Treatment: Medication, psychotherapy, or both

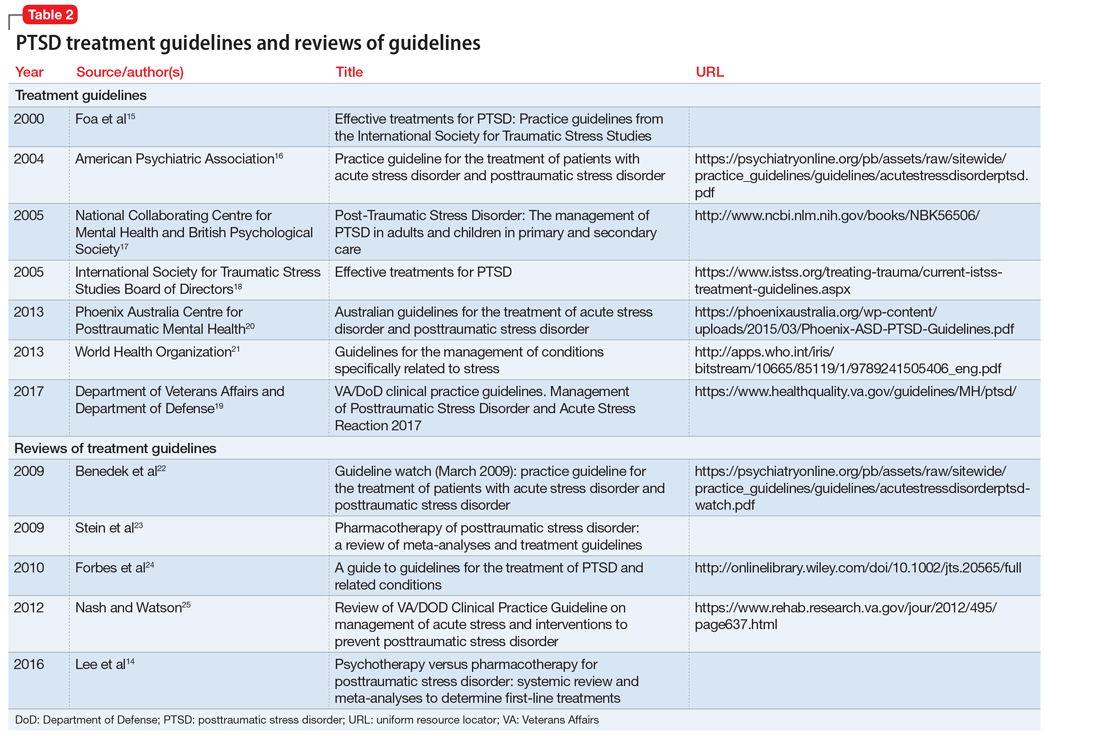

Both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy—as monotherapy or in combination—are beneficial for treatment of PTSD. Research has not conclusively shown either treatment modality to be superior, because adequate head-to-head trials have not been conducted.4 Therefore, the choice of initial treatment is based on individual circumstances, such as patient preference for medication and/or psychotherapy, or the availability of therapists trained in evidence-based PTSD psychotherapy. Pharmacotherapeutic approaches are considered especially beneficial for depressive- and anxiety-like symptoms of PTSD, and trauma-focused psychotherapies are presumed to address the neuropathology of conditioned fear and anxiety responses involved in PTSD.14 Table 214-25 provides a list of published treatment guidelines and reviews to help clinicians seeking further detail beyond that provided in this article.

