1. Hales CM, Servais J, Martin CB, et al. Prescription drug use among adults aged 40-79 in the United States and Canada. National Center for Health Statistics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2019. NCHS Data Brief No. 347. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db347.htm

2. Schenker Y, Park SY, Jeong K, et al. Associations between polypharmacy, symptom burden, and quality of life in patients with advanced, life-limiting illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(4):559-566.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anosognosia. 2021. https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Common-with-Mental-Illness/Anosognosia

4. Meyer JM. A concise guide to monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(12):14-16,18-23,47,A.

5. Ban TA. Fifty years chlorpromazine: a historical perspective. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):495-500.

6. Prozac [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2009.

7. Arnold LM, Hess EV, Hudson JI, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose study of fluoxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2002;112(3):191-197.

8. Celexa [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2009.

9. Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, et al. Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(7):682-691.

10. McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Malhotra S, et al. Citalopram in the treatment of binge-eating disorder: a placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(7):807-813.

11. Blank S, Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, et al. Outcomes of late-life anxiety disorders during 32 weeks of citalopram treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):468-472.

12. Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of citalopram in the treatment of late-life anxiety disorders: results from an 8-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(1):146-150.

13. Montgomery SA, Kasper S, Stein DJ, et al. Citalopram 20 mg, 40 mg and 60 mg are all effective and well tolerated compared with placebo in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(2):75-86.

14. Leinonen E, Lepola U, Koponen H, et al. Citalopram controls phobic symptoms in patients with panic disorder: randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000;25(1):24-32.

15. Perna G, Bertani A, Caldirola D, et al. A comparison of citalopram and paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder: a randomized, single-blind study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2001;34(3):85-90.

16. Wikander I, Sundblad C, Andersch B, et al. Citalopram in premenstrual dysphoria: is intermittent treatment during luteal phases more effective than continuous medication throughout the menstrual cycle? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18(5):390-398.

17. English BA, Jewell M, Jewell G, et al. Treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans with citalopram: an open trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(1):84-88.

18. Furmark T, Appel L, Michelgård A, et al. Cerebral blood flow changes after treatment of social phobia with neurokinin-1 antagonist GR205171, citalopram, or placebo. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(2):132-142.

19. Naranjo CA, Poulos CX, Bremner KE, et al. Citalopram decreases desirability, liking, and consumption of alcohol in alcohol-dependent drinkers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;51(6):729-739.

20. Safarinejad MR, Hosseini SY. Safety and efficacy of citalopram in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a double-blind placebo-controlled, fixed dose, randomized study. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18(2):164-169.

21. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204-213.

22. Lexapro [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan USA, Inc; 2016.

23. Guerdjikova AI, McElroy SL, Kotwal R, et al. High-dose escitalopram in the treatment of binge-eating disorder with obesity: a placebo-controlled monotherapy trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(1):1-11.

24. Aigner M, Treasure J, Kaye W, et al. World federation of societies of biological psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for pharmacological treatment of eating disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12:400-443.

25. Fineberg NA, Tonnoir B, Lemming O, et al. Escitalopram prevents relapse of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17(6-7):430-439.

26. Stein DJ, Andersen EW, Tonnoir B, et al. Escitalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, paroxetine-referenced, fixed-dose, 24-week study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(4):701-711.

27. Stahl SM, Gergel I, Li D. Escitalopram in the treatment of panic disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1322-1327.

28. Freeman EW, Sondheimer SJ, Sammel MD, et al. A preliminary study of luteal phase versus symptom-onset dosing with escitalopram for premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(6):769-773.

29. Qi W, Gevonden M, Shalev A. Efficacy and tolerability of high-dose escitalopram in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(1):89-93.

30. Carpenter JS, Guthrie KA, Larson JC, et al. Effect of escitalopram on hot flash interference: a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(6):1399-1404.

31. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267-274.

32. Arnold LM, McElroy SL, Hudson JI, et al. A placebo-controlled, randomized trial of fluoxetine in the treatment of binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(11):1028-1033.

33. Connor KM, Sutherland SM, Tupler LA, et al. Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. Randomized, double-blind study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:17-22.

34. Martenyi F, Brown EB, Zhang H, et al. Fluoxetine versus placebo in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(3):199-206.

35. Davidson JR, Foa EB, Huppert JD, et al. Fluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1005-1013.

36. Kara H, Aydin S, Yücel M, et al. The efficacy of fluoxetine in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Urol. 1996;156(5):1631-1632.

