid, or one or more typical pertussis symptoms that can be epidemiologically linked to a confirmed case.

The authors did not report any relevant disclosures. The CDC funded the collection of vaccine-preventable disease and immunization data at the California Department of Public Health.