Sexting includes sending sexually explicit (or sexually suggestive) text messages and photos, usually by cell phone. This article focuses on sexts involving photos. Cell phones are almost ubiquitous among American teens, and with technological advances, sexts are getting easier to send. Sexting may occur to initiate a relationship or sustain one. Some teenagers are coerced into sexting. Many people do not realize the potential long-term consequences of sexting—particularly because of the impulsive nature of sexting and the belief that the behavior is harmless.

Media attention has recently focused on teens who face legal charges related to sexting. Sexting photos may be considered child pornography—even though the teens made it themselves. There are also social consequences to sexting. Photos meant to be private are sometimes forwarded to others. Cyberbullying is not uncommon with teen sexting, and suicides after experiencing this behavior have been reported.

Sexting may be a form of modern flirtation, but in some cases, it may be a marker of other risk behaviors, such as substance abuse. Psychiatrists must be aware of the frequency and meaning of this potentially dangerous behavior. Clinicians should feel comfortable asking their patients about it and provide education and counseling.

CASE

Private photos get shared

K, age 14, a freshman with no psychiatric history, is referred to you by her school psychologist for evaluation of suicidal ideation. K reports depressed mood, poor sleep, inattention, loss of appetite, anhedonia, and feelings of guilt for the past month. She recently ended a relationship with her boyfriend of 1 year after she learned that he had shared with his friends naked photos of her that she had sent him. The school administration learned of the photos when a student posted them on one of the school computers.

K’s boyfriend, age 16, was suspended after the school learned that he had shared the photos without K’s consent. K, who is a good student, missed several days of school, including cheerleading practice; previously she had never missed a day of school.

On evaluation, K is tearful, stating that her life is “over.” She says that her ex-boyfriend’s friends are harassing her, calling her “slut” and making sexual comments. She also feels guilty, because she learned that the police interviewed her ex-boyfriend in connection with posting her photos on the Internet. In a text, he said he “might get charged with child pornography.” On further questioning, K confides that she had naked photos of her ex-boyfriend on her phone. She admits to sharing the pictures with her best friend, because she was “angry and wanted to get back” at her ex-boyfriend. She also reports a several-month history of sexting with her ex-boyfriend. K deleted the photos and texts after learning that her ex-boyfriend “was in trouble with the police.”

K has no prior sexual experience. She dated 1 boy her age prior to her ex-boyfriend. She had never been evaluated by a mental health clinician. She is dysphoric and reports feeling “hopeless … Unless this can be erased, I can’t go back to school.”

Sexting: What is the extent of the problem?

