Addiction used to be considered a moral failing, and the family was blamed for keeping the relative with addictions sick, through behaviors labeled “codependency” and “enabling.” The opioid epidemic can take credit for putting a serious dent in these destructive and stigmatizing notions. When psychiatrists actively include families as educated treatment partners, fatalities are less likely, and the havoc created by addiction on families is mitigated.

Addiction is now clearly understood as a chronic neurobiological disease. Like all chronic illnesses, better outcomes are associated with a good repertoire of coping skills and, most importantly, access to evidence-based treatment. States that place health care as a top priority have devoted time, expertise, and money to improving access and developing public policies to affect the opioid crisis. Their actions include educating physicians, challenging insurance companies that require prior authorization to cover naloxone, suing drug companies, and training communities in opioid overdose first aid. A plan such as the Rhode Island Governor’s Task Force on Opioid Addiction and Overdose is comprehensive and uses prescription drug–monitoring program data for tracking progress. That state’s four-point plan aims to reduce overdose deaths by one-third in 3 years. The state’s prevention initiative tackles co-use of benzodiazepines and opioids by creating provider guidelines on this risk. Its treatment initiative rolls out methadone- and buprenorphine-assisted treatment (medication-assisted treatment or MAT) in prisons, jails, the community, and hospitals. Rescue efforts expand naloxone as the standard of care, by providing sustainable community-based naloxone sources and naloxone at the pharmacy. The recovery initiative expands recovery centers and peer recovery support capacity, especially in the emergency department, post overdose. These efforts exemplify an integrated, coordinated, health-focused agenda aimed at addressing overdose (J Law Med Ethics. 2017 Mar;45[1_suppl]:20-3).Genes and addiction

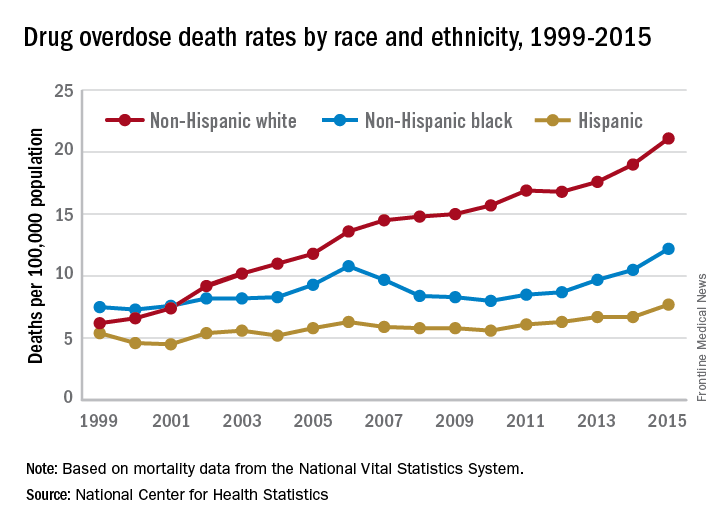

What causes addiction? Statistics show that Native Americans fare the worst of all minority groups, with death by opiates in whites and Native Americans double or triple the rates of African Americans and Latinos. Reasons put forward for Native American deaths are their vulnerability related to systemic racism, intergenerational trauma, and lack of access to health care. These “reasons” are well known to contribute to poor overall health status of impoverished communities.

Among impoverished white communities, the Monongahela Valley of Pennsylvania has been studied by Katherine McLean, PhD, as an example of postindustrial decay (Int J Drug Policy. 2016;[29]:19-26). Once a global center of steel production, the exodus of jobs, residents, and businesses since the early 1980s is thought to contribute to the high numbers of opioid deaths. A qualitative study of the people with addiction in the deteriorating mill city of McKeesport, Pa., characterized a risk environment hidden behind closed doors, and populated by unprepared, ambivalent overdose “assistants.” These people are “co-drug” users who themselves are reluctant to step forward because of fear of getting in trouble. The participants described the hopelessness and lack of opportunity as driving the use of heroin, with many stating that jobs and community reinvestment are needed to reduce fatalities. This certainly resonates with the Native American experience.

How do these environmental factors affect those with biological vulnerability? Epigenetic research shows that environmental factors influence DNA methylation, which influences gene expression, leading to differential adaptations to stress. One example involves oxytocin, which is well known to mediate intimacy and play a role in nurturing relationships. Polymorphisms of the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) result in three significant variants: GG, AG, and AA. A-allele carrier individuals are associated with more sensitivity to stress; fewer social skills; and lower scores on psychological resources, like optimism, mastery, and self-esteem; more depressive symptoms; lower psychological resources; and the lowest amygdala activation while processing emotional information. A prospective study found a relationship between DNA methylation at birth and resilience to environmental stressors in future domains such as conduct, hyperactivity, and emotional problems in childhood. In this study of 91 children, a relationship was found between pre- and postnatal adversity and OXTR DNA methylation type, and future resilience to conduct problems and other childhood disorders (Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29[5]:1663-74). Clearly, social deprivation has an impact, through epigenetics, on biological substrates such as OXTR.People with the AA variant of OXTR also have been shown to have less secure adult attachment and more social anxiety (World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17[1]:76-83). Comparing people with OXTR variants, the AA genotype was associated with a perceived negative social environment and significantly increased PTSD symptoms, whereas the GG genotype was protective.

However, for many decades, psychological theories about the defects of individuals and their moral failing have prevailed. In the family, aspersions have been cast on the family’s deficits in terms of setting limits and their enabling behaviors, mostly focusing on wives and mothers. The social mantra has been that since not all people get addicted, the strong resist and the weak succumb. Psychiatry has focused on providing psychotherapy to correct the personal deficits of the weak and addicted and, from a family perspective, on correcting negative personality traits in the caregivers, classified as codependency.