Two years ago, I argued that independent care from nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) would not have ill effects on health outcomes. To the surprise of no one, NPs and PAs embraced the argument; physicians clobbered it.

My case had three pegs: One was that medicine isn’t rocket science and clinicians control a lot less than we think we do. The second peg was that technology levels the playing field of clinical care. High-sensitivity troponin assays, for instance, make missing MI a lot less likely. The third peg was empirical: Studies have found little difference in MD versus non–MD-led care. Looking back, I now see empiricism as the weakest part of the argument because the studies had so many limitations.

I update this viewpoint now because health care is increasingly delivered by NPs and PAs. And there are two concerning trends regarding NP education and experience. First is that nurses are turning to advanced practitioner training earlier in their careers – without gathering much bedside experience. And these training programs are increasingly likely to be online, with minimal hands-on clinical tutoring.

Education and experience pop in my head often. Not every day, but many days I think back to my lucky 7 years in Indiana learning under the supervision of master clinicians – at a time when trainees were allowed the leeway to make decisions ... and mistakes. Then, when I joined private practice, I continued to learn from experienced practitioners.

It would be foolish to argue that training and experience aren’t important.

But here’s the thing:

I will make three points: First, I will bolster two of my old arguments as to why we shouldn’t be worried about non-MD clinicians, then I will propose some ideas to increase confidence in NP and PA care.

Health care does not equal health

On the matter of how much clinicians affect outcomes, a recently published randomized controlled trial performed in India found that subsidizing insurance care led to increased utilization of hospital services but had no significant effect on health outcomes. This follows the RAND and Oregon Health Insurance studies in the United States, which largely reported similar results.

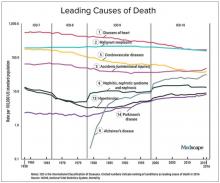

We should also not dismiss the fact that – despite the massive technology gains over the past half-century in digital health and artificial intelligence and increased use of quality measures, new drugs and procedures, and mega-medical centers – the average lifespan of Americans is flat to declining (in most ethnic and racial groups). Worse than no gains in longevity, perhaps, is that death from diseases like dementia and Parkinson’s disease are on the rise.

A neutral Martian would look down and wonder why all this health care hasn’t translated to longer and better lives. The causes of this paradox remain speculative, and are for another column, but the point remains that – on average – more health care is clearly not delivering more health. And if that is true, one may deduce that much of U.S. health care is marginal when it comes to affecting major outcomes.