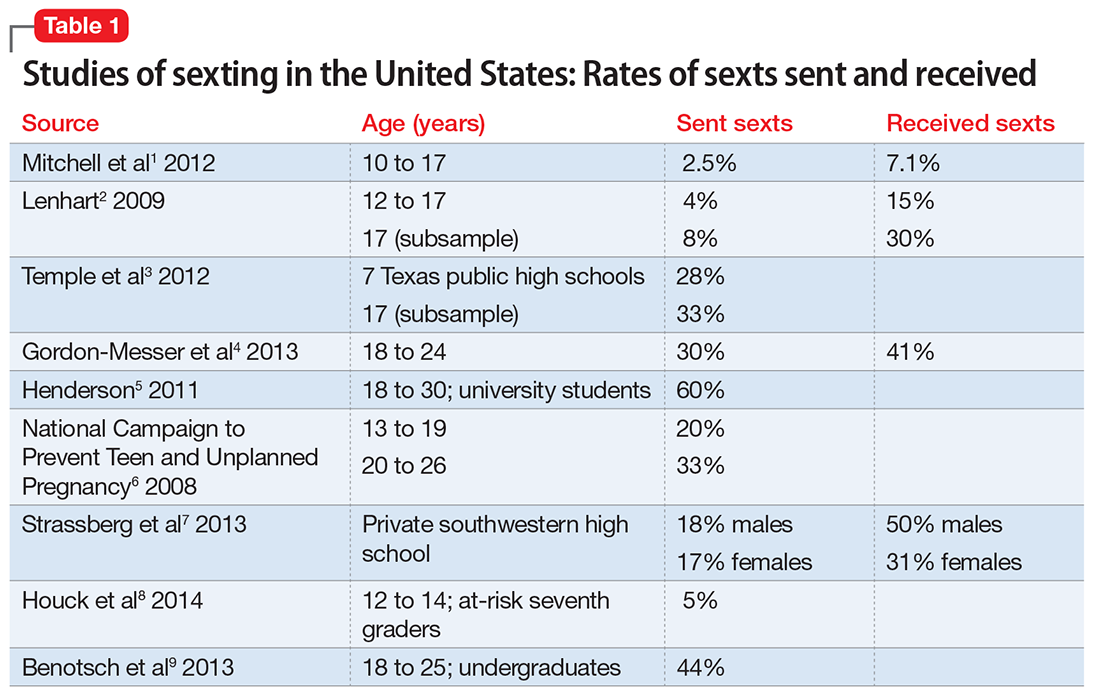

The true prevalence of sexting is difficult to ascertain, because different studies have used different definitions and methodologies. However, the rates are far from negligible. Sexting rates increase with age, over the teen years.1-3 Among American minors, 2.5% to 28% of middle school and high school students report that they have sent a sext (Table 11-9). Studies of American young adults (age ≥18) and university students have found 30% to 60% have sent sexts, and >40% have received a sext.4,5

Many people receive sexts—including individuals who are not the intended recipient. In 1 study, although most teens intended to share sexts only with their boyfriend/girlfriend, 25% to 33% had received sext photos intended for other people.6 In another recent study, 25% of teens had forwarded a sext that they received.7 Moreover, 12% of teenage boys and 5% of teenage girls had sent a sexually explicit photo that they took of another teen to a third person.7 Forwarding sexts can add exponentially to the psychosocial risks of the photographed teenager.

Who sexts? Current research indicates that the likelihood of sexting is related to age, personality, and social situation. Teens are approaching the peak age of their sex drive, and often are curious and feel invincible. Teens are more impulsive than adults. When it takes less than a minute to send a sext, irreversible poor choices can be made quickly. Teens who send sexts often engage in more text messaging than other teens.7

Teens may use sexting to initiate or sustain a relationship. Sexts also may be sent because of coercion. More than one-half of girls cited pressure to sext from a boy.6 Temple et al3 found that more than one-half of their study sample had been asked to send a sext. Girls were more likely than boys to be asked to send a sext; most were troubled by this.

One study that assessed knowledge of potential legal consequences of sexting found that many teens who sent sexts were aware of the potential consequences.7 Regarding personality traits, sexting among undergraduates was predicted by neuroticism and low agreeableness.10 Conversely, sending text messages with sexually suggestive writing was predicted by extraversion and problematic cell phone use.

Comorbidities. There are mixed findings about whether sexting is simply a modern dating strategy or a marker of other risk behaviors; age may play an important discriminating role. Sexual activity appears to be correlated with sexting. According to Temple and Choi,11 “Sexting fits within the context of adolescent sexual development and may be a viable indicator of adolescent sexual activity.”11

Some authors have suggested that sexting is a contemporary risk behavior that is likely to correlate with other risk behaviors. Among young teens—seventh graders who were referred to a risk prevention trial because of behavioral/emotional difficulties—those who sexted were more likely to engage in early sexual behaviors.8 These younger at-risk teens also had less understanding of their emotions and greater difficulty in regulating their emotions.

Among the general population of high school students, teens who sext are more likely to be sexually active.3 High school girls who engaged in sexting were noted to engage in other risk behaviors, including having multiple partners in the past year and using alcohol or drugs before sex.3 Teens who had sent a sext were more likely to be sexually active 1 year later than teens who had not.11Studies of sexting among university students also have had mixed findings. One study found that among undergraduates, sexting was associated with substance use and other risk behaviors.9 Another young adult study found sexting was not related to sexual risk or psychological well-being.4