Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is affecting every aspect of medical care. Much has been written about overwhelmed hospital settings, the financial devastation to outpatient treatment centers, and an impending pandemic of mental illness that the existing underfunded and fragmented mental health system would not be prepared to weather. Although COVID-19 has undeniably affected the practice of emergency psychiatry, its impact has been surprising and complex. In this article, I describe the effects COVID-19 has had on our psychiatric emergency service, and how the pandemic has affected me personally.

How the pandemic affected our psychiatric ED

The Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program (CPEP) in Buffalo, New York, is part of the emergency department (ED) in the local county hospital and is staffed by faculty from the Department of Psychiatry at the University at Buffalo. It was developed to provide evaluations of acutely psychiatrically ill individuals, to determine their treatment needs and facilitate access to the appropriate level of care.

Before COVID-19, as the only fully staffed psychiatric emergency service in the region, CPEP would routinely be called upon to serve many functions for which it was not designed. For example, people who had difficulty accessing psychiatric care in the community might come to CPEP expecting treatment for chronic conditions. Additionally, due to systemic deficiencies and limited resources, police and other community agencies refer individuals to CPEP who either have illnesses unrelated to current circumstances or who are not psychiatrically ill but unmanageable because of aggression or otherwise unresolvable social challenges such as homelessness, criminal behavior, poor parenting and other family strains, or general dissatisfaction with life. Parents unable to set limits with bored or defiant children might leave them in CPEP, hoping to transfer the parenting role, just as law enforcement officers who feel impotent to apply meaningful sanctions to non-felonious offenders might bring them to CPEP seeking containment. Labeling these problems as psychiatric emergencies has made it more palatable to leave these individuals in our care. These types of visits have contributed to the substantial growth of CPEP in recent years, in terms of annual patient visits, number of children abandoned and their lengths of stay in the CPEP, among other metrics.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an emergency psychiatry service that is expected to be all things to all people has been interesting. For the first few weeks of the societal shutdown, the patient flow was unchanged. However, during this time, the usual overcrowding created a feeling of vulnerability to contagion that sparked an urgency to minimize the census. Superhuman efforts were fueled by an unspoken sense of impending doom, and wait times dropped from approximately 17 hours to 3 or 4 hours. This state of hypervigilance was impossible to sustain indefinitely, and inevitably those efforts were exhausted. As adrenaline waned, the focus turned toward family and self-preservation. Nursing and social work staff began cancelling shifts, as did part-time physicians who contracted services with our department. Others, however, were drawn to join the front-line fight.

