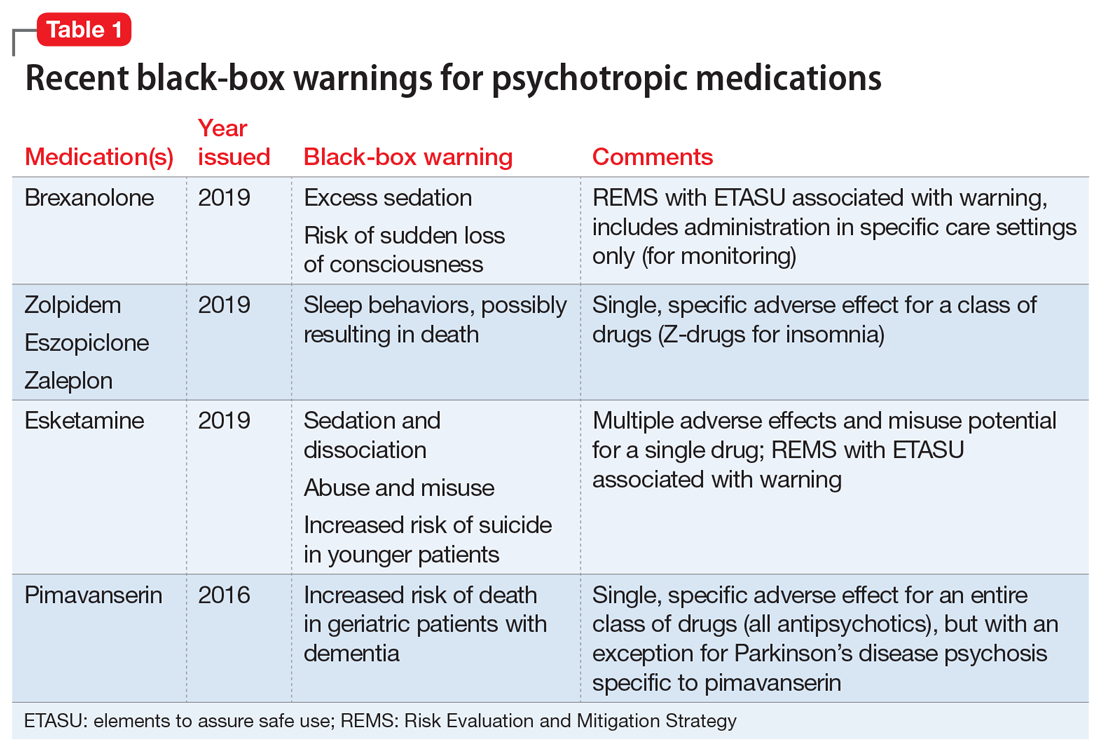

Recently, the FDA issued “black-box” warnings, its most prominent drug safety statements, for esketamine,1 which is indicated for treatment-resistant depression, and the Z-drugs, which are indicated for insomnia2 (Table 1). A black-box warning also comes with brexanolone, which was recently approved for postpartum depression.3 While these newly issued warnings serve as a timely reminder of the importance of black-box warnings, older black-box warnings also cover large areas of psychiatric prescribing, including all medications indicated for treating psychosis or schizophrenia (increased mortality in patients with dementia), and all psychotropic medications with a depression indication (suicidality in younger people).

In this article, we help busy prescribers navigate the landscape of black-box warnings by providing a concise review of how to use them in clinical practice, and where to find information to keep up-to-date.

What are black-box warnings?

A black-box warning is a summary of the potential serious or life-threatening risks of a specific prescription medication. The black-box warning is formatted within a black border found at the top of the manufacturer’s prescribing information document (also known as the package insert or product label). Below the black-box warning, potential risks appear in descending order in sections titled “Contraindications,” “Warnings and Precautions,” and “Adverse Reactions.”4 The FDA issues black-box warnings either during drug development, to take effect upon approval of a new agent, or (more commonly) based on post-marketing safety information,5 which the FDA continuously gathers from reports by patients, clinicians, and industry.6 Federal law mandates the existence of black-box warnings, stating in part that, “special problems, particularly those that may lead to death or serious injury, may be required by the [FDA] to be placed in a prominently displayed box” (21 CFR 201.57(e)).

When is a black-box warning necessary?

The FDA issues a black-box warning based upon its judgment of the seriousness of the adverse effect. However, by definition, these risks do not inherently outweigh the benefits a medication may offer to certain patients. According to the FDA,7 black-box warnings are placed when:

- an adverse reaction so significant exists that this potential negative effect must be considered in risks and benefits when prescribing the medication

- a serious adverse reaction exists that can be prevented, or the risk reduced, by appropriate use of the medication

- the FDA has approved the medication with restrictions to ensure safe use.