37. Loprinzi CL, Sloan JA, Perez EA, et al. Phase III evaluation of fluoxetine for treatment of hot flashes. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1578-1583.

38. Coleiro B, Marshall SE, Denton CP, et al. Treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40(9):1038-1043.

39. Paxil [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2019.

40. Zhang D, Cheng Y, Wu K, et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Urol. 2019;19(1):2.

41. Walitt B, Urrútia G, Nishishinya MB. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(6):CD011735.

42. Foster CA, Bafaloukos J. Paroxetine in the treatment of chronic daily headache. Headache. 1994;34:587-589.

43. Zylicz Z, Krajnik M, Sorge A, et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of severe non-dermatological pruritus: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(3):1105-1112.

44. Zoloft [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

45. Leombruni P, Pierò A, Lavagnino L, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing sertraline and fluoxetine 6-month treatment in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1599-1605.

46. McElroy SL, Casuto LS, Nelson EB, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of sertraline in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):1004-1006.

47. Milano W, Petrella C, Sabatino C, et al. Treatment of bulimia nervosa with sertraline: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Ther. 2004;21(4):232-237.

48. Brawman-Mintzer O, Knapp RG, Rynn M, et al. Sertraline treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(6):874-881.

49. McMahon CG. Treatment of premature ejaculation with sertraline hydrochloride: a single-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. J Urol. 1998;159(6):1935-1938.

50. Yi ZM, Chen SD, Tang QY, et al. Efficacy and safety of sertraline for the treatment of premature ejaculation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(23):e15989.

51. Uçeyler N, Häuser W, Sommer C. A systematic review on the effectiveness of treatment with antidepressants in fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1279-1298.

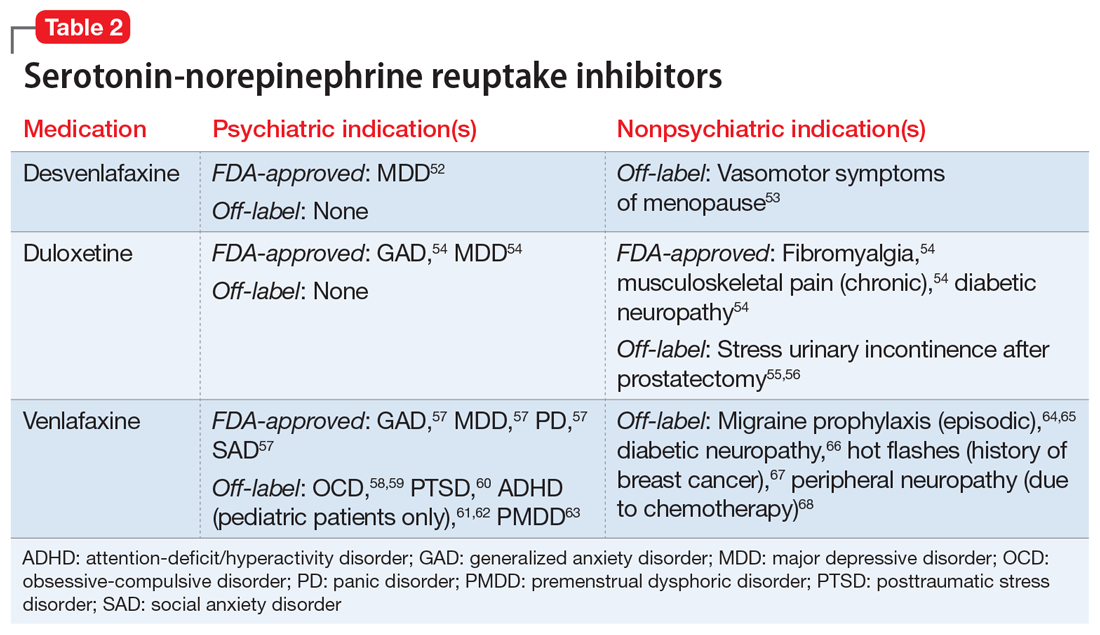

52. Pristiq [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2011.

53. Sun Z, Hao Y, Zhang M. Efficacy and safety of desvenlafaxine treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2013;75(4):255-262.

54. Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2008.

55. Li J, Yang L, Pu C, et al. The role of duloxetine in stress urinary incontinence: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45(3):679-686.

56. Filocamo MT, Li Marzi V, Del Popolo G, et al. Pharmacologic treatment in postprostatectomy stress urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2007;51(6):1559-1564.

