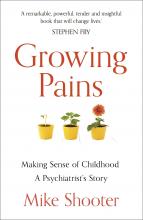

You might be surprised by child psychiatrist’s Mike Shooter’s response revealed in his book, “Growing Pains: Making Sense of Childhood: A Psychiatrist’s Story”(London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2018). Rather than hospitalizing this patient, as was done many times before, he makes a bold decision to listen to the group members, who help the patient develop a plan that ultimately leads to greater resiliency.

Dr. Shooter shares many stories about the power of therapy to heal, often visiting patients at their homes to better understand the dynamics of their distress. Stories themselves heal: “It is the job of the therapist to encourage them to reveal their story, to listen to it, and to help them find a better outcome.”

From these stories, we learn about Dr. Shooter’s passion and commitment to his relationship with the child – listening, fostering autonomy, recognizing the power of family systems, working with a multidisciplinary team, and using his own experiences with depression to better help his patients.

Dr. Shooter closes the distance between himself and readers by sharing his own story – his difficult relationship with his strict father, his own uncertainty about his future profession, the deep depression that could have derailed his family life and career, and the treatment that got him back on track.

This book is an excellent read for psychiatrists and other mental health professionals, whether they work with children or adults. It is especially valuable to psychiatrists like me who work with college students – transitional-age youth at the border between childhood and adulthood. Dr. Shooter beautifully describes the societal ills that have contributed to a global rise in child and adolescent mental health problems:

“We live in an ever-more competitive world. To the normal pressures of growing up are added the educational demands to pass more and more exams, a gloominess about the future, and a loss of faith in political processes to put it right; private catastrophes at home and global catastrophes beamed in from all over the world; and a media that’s in love with how to be popular, how to look attractive, and how to be a success.”

The general public would also find this book an interesting glimpse into the world of child psychiatry. The public as well as politicians would benefit from knowing the value child psychiatry can provide at a time when services are underfunded in many countries, including the United States.

This book uses the words of children to highlight the challenges young people face – from bereavement to bullying to abuse. He writes about children on the “margins of margins.” As I read the book, Dr. Shooter reminded me of psychiatrist and author Robert Coles, who taught my favorite college class and wrote about children in crisis from the Appalachians to Africa.

Not surprisingly, Dr. Shooter describes spending time with Dr. Coles at a conference on bereavement. He adheres to the advice Dr. Coles offered, which was to “Listen to what the children say, not what the adults say about them. ... Follow what your gut tells you, not your head.”

In addition to listening to the patient and your gut, Dr. Shooter describes offering hope as another essential element to treatment. He describes giving hope to children of parents who die by suicide, as these children often fear they will meet their parents’ fate. “And they need to know, too, that suicide is not inevitable. … Help is ready and available to stop the children and young people ever getting to that state.”

One element of treatment Dr. Shooter minimally addresses is psychopharmacology, and mostly in a negative way. While he acknowledges that some children genuinely do have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or depression, he feels they are overdiagnosed and thus overtreated with medication. I would have liked to hear more about the times he prescribed medication and how it was integrated into comprehensive care that included therapy and lifestyle changes. I would not want parents reading this book to feel badly if they have supported having their child take medication for a mental health disorder.

Dr. Shooter does make the important point that therapy is often left on the sidelines in current medical systems. Therapy can benefit people of all ages as we face our own “growing pains.” He highlights the “opportunity for growth” that challenges provide, and indeed gives us a great sense of hope in our lives and our work as psychiatrists.

Dr. Morris is an associate professor of psychiatry and associate program director for student health psychiatry at the University of Florida, Gainesville. She is the author of “The Campus Cure: A Parent’s Guide to Mental Health and Wellness for College Students” (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield of Lanham, 2018).