TREATMENT Bifrontal ECT initiated

On hospital Day 3 Ms. N is administered a trial of IM lorazepam, titrated up to 6 mg/d (maximum tolerated dose) while the treatment team initiates the legal process to conduct ECT because she is unable to give consent. Once Ms. N begins tolerating oral medications, amantadine, 100 mg twice daily, is added to treat her catatonia. As in prior hospitalizations, Ms. N is unresponsive to pharmacotherapy alone for her catatonic symptoms. On hospital Day 8, forced ECT is granted, which is 5 days after the process of filing paperwork was started. Bifrontal ECT is utilized with the following settings: frequency 70 Hz, pulse width 1.5 ms, 100% energy dose, 504 mC. Ms. N does not experience a significant improvement until she receives 10 ECT treatments as part of a 3-times-per-week acute series protocol. The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS) and the KANNER scale are used to monitor her progress. Her initial BFCRS score is 17 and initial KANNER scale, part 2 score is 26.

Ms. N spends a total of 61 days in the hospital, which is significantly longer than her previous hospital admissions on our psychiatric unit; these previous admissions were for treatment of both stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia. This increased length of stay coincides with a significantly longer duration of untreated catatonia. Knowledge of her history of both the stuporous and excited subtypes of catatonia would have allowed for faster diagnosis and treatment.1

The authors’ observations

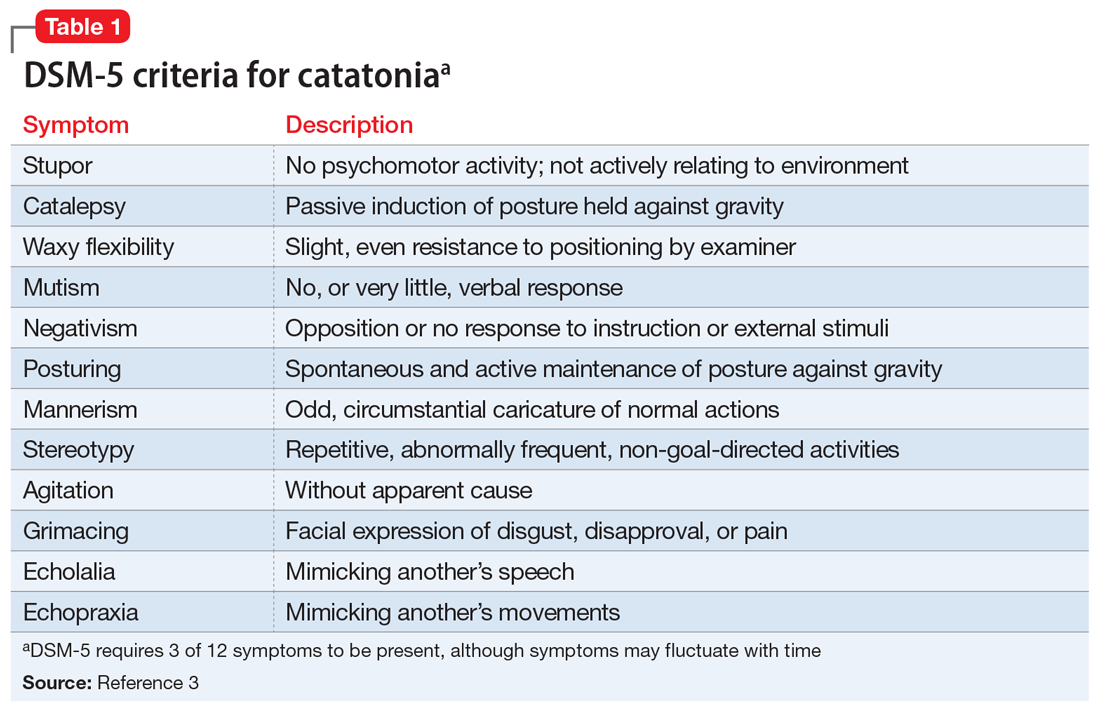

Originally conceptualized as a separate syndrome by Karl Kahlbaum, catatonia was considered only as a specifier for neuropsychiatric conditions (primarily schizophrenia) as recently as DSM-IV-TR.2 DSM-5 describes catatonia as a marked psychomotor disturbance and acknowledges its connection to schizophrenia by keeping it in the same chapter.3 DSM-5 includes separate diagnoses for catatonia, catatonia due to a general medical condition, and unspecified catatonia (for catatonia without a known underlying disorder).3 A recent meta-analysis found the prevalence of catatonia is higher in patients with medical/neurologic illness, bipolar disorder, and autism than in those with schizophrenia.4

Table 13 highlights the DSM-5 criteria for catatonia. DSM-5 requires 3 of 12 symptoms to be present, although symptoms may fluctuate with time.3 If a clinician is not specifically looking for catatonia, it can be a difficult syndrome to diagnose. Does rigidity indicate catatonia, or excessive dopamine blockade from an antipsychotic? How can seemingly contradictory symptoms be part of the same syndrome? Many clinicians associate catatonia with the stuporous subtype (immobility, posturing, catalepsy), which is more prevalent, but the excited subtype, which may involve severe agitation, autonomic dysfunction, and impaired consciousness, can be lethal.2 The diversity in presentation of catatonia is not unlike the challenging variety of symptoms of heart attacks.

A retrospective study of all adults admitted to a hospital found that only 41% of patients who met criteria for catatonia received this diagnosis.5 Further complicating the diagnosis, delirium and catatonia can co-exist; one study found this was the case in 1 of 3 critically ill patients.6 DSM-5 criteria for catatonia due to another medical condition exclude the diagnosis if delirium is present, but this study and others suggest this needs to be reconsidered.3

Continue to: A standardized evaluation is key