57. Effexor XR [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

58. Denys D, Van der Wee N, Van Megen HJ, et al. A double-blind comparison of venlafaxine and paroxetine in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(6):568-575.

59. Albert U, Aguglia E, Maina G, et al. Venlafaxine versus clomipramine in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a preliminary single-blind, 12-week, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(11):1004-1009.

60. Davidson J, Baldwin D, Stein DJ, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder with venlafaxine extended release: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1158-1165.

61. Zarinara AR, Mohammad MR, Hazrati N, et al. Venlafaxine versus methylphenidate in pediatric outpatients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, double-blind comparison trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(7-8):530-535.

62. Mukaddes NM, Abali O. Venlafaxine in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(1):92-95.

63. Cohen LS, Soares CN, Lyster A, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of premenstrual use of venlafaxine (flexible dose) in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(5):540-543.

64. Ozyalcin SN, Talu GK, Kiziltan E, et al. The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache. 2005;45(2):144-152.

65. Tarlaci S. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):254-258.

66. Kadiroglu AK, Sit D, Kayabasi H, et al. The effect of venlafaxine HCl on painful peripheral diabetic neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2008;22(4):241-245.

67. Evans ML, Pritts E, Vittinghoff E, et al. Management of postmenopausal hot flushes with venlafaxine hydrochloride: a randomized, controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):161-166.

68. Farshchian N, Alavi A, Heydarheydari S, et al. Comparative study of the effects of venlafaxine and duloxetine on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2018;82(5):787-793.

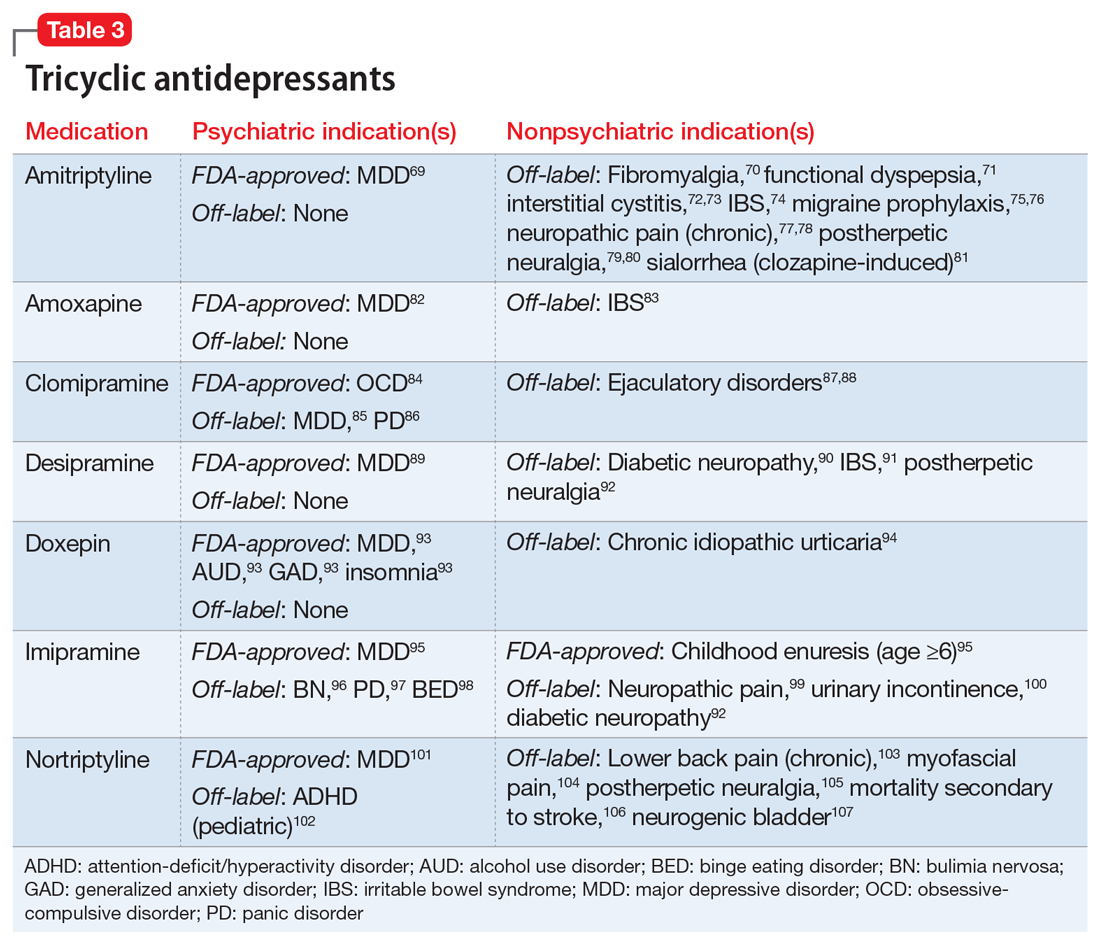

69. Amitriptyline Hydrochloride [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Sandoz Inc; 2014.

70. Hauser W, Wolfe F, Tolle T, et al. The role of antidepressants in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systemic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(4):297-307.