Trends in psychiatric ED usage during the pandemic

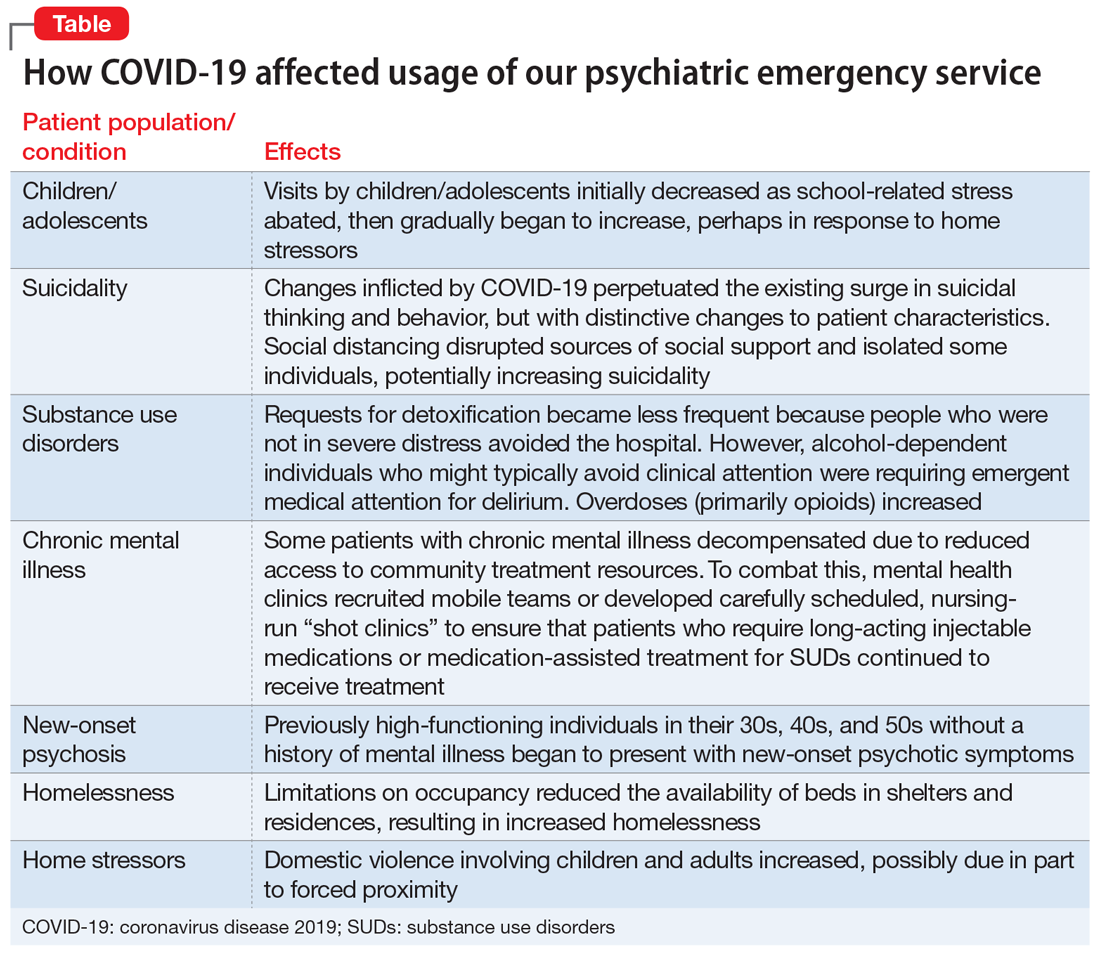

As COVID-19 spread, local media reported the paucity of personal protective equipment (PPE) and created the sense that no one would receive hospital treatment unless they were on the brink of death. Consequently, total visits to the ED began to slow. During April, CPEP saw 25% fewer visits than average. This reduction was partly attributable to cohorting patients with any suspicion of infection in a designated area within the medical ED, with access to remote evaluation by CPEP psychiatrists via telemedicine. In addition, the characteristics and circumstances of patients presenting to CPEP began to change (Table).

Children/adolescents. In the months before COVID-19’s spread to the United States, there had been an exponential surge in child visits to CPEP, with >200 such visits in January 2020. When schools closed on March 13, school-related stress abruptly abated, and during April, child visits dropped to 89. This reduction might have been due in part to increased access to outpatient treatment via telemedicine or telephone appointments. In our affiliated clinics, both new patient visits and remote attendance to appointments by established patients increased substantially, likely contributing to a decreased reliance on the CPEP for treatment. Limited Family Court operations, though, left already-frustrated police without much recourse when called to intervene with adolescent offenders. CPEP once again served an untraditional role, facilitating the removal of these disruptive individuals from potentially dangerous circumstances, under the guise of behavioral emergencies.

Suicidality. While nonemergent visits declined, presentations related to suicidality persisted. In the United States, suicide rates have increased annually for decades. This trend has also been observed locally, with early evidence suggesting that the changes inflicted by COVID-19 perpetuated the surge in suicidal thinking and behavior, but with a change in character. Some of this is likely related to financial stress and social disruption, though job loss seems more likely to result in increased substance use than suicidality. Even more distressing to those coming to CPEP was anxiety about the illness itself, social isolation, and loss. The death of a loved one is painful enough, but disrupting the grief process by preventing people from visiting family members dying in hospitals or gathering for funerals has been devastating. Reports of increased gun sales undoubtedly associated with fears of social decay caused by the pandemic are concerning with regard to patients with suicidality, because shooting has emerged as the means most likely to result in completed suicide.1 The imposition of social distancing directly isolated some individuals, increasing suicidality. Limitations on gathering in groups disrupted other sources of social support as well, such as religious services, clubhouses, and meetings of 12-step programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous. This could increase suicidality, either directly for more vulnerable patients or indirectly by compromising sobriety and thereby adding to the risk for suicide.

Continue to: Substance use disorders (SUDs)