The Social Security Administration (SSA) does not provide much guidance on the contentious issue of determining payeeship for disability beneficiaries. The only description available is stated on the “Physician/medical officer’s statement of patient’s capability to manage benefits” (form SSA-787): “By capable we mean that the patient: Is able to understand and act on the ordinary affairs of life, such as providing for own adequate food, housing, etc., and is able, in spite of physical impairments, to manage funds or direct others how to manage them.”

Physicians will be asked to make a capability statement if they are performing a consultative examination for SSA or if their patient:

• is applying for benefits

• needs to have a payee.

Regrettably, the published literature on capability is scant.1,2 Based on decades of personal experience, here is the approach I have adopted to determine capability.

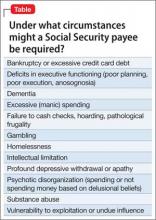

Diagnoses, circumstances, and clinical syndromes that strongly suggest the need for a payee include those listed in the Table.

The psychiatric rehabilitation agency I work at adheres to a recovery model. I consult with caseworkers on the issue of capability, but generally endorse a “team” recommendation for initiating or terminating payeeship. A number of factors are involved:

Adherence to recovery means that we encourage autonomy; we do not attempt to prevent every bad decision.

Demands for money from the patient and demands to terminate payeeship can be strident and potentially violent.

Confrontations over payeeship can be a safety risk for family or staff who have been acting as the payee.

Guardianship (or conservatorship) is a judicially determined restriction of financial decision-making.

Payeeship is an extrajudicial restriction of financial decision-making. Treating physicians, understandably, may feel uneasy restricting the rights of a patient. Additionally, there is ethical stress when a physician does anything that might compromise the primacy of the treatment relationship.

If all parties agree that payeeship should be terminated, I recommend the payee (whether the family or an institutional payee) begin a 3-month trial, during which the payee does not pay bills or keep a budget. The patient receives his (her) money in a lump sum at the beginning of the month, which begins a naturalistic trial of the patient’s capability to pay rent and budget adequately for all other necessities. If the patient demonstrates capability, I sign the SSA-787 form.

Offering a structured plan for restoring a patient’s benefits could defuse hostile demands.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.