71. Braak B, Klooker T, Lei A, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the effects of amitriptyline on drinking capacity and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia, a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(6):638-648.

72. Van Ophoven A, Pokupic S, Heinecke A, et al. A prospective, randomized, placebo controlled, double-blind study of amitriptyline for the treatment of interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2004;172(2):533-536.

73. Foster HE Jr, Hanno P, Nickel JC, et al; Interstitial Cystitis Collaborative Research Network. Effect of amitriptyline on symptoms in treatment naïve patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2010;183(5):1853-1858.

74. Vahedi H, Merat S, Momtahen S, et al. Clinical trial: the effect of amitriptyline in patients with diarrhoea-predominent irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(8):678-684.

75. Bulut S, Berilgen MS, Baran A, et al. Venlafaxine versus amitriptyline in the prophylactic treatment of migraine: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2004;107(1):44-48.

76. Keskinbora K, Aydinli I. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of topiramate and amitriptyline either alone or in combination for the prevention of migraine. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110(10):979-984.

77. Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, et al. Effects of desipramine, amitriptyline, and fluoxetine on pain in diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(19):1250-1256.

78. Boyle J, Eriksson M, Gribble L, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of amitriptyline, duloxetine, and pregabalin in patients with chronic diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: impact on pain, polysomnographic sleep, daytime functioning, and quality of life. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2451-2458.

79. Graff-Radford SB, Shaw LR, Naliboff BN. Amitriptyline and fluphenazine in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(3):188-192.

80. Watson CP, Evans RJ, Reed K, et al. Amitriptyline versus placebo in postherpetic neuralgia. Neurology. 1982;32(6):671-673.

81. Sinha S, Simlai J, Praharaj SK. Very low dose amitriptyline for clozapine-associated sialorrhea. Curr Drug Saf. 2016;11(3):262-263.

82. Amoxapine [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Watson Pharma, Inc; 2014.

83. Weinberg DS, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ, et al. American Gastroenterological Association institute guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1146-1148.

84. Anafranil (clomipramine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Whitby, Ontario: Patheon Inc; 2012.

85. Clomipramine dose-effect study in patients with depression: clinical end points and pharmacokinetics. Danish University Antidepressant Group (DUAG). Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66(2):152-165.

86. Caillard V, Rouillon F, Viel J, et al. Comparative effects of low and high doses of clomipramine and placebo in panic disorder: a double-blind controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99(1):51-58.

87. Segraves RT, Saran A, Segraves K, et al. Clomipramine versus placebo in the treatment of premature ejaculation: a pilot study. J Sex Marital Therap. 1993;19(3):198-200.

88. Rowland DL, de Gouveia Brazao CA, Koos Slob A. Effective daily treatment with clomipramine in men with premature ejaculation when 25 mg (as required) is ineffective. BJU Int. 2001;87(4):357-360.

89. Norpramin (desipramine hydrochloride) [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; 2014.

90. Max MB, Kishore-Kumar R, Schafer SC, et al. Efficacy of desipramine in painful diabetic neuropathy: a placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 1991;45(1):3-9.

91. Drossman DA, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(1):19-31.

92. Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):162-173.

93. Doxepin hydrochloride [package insert]. Morgantown, WV: Mylan Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2014.

94. Goldsobel AB, Rohr AS, Siegel SC, et al. Efficacy of doxepin in the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78(5 Pt 1):867-873.

95. Imipramine hydrochloride [package insert]. Fairfield, NJ: Excellium Pharmaceutical, Inc; 2012.

96. Pope HG Jr, Hudson JI, Jonas JM, et al. Bulimia treated with imipramine: a placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(5):554-558.

97. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2529-2536.

98. Laederach-Hofmann K, Graf C, Horber F, et al. Imipramine and diet counseling with psychological support in the treatment of obese binge eaters: a randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind study. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26(3):231-244.

99. Sindrup SH, Bach FW, Madsen C, et al. Venlafaxine versus imipramine in painful polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60(8):1284-1289.