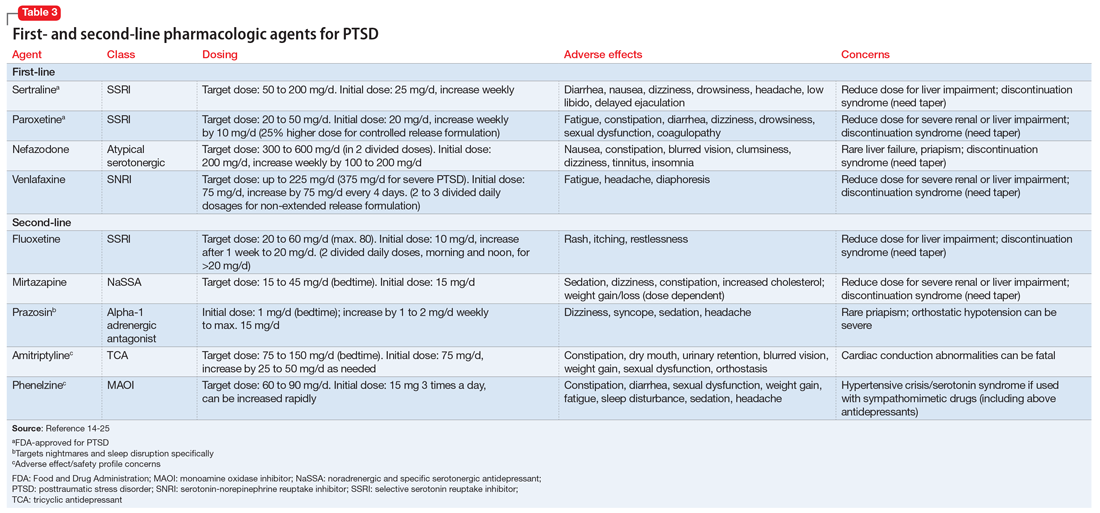

Antidepressants are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for PTSD. These medications are effective for treating major depressive disorder, and have beneficial properties for PTSD independent of their antidepressant effects. The serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for the treatment of PTSD.6 Other recommended medications include the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine, and nefazodone, an atypical serotoninergic agent.13 Other antidepressants with less published evidence of effectiveness are used as second-line pharmacotherapies for PTSD, including fluoxetine (SSRI), and mirtazapine, a noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA).4 Older medications, such as the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline and the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine, have also been used successfully as second-line treatments, but evidence of their benefit is less convincing than that supporting the first-line SSRIs/SNRIs. Additionally, their less favorable adverse effect and safety profiles make them less attractive treatment choices.13 Table 314-25 provides a list of first- and second-line medications for PTSD with recommended dosages and adverse effect profiles.

Other medications. Antiepileptics, antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines have not been demonstrated to have efficacy for primary treatment of PTSD, and none of the medications are considered first-line treatments, although sometimes they are used adjunctively in attempts to enhance the effectiveness of antidepressants. Benzodiazepines are sometimes used to target symptoms, such as sleep disturbance or hyperarousal, but only for very short periods. Several authoritative reviews strongly recommend against practices of polypharmacy that commonly involves use of these agents.4,14 Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist, has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for nightmares and sleep disturbances, and has grown increasingly popular for treating these symptoms in PTSD, especially in military veterans.13

A well-established barrier to effective pharmacotherapy of PTSD is medication nonadherence.13 Two common underlying sources of nonadherence are inconsistency with the patient’s treatment preference and intolerable adverse effects. Because SSRIs/SNRIs require 8 to 12 weeks of adequate dosing for symptom relief,13 medication adherence is vital. Explaining to patients that it takes many weeks of consistent dosing for clinical effects and reassuring them that the antidepressant agents used to treat PTSD are not habit-forming may help improve adherence.4

Psychotherapy. Prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy—both trauma-focused therapies—have the best empirical evidence for efficacy for PTSD.4,14,26 Some patients are too anxious or avoidant to participate in trauma-focused psychotherapy and may benefit from a course of antidepressant treatment before initiating psychotherapy to reduce hyperarousal and avoidance symptoms enough to allow them to tolerate therapy that incorporates trauma memories.6 However, current PTSD treatment guidelines no longer recommend stabilization with medication or preparatory therapy as a routine prerequisite to trauma-focused psychotherapy.4

Continue to: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy...