Some other sleep disruptors likely were involved in Mr. R’s case. Auditory and tactile stimuli are known to cause cortical arousals, with additive effect seen when these 2 stimuli are combined.3,14 Additionally, these exogenous stimuli are known to trigger sleep-related violent parasomnias.15 Mr. R displayed this behavior after his wife woke him up. The auditory stimulus of his wife’s voice and/or tactile stimulus involved in the act of waking Mr. R likely played a role in the suicidal and violent nature of his NREM parasomnia.

The authors’ observations

In general, the mechanisms by which zolpidem causes NREM parasomnias are not completely understood. The sedation-related amnestic properties of zolpidem might explain some of these behaviors. Patients could perform these behaviors after waking and have subsequent amnesia.4 There is greater preservation of Stage N3 sleep with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines also cause muscle relaxation while the motor system remains relatively more active during sleep with zolpidem because of its selectivity for α-1 subunit of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor. These factors might increase the likelihood of NREM parasomnias with zolpidem compared with benzodiazepines.4

Types of parasomnias

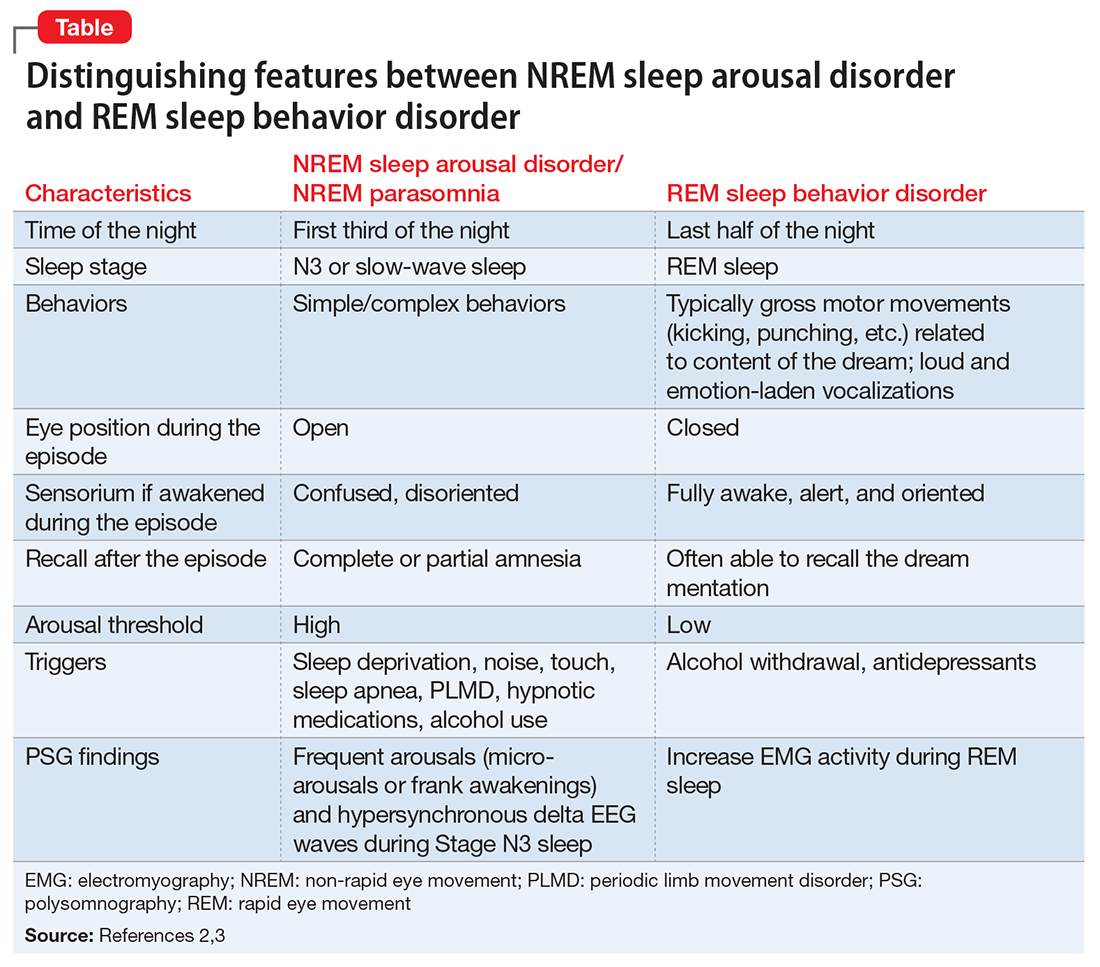

According to DSM-5, there are 2 categories of parasomnias based on the sleep stage from which a parasomnia emerges.2 REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) refers to complex motor and/or vocalizations during REM sleep, accompanied by increased EMG activity during REM sleep (Table).2,3

