Barriers to optimizing program efficacy for both models

Unfortunately, there are stark differences between ALL and severe mental disorders that potentially jeopardize the achievement of these aims, despite the advances in data analytic abilities that drive the learning health system. Specifically, the heterogeneity of psychotic illnesses and the absence of reliable prognostic and modifiable risk markers (responsible for failed efforts to enhance treatment of serious mental illness over the last half century1,2,41) are unlikely to be resolved by a learning health system. These measures are vital to determine whether specific interventions are effective, particularly given the absence of a randomized control group in the EPINET/learning health system design. Fortunately, however, the National Institutes for Health has recently initiated the Accelerating Medicines Partnership–Schizophrenia (AMP-SCZ). This approach seeks “promising biological markers that can help identify those at risk of developing schizophrenia as early as possible, track the progression of symptoms and other outcomes and ultimately define targets for treatment development.”42 The Box1,4,9,10,36,41,43-45 describes some of the challenges involved in identifying biomarkers of severe mental illness.

Box

Biomarkers and modifiable risk factors4,9,10,41,43 are at the core of personalized medicine and its ultimate objective (ie, theragnostics). This is the ability to identify the correct intervention for a disorder based on a biomarker of the illness.10,36 The inability to identify biomarkers of severe mental illness is multifactorial but in part may be attributable to “looking in all the wrong places.”41 By focusing on neural processes that generate psychiatric symptomatology, investigators are assuming they can bridge the “mind gap”1 and specifically distinguish between pathological, compensatory, or collateral measures of poorly characterized limbic neural functions.41

It may be more productive to identify a pathological process within the limbic system that produces a medical condition as well as the mental disorder. If one can isolate the pathologic limbic circuit activity responsible for a medical condition, one may be able to reproduce this in animal models and determine whether analogous processes contribute to the core features of the mental illness. Characterization of the aberrant neural circuit in animal models also could yield targets for future therapies. For example, episodic water intoxication in a discrete subset of patients with schizophrenia44 appears to arise from a stress diathesis produced by anterior hippocampal pathology that disrupts regulation of antidiuretic hormone, oxytocin, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis secretion. These patients also exhibit psychogenic polydipsia that may be a consequence of the same hippocampal pathology that disrupts ventral striatal and lateral hypothalamic circuits. These circuits, in turn, also modulate motivated behaviors and cognitive processes likely relevant to psychosis.45

