People with serious mental illness (SMI) have a life expectancy that is 25 years less than the general population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 This disparity is partially a consequence of the lack of primary and preventive medical care for those with psychiatric illness. Decades of research have shown that people with SMI experience higher medical morbidity and mortality in addition to facing the stigma of mental illness.

This article aims to advance the idea that longitudinal “cross education” between primary care providers (PCPs) and behavioral health providers (BHPs) is essential in addressing this problem. BHPs include psychiatry clinics, which often are part of a university or large health systems; county-based community mental health programs; and independent mental health clinics that contract with public and private health plans to provide mental health services.

Although suicide and injury account for 40% of the excess mortality in schizophrenia, 60% can be attributed to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases, and infection.2 Patients with SMI have 2 to 3 times the risk of diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.3,4 Furthermore, those with SMI consume more than one-third of tobacco products,5 and 50% to 80% of people with SMI smoke tobacco, an important reversible risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

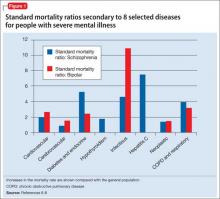

Figure 1 shows that people with SMI are at higher risk of dying from a chronic medical condition, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hepatitis C6-8—many of which can be managed by primary and preventive medical interventions. These and other conditions often are not diagnosed or effectively managed in patients with SMI.

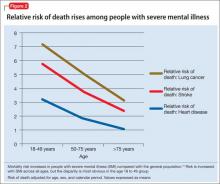

The high prevalence of metabolic syndrome and tobacco dependence among people with SMI accelerates development of cardiovascular disease, as shown by several studies. Bobes et al9 found that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk among patients with SMI is similar to what is found in the general population at 10 to 15 years of greater age. Osborn et al10 demonstrated that people with SMI age 18 to 49 had a higher relative risk of death from coronary heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer than age-matched controls (Figure 2).

It can be said, therefore, that patients with SMI seem to “age” and die prematurely. To reduce this disparity, primary and preventive medical care—especially for cardiovascular disease—must be delivered earlier in life for those with SMI.

Iatrogenic causes of morbidity

Many psychiatric medications, especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), could exacerbate cardiovascular and metabolic conditions by increasing the risk of weight gain, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia. Antipsychotics that generally are considered to be more effective for refractory psychotic illness (eg, clozapine and olanzapine) are associated with the highest risk of metabolic syndrome. Simon et al11 found a dose-response relationship between olanzapine and clozapine serum concentrations and worsening metabolic outcomes. Valproic acid also can cause significant weight gain and could require monitoring similar to what is done with to SGAs, although there has been less clinical and research attention to this mood stabilizer.

The American Diabetes Association et al12 have published guidelines on monitoring antipsychotic-induced obesity and diabetes, but adoption of these guidelines has been slow. Mackin et al13 found that providers are slow to recognize the elevated rate of obesity and dyslipidemia among psychiatric patients, possibly because of “an alarmingly poor rate of monitoring of metabolic parameters.”

Treating adverse metabolic outcomes also seems to lag behind. The same study13 found that physical health parameters among psychiatric patients continue to become worse even when appropriate health care professionals were notified. Rates of nontreatment for diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension were 30%, 60%, and 88% respectively, according to Nasrallah et al.14

Randomized controlled studies have shown that obesity and metabolic syndrome can be effectively managed using lifestyle and pharmacotherapeutic approaches,15,16 but more research is needed to test long-term outcomes and how to best incorporate these interventions. Newcomer et al17 found that gradually switching an antipsychotic with high risk of metabolic adverse effects to one with lower risk could reduce adverse metabolic outcomes; however, some patients returned to their prior antipsychotic because other medications did not effectively treat their schizophrenia symptoms. Therefore, physicians must pay careful attention to the trade-off between benefits and risks of antipsychotics and make treatment decisions on an individual basis.

Barriers to medical care

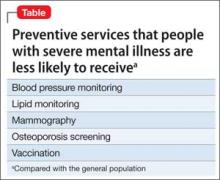

Research has demonstrated that patients with SMI receive less screening and fewer preventive medical services, especially blood pressure monitoring, vaccinations, mammography, lipid monitoring, and osteoporosis screening, compared with the general population (Table).18 Some barriers to preventive services could exist because of demographic factors and medical insurance coverage19 or medical providers’ discomfort with symptoms of SMI,20 although Mitchell et al21 found that disparities in mammography screening could not be explained by the presence of emotional distress in women with SMI.

DiMatteo et al22 reported that patients with SMI are 3 times more likely to be noncompliant with medical treatment. These patients also are less likely to receive sec ondary preventive medical care and invasive medical procedures. Those with SMI who experience acute myocardial infarction are less likely to receive drug therapy, such as a thrombolytic, aspirin, beta blocker, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.23 They also are less likely to receive invasive cardiovascular procedures, including cardiac catheterization, angioplasty, and coronary artery bypass grafting.24