The authors’ observations

Ms. A’s memory impairment may be secondary to a surgically acquired neurocognitive deficit. In the United States, brain metastases represent a significant public health issue, affecting >100,000 patients per year.5 Metastatic lesions are the most common brain tumors. Lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma are the leading solid tumors to spread to the CNS.5 In cases of single brain metastasis, similar to Ms. A’s solitary left temporal lobe lesion, surgical resection plays a critical role in treatment. It provides histological confirmation of metastatic disease and can relieve mass effect if present. Studies have shown that combined surgical resection with radiation improves survival relative to patients who undergo radiation therapy alone.6,7

However, the benefits of surgical resection need to be balanced with preservation of neurologic function. Emerging evidence suggests that a majority of patients have surgically-acquired cognitive deficits due to damage of normal surrounding tissues, and these deficits are associated with reduced quality of life.8,9 Further, a study examining glioma surgical resections found that patients with left temporal lobe tumors exhibit more frequent and severe neurocognitive decline than patients with right temporal lobe tumors, especially in domains such as verbal memory.8 Ms. A’s memory impairment was persistent during her postoperative course, which suggests that it was not just an immediate post-surgical phenomenon, but a longer-lasting cognitive change directly related to the resection.

It is also possible that Ms. A had a prior neurocognitive disorder that manifested to a greater degree as a result of the CNS tumor. Ms. A might have had early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, although her intact memory before surgery makes this less likely. Alternatively, she could have had vascular dementia, especially given her long-standing hypertension and diabetes. This might have been missed in the initial evaluation because executive function was not tested. However, the relatively abrupt onset of memory problems after surgery suggests that she had no underlying neurocognitive disorder.

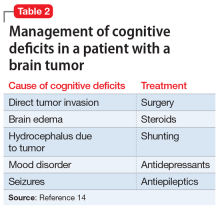

Ms. A’s presumed episode of MDD might also explain her memory changes. Major depressive disorder is increasingly common among geriatric patients, affecting approximately 5% of community-dwelling older adults.10 Its incidence increases with medical comorbidities, as suggested by depression rates of 5% to 10% in the primary care setting vs 37% in patients after critical-care hospitalizations.10 Late-life depression (LLD) occurs in adults age ≥60. Unlike depression in younger patients, LLD is more likely to be associated with cognitive impairment, specifically impairment of executive function and memory.11 The incidence of cognitive impairment in LLD is higher in patients with a history of depression, such as Ms. A.11,12 However, in general, patients who are depressed have memory complaints out of proportion to the clinical findings, and they show poor effort on cognitive testing. Ms. A exhibited neither of these, which makes it less likely that LLD was the exclusive cause of her memory loss.13 Table 214 outlines the management of cognitive deficits in a patient with a brain tumor.

EVALUATION Increasingly agitated and paranoid

After the tumor resection, Ms. A becomes increasingly irritable, uncooperative, and agitated. She repeatedly demands to be discharged. She insists she is fine and refuses medications and further laboratory workup. She becomes paranoid about the nursing staff and believes they are trying to kill her.

Continue to: On psychiatric re-evaluation...