A strength-based approach

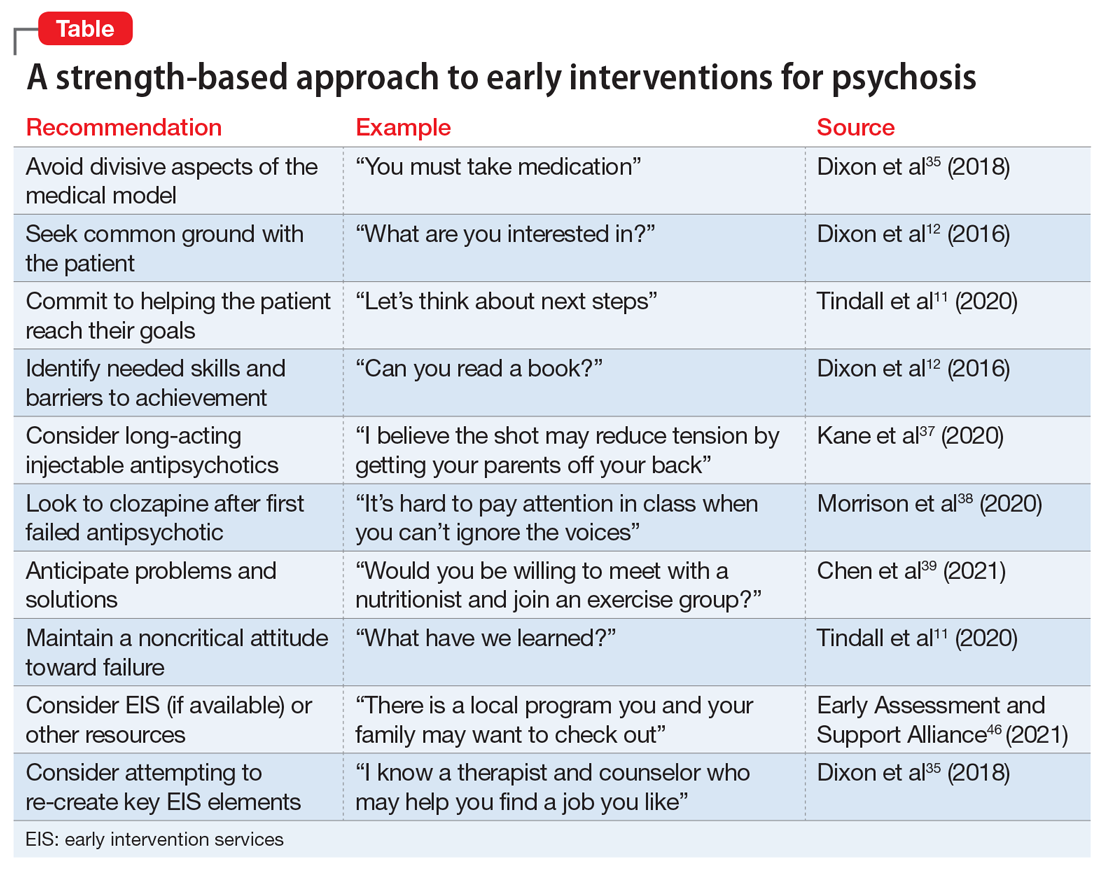

The absence of sufficiently powered RCTs for prevention studies and the reliance on intermediate outcomes for FEP studies leaves unanswered whether such programs can effectively prevent chronic psychosis at a cost society is willing to pay. Still, substantial evidence indicates that outreach, long-acting injectable antipsychotics, early consideration of clozapine, family therapy, CBT for psychosis/attenuated psychosis, and services focused on competitive employment can preserve social and occupational functioning.16,34 Until these broader questions are more definitively addressed, it seems reasonable to apply what we have learned (Table11,12,35,37-39,46).

Simply avoiding the most divisive aspects of the medical model that inadvertently promote stigma and undercut self-confidence may help maintain patients’ willingness to learn how best to apply their strengths and manage their limitations.11 The progression to enduring psychotic features (eg, fixed delusions) may reflect ongoing social isolation and alienation. A strength-based approach seeks first to establish common goals (eg, school, work, friends, family support, housing, leaving home) and then works to empower the patient to successfully reach those goals.35 This typically involves giving them the opportunity to fail, avoiding criticism when they do, and focusing on these experiences as learning opportunities from which success can ultimately result.

It is difficult to offer all these services in a typical private practice setting. Instead, it may make more sense to use one of the hundreds of early intervention services programs in the United States.46 If a psychiatric clinician is dedicated to working with this population, it may also be possible to establish ongoing relationships with primary care physicians, family and CBT therapists, family support services (eg, National Alliance on Mental Illness), caseworkers and employment counselors. In essence, a psychiatrist may be able re-create a multidisciplinary effort by taking advantage of the expertise of these various professionals. The challenge is to create a consistent message for patients and families in the absence of regular meetings with the clinical team, although the recent reliance on and improved sophistication of virtual meetings may help. Psychiatrists often play a critical role even when the patient is not prescribed medication, partly because they are most comfortable handling the risks and may have the most comprehensive understanding of the issues at play. When medications are appropriate and patients with FEP are willing to take them, early consideration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics and clozapine may provide better stabilization and diminish the risk of earlier and more frequent relapses.

Bottom Line

Early interventions for psychosis include the prevention model and the first-episode recovery model. It is difficult to assess, compare, and optimize the effectiveness of such programs. Current evidence supports a ‘strength-based’ approach focused on finding common ground between patients, their support system, and the treatment team.

Related Resources

- Early Assessment and Support Alliance. National Early Psychosis Directory. https://easacommunity.org/nationaldirectory.php

- Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE Early Treatment Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016 ;173(4):362-372

Drug Brand Name

Clozapine • Clozaril