The pseudo-suicidal behavior Mr. R displayed likely was NREM parasomnia because it occurred in the first third of the night with his eyes open and impaired recall after the event. Interestingly, Mr. R had RBD in addition to the NREM parasomnia likely caused by zolpidem. This is evident from Mr. R’s frequent dream enactment behaviors, such as kicking, thrashing, and punching during sleep, along with increased EMG activity during REM sleep as recorded on the PSG.10 The presence of RBD could be explained by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (fluoxetine) use, and comorbidity with PTSD.2,16

Management of parasomnias

Initial management of parasomnias involves decreasing the risk of parasomnia-related injury. Suggested safety measures include:

- sleeping away from windows

- sleeping in a sleeping bag

- sleeping on a lower floor

- locking windows and doors

- removing potentially dangerous objects from the bedroom

- putting gates across stairwells

- installing bells or alarms on door knobs.15

Removing access to firearms or other weapons such as knives is of utmost importance especially with patients who have easy access during wakefulness. If removing weapons is not feasible, consider disarming, securing, or locking them.15 These considerations are relevant to veterans with PTSD because of the high prevalence of symptoms, including depression, insomnia, and pain, which require sedating medications.17 A review of parasomnias among a large sample of psychiatric outpatients revealed that a variety of sedating medications, including antidepressants, can lead to NREM parasomnias.18 Therefore, exercise caution when prescribing sedating medications, especially in patients vulnerable to developing dangerous parasomnias, such as a veteran with PTSD and easy access to guns.19

TREATMENT Zolpidem stopped

Mr. R immediately stops taking zolpidem because he is aware of its association with abnormal behaviors during sleep, and his wife removes his access to firearms and knives at night. Because of his history of clinical benefit and no history of parasomnias with mirtazapine, Mr. R is started on mirtazapine for insomnia that previously was treated with zolpidem, and residual depression. Six months after discontinuing zolpidem, he does not experience NREM parasomnias, and there are no changes in his dream enactment behaviors.

Summing up

Zolpidem therapy could be associated with unusual variants of NREM parasomnia, sleepwalking type; sleep-related pseudo-suicidal behavior is one such variant. Several factors could play a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia with zolpidem therapy. In Mr. R’s case, the pharmacokinetic drug interactions between fluoxetine and zolpidem, as well as concomitant use of several sedating agents could have played a role in increasing the likelihood of NREM parasomnia, with audio-tactile stimuli contributing to the violent and suicidal nature of the parasomnia. Exercise caution when using CYP enzyme inhibitors, such as fluoxetine and paroxetine, in combination with zolpidem. Knowledge of the potential interaction between zolpidem and fluoxetine is important because antidepressants and hypnotics are commonly co-prescribed because insomnia often is comorbid with other psychiatric disorders.

In veterans with PTSD who do not have suicidal ideations while awake, life-threatening non-intentional behavior is a risk because of easy access to guns or other weapons. Sedative-hypnotic medications commonly are prescribed to patients with PTSD. Exercise caution when using hypnotic agents such as zolpidem, and consider sleep aids with a lower risk of parasomnias (based on the author’s experience, trazodone, mirtazapine, melatonin, and gabapentin) when possible. Non-pharmacologic treatments of insomnia, such as sleep hygiene education and, more importantly, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, are preferred. If a patient is already taking zolpidem, nightly dosage should not be >10 mg. Polypharmacy with other sedating medications should be avoided when possible and both exogenous (noise, pets) and endogenous sleep disruptors (sleep apnea, PLMD) should be addressed. Advise the patient to avoid alcohol and remove firearms and other potential weapons. Discontinue zolpidem if the patient develops sleep-related abnormal behavior because of its potential to take on violent forms.