100. Lin HH, Sheu BC, Lo MC, et al. Comparison of treatment outcomes of imipramine for female genuine stress incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106(10):1089-1092.

101. Pamelor (nortriptyline) [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Inc; 2007.

102. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. Nortriptyline treatment of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and tic disorder or Tourette’s syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):205-210.

103. Atkinson JH, Slater MA, Williams RA, et al. A placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of nortriptyline for chronic low back pain. Pain. 1998;76(3):287-296.

104. Desai MJ, Saini V, Saini S. Myofacial pain syndrome: a treatment review. Pain Ther. 2013;2(1):21-36.

105. Chandra K, Shafiq N, Pandhi P, et al. Gabapentin versus nortriptyline in post-herpetic neuralgia patients: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial – the GONIP trial. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;44(8):358-363.

106. Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Arndt S, et al. Mortality and poststroke depression: a placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(10):1823-1829.

107. Martin MR, Schiff AA. Fluphenazine/nortriptyline in the irritable bladder syndrome. A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Br J Urol. 1984;56(2):178-179.

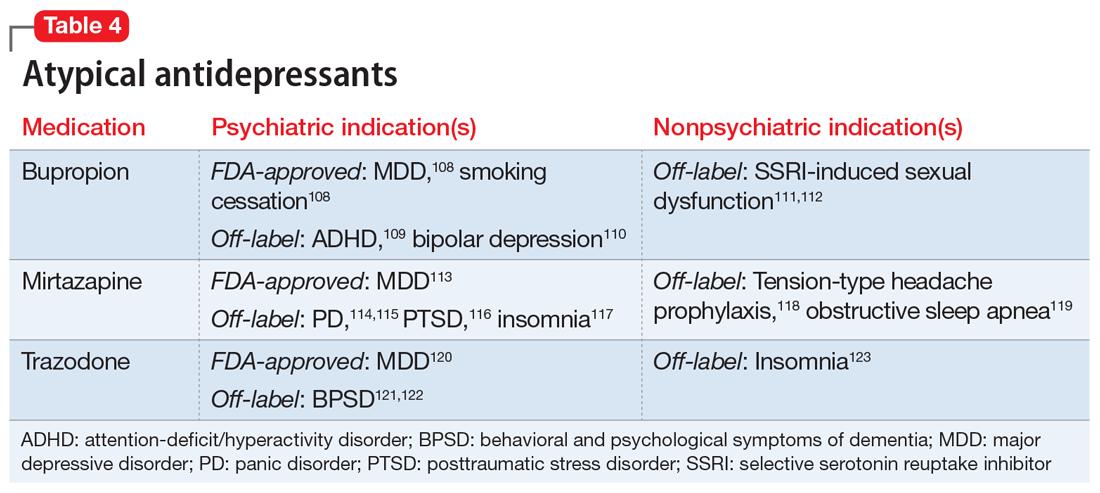

108. Wellbutrin (bupropion hydrochloride) [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2017.

109. Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Srisurapanont M, et al. Bupropion for adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(7):611-617.

110. Li DJ, Tseng PT, Chen YW, et al. Significant treatment effect of bupropion in patients with bipolar disorder but similar phase-shifting rate as other antidepressants: a meta-analysis following the PRISMA guidelines. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(13):e3165.

111. Clayton AH, Warnock JK, Kornstein SG, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion SR as an antidote for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):62-67.

112. Safarinejad MR. Reversal of SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction by adjunctive bupropion in menstruating women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(3):370-378.

113. Remeron (mirtazapine) [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, Inc; 2020.

114. Boshuisen ML, Slaap BR, Vester-Blokland ED, et al. The effect of mirtazapine in panic disorder: an open label pilot study with a single-blind placebo run-in period. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(6):363-368.

115. Sarchiapone M, Amore M, De Risio S, et al. Mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder: an open-label trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(1):35-38.

116. Connor KM, Davidson JR, Weisler RH, et al. A pilot study of mirtazapine in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(1):29-31.

117. Wichniak A, Wierzbicka A, Walecka M, et al. Effects of antidepressants on sleep. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):63.

118. Bedtsen L, Jensen R. Mirtazapine is effective in the prophylactic treatment of chronic tension-type headache. Neurology. 2004;62(10):1706-1711.

119. AbdelFattah MR, Jung SW, Greenspan MA, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea compared to placebo. A systemic review with meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2020;24(2):443-453.