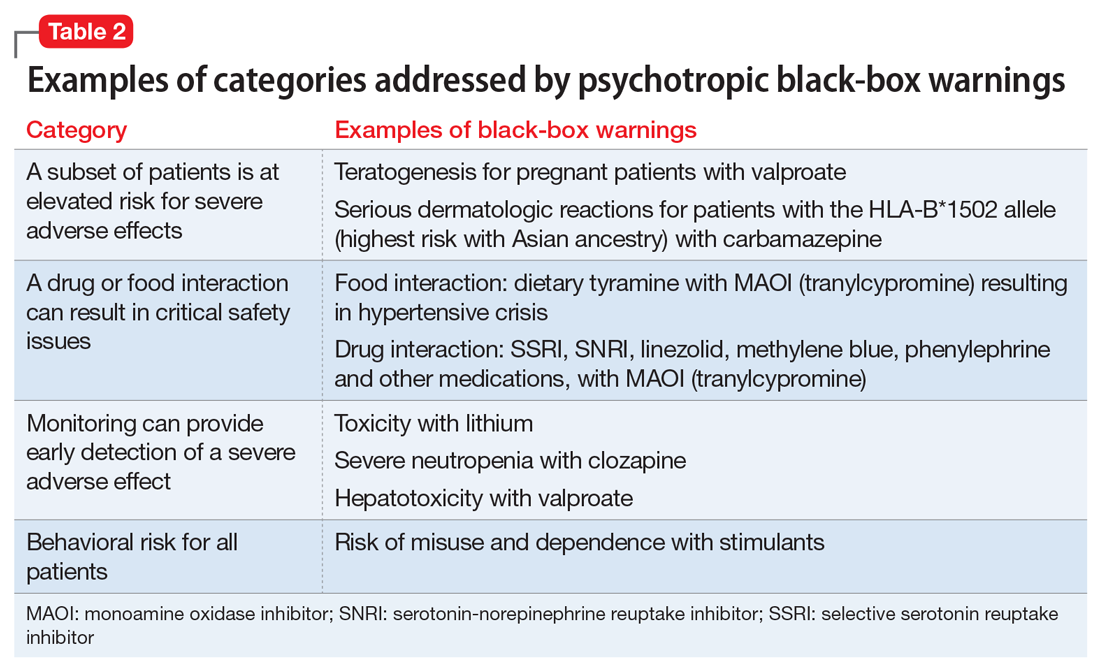

Table 2 shows examples of scenarios where black-box warnings have been issued.8 Black-box warnings may be placed on an individual agent or on an entire class of medications. For example, both antipsychotics and antidepressants have class-wide warnings. Finally, black-box warnings are not static, and their content may change; in a study of black-box warnings issued from 2007 to 2015, 29% were entirely new, 32% were considered major updates to existing black-box warnings, and 40% were minor updates.5

Critiques of black-box warnings focus on the absence of published, formal criteria for instituting such warnings, the lack of a consistent approach in their content, and the infrequent inclusion of any information on the relative size of the risk.9 Suggestions for improvement include offering guidance on how to implement the black-box warnings in a patient-centered, shared decision-making model by adding evidence profiles and implementation guides.10 Less frequently considered, black-box warnings may be discontinued if new evidence demonstrates that the risk is lower than previously appreciated; however, similarly to their placement, no explicit criteria for the removal of black-box warnings have been made public.11

When a medication poses an especially high safety risk, the FDA may require the manufacturer to implement a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program. These programs can describe specific steps to improve medication safety, known as elements to assure safe use (ETASU).4 A familiar example is the clozapine REMS. In order to reduce the risk of severe neutropenia, the clozapine REMS requires prescribers (and pharmacists) to complete specialized training (making up the ETASU). Surprisingly, not every medication with a REMS has a corresponding black-box warning12; more understandably, many medications with black-box warnings do not have an associated REMS, because their risks are evaluated to be manageable by an individual prescriber’s clinical judgment. Most recently, esketamine carries both a black-box warning and a REMS. The black-box warning focuses on adverse effects (Table 1), while the REMS focuses on specific steps used to lessen these risks, including requiring use of a patient enrollment and monitoring form, a fact sheet for patients, and health care setting and pharmacy enrollment forms.13

Continue to: Psychotropic medications and black-box warnings