Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to be a significant public health problem with potentially serious complications.1 The incidence of new STIs, including viral STIs, in the United States is estimated at 19 million cases per year.2Chlamydia trachomatis remains the most common bacterial STI with an estimated annual incidence of 2.8 million cases in the United States and 50 million worldwide. Second in prevalence is gonococcal infection. Herpes simplex virus is one of the most common viral STIs, but the incidence of human papillomavirus virus (HPV), which is associated with cervical cancer, has steadily increased worldwide.3 Young persons age 15 to 24 are at the highest risk of acquiring new STIs with almost 50% of new cases reported among this age group.4

STIs can have serious complications and sequelae. For example, 20% to 40% of women who have chlamydia infections and 10% to 20% of women who have gonococcal infections develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID),2 which increases the risk for ectopic pregnancy, infertility, and chronic pelvic pain.

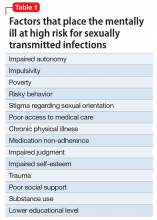

Patients with mental illness are at high risk of acquiring STIs. In the United States, the prevalence of HIV among patients with psychiatric illness is 10 to 20 times higher than in the general population.4,5 Factors contributing to increased vulnerability to STIs among psychiatric patients include:

- impaired autonomy

- increased impulsivity

- increased susceptibility to coerced sex.6

Furthermore, a higher incidence of poverty, placement in risky environments, and overall poor health and medical care also contribute to the high prevalence of STIs and their complications in this population (Table 1). Because of risk factors specific to psychiatric illness, standard STI prevention interventions are not always successful and novel and innovative behavioral approaches are necessary.7

Case Abdominal pain and fever

Ms. K, age 25, has a history of bipolar disorder treated with lithium and presents to the community psychiatrist with lower abdominal pain. She recently recovered from a manic episode and has started to reintegrate with the community mental health team. She refuses to see her primary care physician and is adamant that she wishes to see her psychiatrist, who is the only doctor she has rapport with.

Ms. K reports lower abdominal pain for 3 or 4 days and fever for 1 day. The pain is dull in character. She denies diarrhea, vomiting, or urinary symptoms, but on further questioning describes new-onset, foul-smelling vaginal discharge without vaginal bleeding. Her menstrual cycle usually is regular, but her last menstrual period occurred 2 months ago. Her medical history includes an appendectomy at age 10 and she is a current cigarette smoker. Chart notes taken during her manic episode describe high-risk behavior, including having unprotected sexual intercourse with several partners. On examination, she is febrile and tachycardic with a tender lower abdomen.