The author’s observations

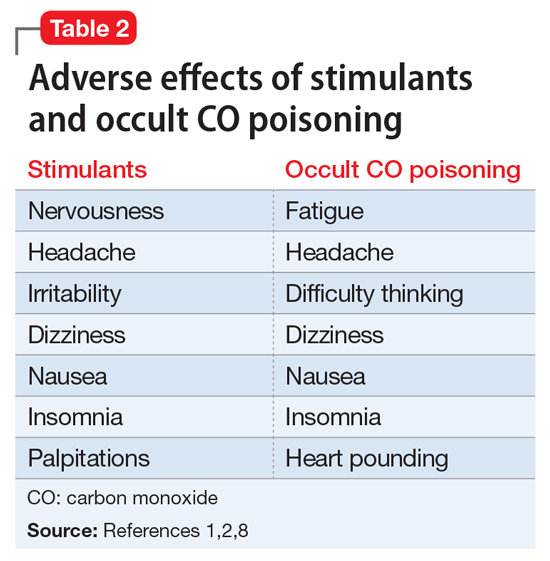

Anxiety, irritability, agitation, and palpitations can all be symptoms of stimulant medications.1,2 There are numerous other iatrogenic causes, including steroid-based asthma treatments, thyroid medications, antidepressants in bipolar patients, and caffeine-based migraine treatments. Mr. L’s theory that his 15-lb weight loss was the result of his methylphenidate ER dose being too high was a reasonable one. Often, medication doses need to be adjusted with weight changes. His decrease in energy during the day could be explained by the methylphenidate ER controlling his hyperactive symptoms, which include high energy. At night, when the medication wears off, his hyperactivity symptoms could be returning, which would account for the increase in energy when he gets home from work. Although longer-acting stimulants tend to have a more benign adverse effects profile, they can cause insomnia if they are still in the patient’s system at bedtime. Shorter-acting stimulants wear off quickly but can be advantageous for patients who want to target concentration during certain times of day, such as for school and homework.

TREATMENT A surprising cause

The next month, Mr. L presents to the emergency room complaining of jitteriness, headache, and tingling in his fingers, and is evaluated for suspected carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning. Three months earlier, he had noted the odor of exhaust fumes in the limousine he drives 7 days a week. He took it to the mechanic twice for evaluation, but no cause was found. Despite his concerns, he continued to drive the car until an older client, in frail health, suddenly became short of breath and developed chest pain shortly after entering his vehicle, on a day when the odor was particularly bad. Before that, a family of passengers had complained of headaches upon entering his vehicle. The third time he brought his car to be checked, the mechanic identified an exhaust system leak.

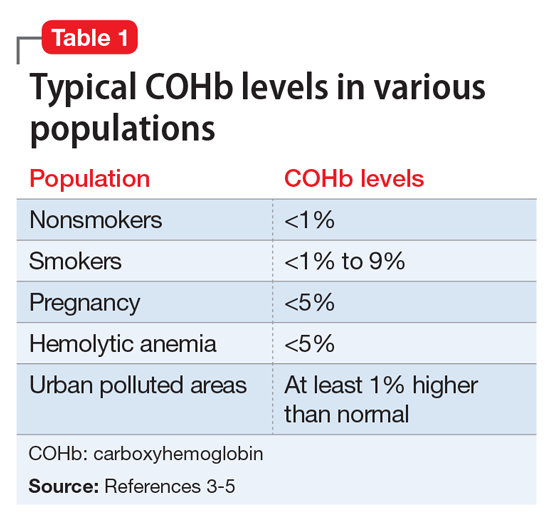

In the emergency room, work-up includes CMP, CBC, troponin, arterial blood gas (ABG), and carboxyhemoglobin (COHb) level. His CBC, CMP, and troponin levels are normal. ABG test shows low partial pressure of oxygen of 35 mm Hg (normal is 75 to 100 mm Hg) and low oxygen saturation of 71.8% (normal 92% to 98.5%). His anion gap was low at 4.7 mEq/L (normal 10 to 20 mEq/L). COHb level is significantly elevated at 5.0% (normal 0% to 1.5%) (Table 13-5). He is diagnosed with CO poisoning and treated with oxygen by mask for 2 hours. After treatment, repeat laboratory tests are normal.The author’s observations

Although CO is odorless, it is a component of exhaust fumes; thus, an odor may be present in a vehicle with an exhaust system leak, but it is not that of the CO itself.6 CO has an affinity for hemoglobin >200 times that of oxygen.7 Sources of unintentional poisoning include motor vehicle exhausts, defective heating systems, tobacco smoke, and urban pollution. Common symptoms of chronic, low-dose CO poisoning include headache, fatigue, dizziness, paresthesia, chest pain, palpitations, and visual disturbances (Table 2).1,2,8

Work-up for suspected CO poisoning includes ABG, COHb level, CBC, basic metabolic panel, EKG, cardiac enzymes, and chest radiography, as well as other laboratory tests as deemed appropriate. Treatment includes oxygen by mask for low-level poisoning.

High levels of poisoning may require hyperbaric oxygen, which should be considered for patients who are unconscious or have an abnormal score on the Carbon Monoxide Neuropsychological Screening Battery, COHb of >40%, signs of cardiac ischemia or arrhythmia, history of ischemic heart disease with COHb level >20%, recurrent symptoms for up to 3 weeks, or symptoms that have not resolved with normobaric oxygen after 4 to 6 hours.9 Any pregnant woman with CO poisoning should receive hyperbaric therapy.10