A model for evaluating apps

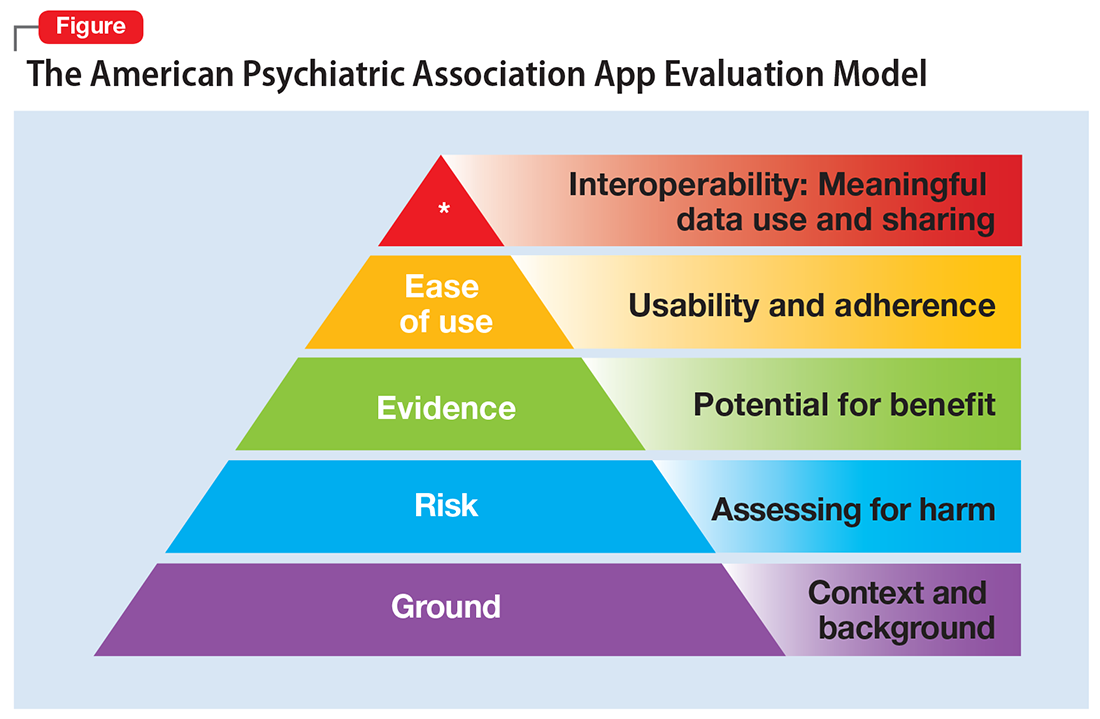

One possible solution is a risk-based and personalized assessment approach to evaluating mental health apps. Although it does not offer scoring or recommendations of specific apps, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) App Evaluation Model (Figure) provides a framework to guide discussion and informed decision-making about apps. (The authors of this article helped create this model, but receive no compensation for that volunteer work.) The pyramid shape reflects the hierarchical nature of the model. To begin the process, start at the base of the pyramid and work upward.

Ground. First, consider the context of the app by determining basic facts, such as who made it, how much it costs, and its technology requirements. This ground layer establishes the credibility of the app’s creator by questioning his or her reputation, ability to update the app, and funding sources. Understanding the app’s business model also will help you determine whether the app will stand the test of time: Will it continue to exist next month or next year, or will a lack of reliable funding lead the vendor to abandon it?

Risk. The next layer assesses the risk, privacy, and security features of the app. Many mental health apps actively aim to avoid falling under the jurisdiction of U.S. federal health care privacy rules, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, so there is no guarantee that sensitive data supplied to an app will be protected. The true cost of a “free” app often is your patient’s personal mental health information, which the app’s developer may accumulate and sell for profit. Thus, it is wise to check the privacy policy to learn where your patient’s data goes. Furthermore, patients and psychiatrists must be vigilant that malware-infected apps can be uploaded to the app store, which can further compromise privacy.16 You may be surprised to learn that many apps lack a privacy policy, which means there are no protections for personal information or safeguards against the misuse of mental health data.17 Checking that an app at least promises to digitally protect mental health data through encryption and secure storage also is a good step.

The goal of considering these factors is not to create a score, but rather to be aware of them and consider them in the context of the specific app, patient, and clinical situation. Doing so helps determine whether the app meets the appropriate risk, privacy, and security standards for your patient.

Evidence. The next layer of the evaluation framework is evidence. The goal is to seek an app with clinical evidence of effectiveness. Simply put, if a patient is going to use an app, he should use one that works. An app without formal evidence may be effective, but it is important to make sure the patient is aware that these claims have not been verified. Many apps claim that they offer cognitive-behavioral therapy or mindfulness therapy, but few deliver on such claims.18 It is wise to try an app before recommending it to a patient to ensure that it does what it claims it does, and does not offer dangerous or harmful recommendations.