Proposed mechanisms

Although the exact mechanism by which steroids induce psychiatric symptoms is unknown, several mechanisms have been proposed. One hypothesis is that steroid-induced psychopathology is related to decreased levels of corticotropin, norepinephrine, and beta-endorphin immunoreactivity.4,5,7 This may explain why many patients with major depressive disorder have elevated cortisol production and/or lack of suppression of cortisol secretion during a dexamethasone stimulation test, and why approximately one-half of patients with Cushing’s disease experience depressive symptoms.8 This is also likely why antipsychotics, which typically reduce cortisol, are efficacious treatments for some steroid-induced psychiatric symptoms.9

Cognitive impairments from steroid use may be related to these agents’ effects on certain brain regions. One such area is the hippocampus, an important mediator in the creation and maintenance of episodic and declarative memories.5,8,9 Acute glucocorticoid use is associated with decreased activity in the left hippocampus, reduced hippocampal glucose metabolism, and reduced cerebral blood flow in the posterior medial temporal lobe.10 Long-term glucocorticoid exposure is associated with smaller hippocampal volume and lower levels of temporal lobe N-acetylaspartate, a marker of neuronal viability.10 Because working memory depends on the prefrontal cortex and declarative memory relies on the hippocampus, deficits in these functions can be attributed to the effect of prolonged glucocorticoid exposure on glucocorticoid or mineralocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus, reduction of hippocampal volume, or elevated glutamate accumulation in that area.11 In addition, high cortisol levels inhibit brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which plays a crucial role in maintaining neural architecture in key brain regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.11 There is also a correlation between the duration of prednisone treatment and atrophy of the right amygdala, which is an important regulator of mood and anxiety.11 Both the hippocampus and amygdala have dense collections of glucocorticoid receptors. This may explain why patients who receive high-dose corticosteroids can have reversible atrophy in the hypothalamus and amygdala, leading to deficits in emotional learning and the stress response.

Factors that increase risk

Several factors can increase the risk of steroid-induced psychopathology. The most significant is the dose; higher doses are more likely to produce psychiatric symptoms.1,5 Concurrent use of drugs that increase circulating levels of corticosteroids, such as inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme (eg, clarithromycin), also increases the likelihood of developing psychiatric symptoms.1,5 Risk is also increased in patients with liver or renal dysfunction.1 Cerebral spinal fluid/serum albumin ratio, a marker of blood-brain barrier damage, and low serum complement levels were also reported to be independent risk factors,12 with the thought that increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier may allow hydrophobic steroid molecules to more easily penetrate the CNS, leading to increased neuropsychiatric effects. Hypoalbuminemia is another reported risk factor, perhaps because lower levels of serum albumin are related to higher levels of free and active glucocorticoids, which are normally inactive when bound to albumin.13 There also appears to be an increased prevalence of steroid-induced psychopathology in women, perhaps due to greater propensity in women to seek medical care or a higher prevalence of women with medical disorders that are treated with steroids.5 A previous history of psychiatric disorders may not increase risk.5

Several methods for reducing risk have been proposed, including using a divided-dosing regimens that may lower peak steroid plasma concentrations.13,14 However, the best prevention of steroid-induced psychiatric symptoms are awareness, early diagnosis, and intervention. Studies have suggested that N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists15 and other agents that decrease glutamate release (such as phenytoin and lamotrigine16) may help prevent corticosteroid-induced hippocampal volume loss. Lamotrigine has been shown to reduce the amount of atrophy in the amygdala in patients taking corticosteroids.17 Phenytoin has also been reported to reduce the incidence of hypomania associated with corticosteroids, perhaps due to its induction of CYP450 activity and acceleration of steroid clearance.16

Treatment options

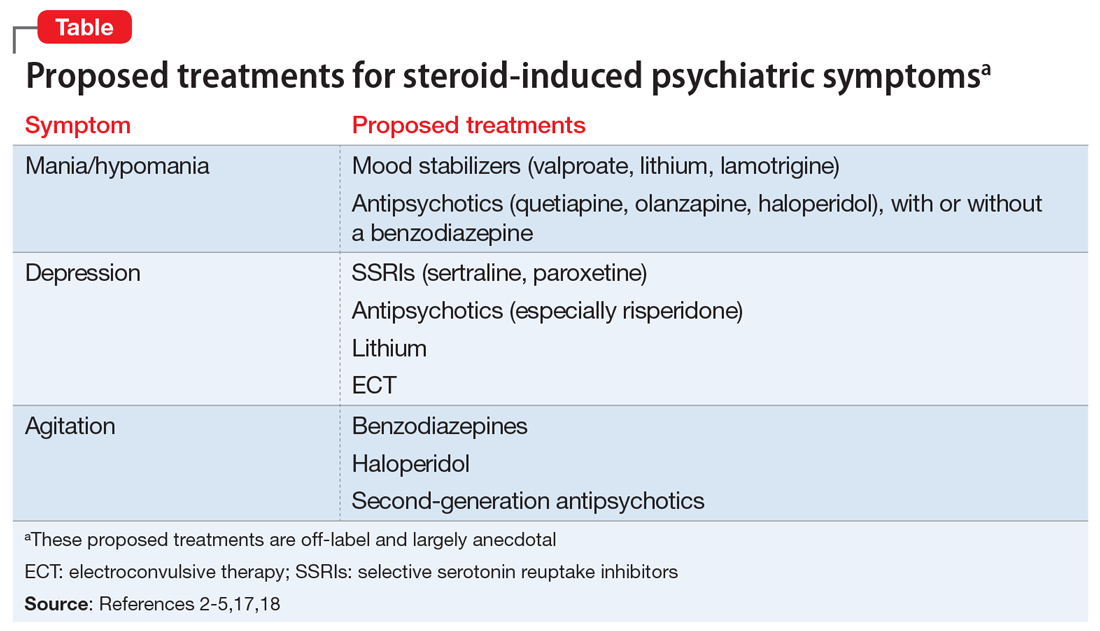

There are no FDA-approved medications for managing steroid-induced psychiatric symptoms.1,16 Treatment is based on evidence from case reports and a few small case series (Table2-5,17,18).

Continue to: When possible, initial treatment...