120. Desyrel [package insert]. Locust Valley, NY: Pragma Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2017.

121. Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomized, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-359.

122. Sultzer DL, Gray KF, Gunay I, et al. A double-blind comparison of trazodone and haloperidol for treatment of agitation in patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;5(1):60-69.

123. Yi XY, Ni SF, Ghadami MR, et al. Trazodone for the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2018;45:25-32.

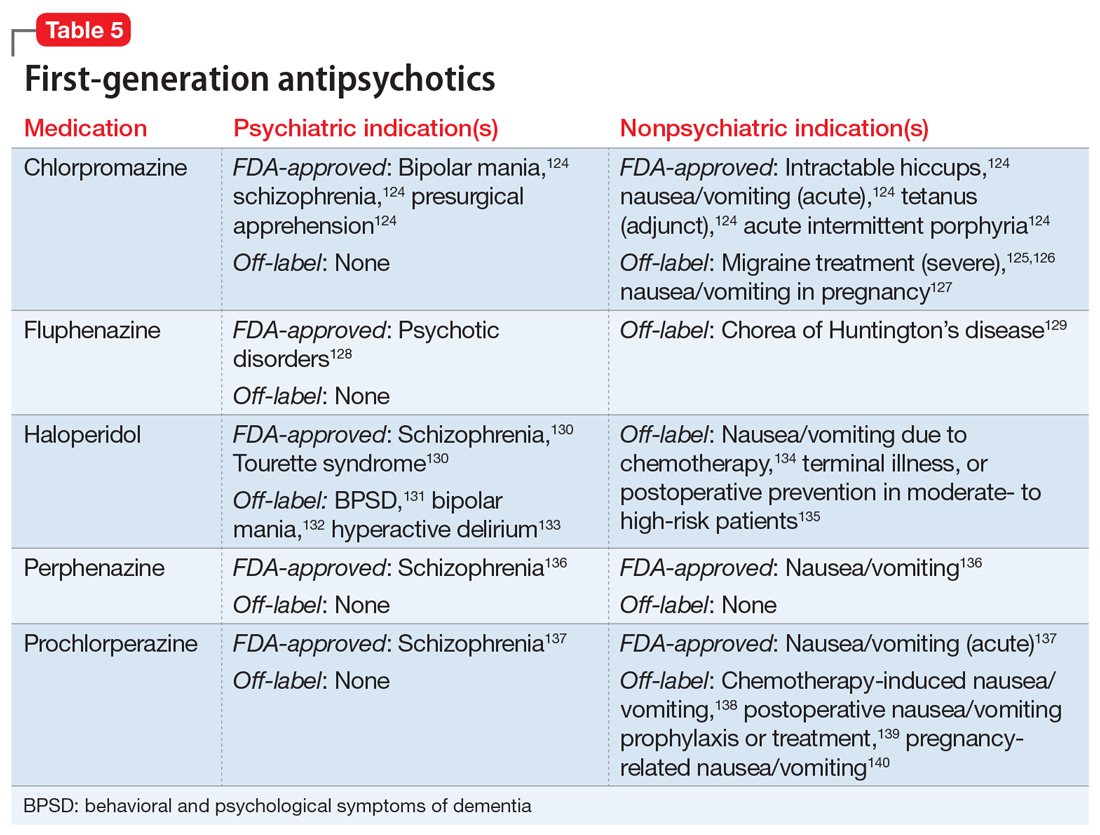

124. Chlorpromazine hydrochloride [package insert]. Minneapolis, MN: Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Inc; 2010.

125. Bigal ME, Bordini CA, Speciali JG. Intravenous chlorpromazine in the emergency department treatment of migraines: a randomized controlled trial. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(2):141-148.

126. Bell R, Montoya D, Shuaib A, et al. A comparative trial of three agents in the treatment of acute migraine headache. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19(10):1079-1082.

127. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 189: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(1):e15-e30.

128. Fluphenazine hydrochloride [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Lannett Company, Inc; 2019.

129. Bonelli RM, Wenning GK. Pharmacological management of Huntington’s disease: an evidence-based review. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(21):2701-2720.

130. Haldol [package insert]. Columbus, OH: American Health Packaging; 2020.

131. MacDonald K, Wilson M, Minassian A, et al. A naturalistic study for intramuscular haloperidol versus intramuscular olanzapine for the management of acute agitation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):317-322.

132. Goikolea JM, Colom F, Capapey J, et al. Faster onset of antimanic action with haloperidol compared to second-generation antipsychotics. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials in acute mania. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(4):305-316.

133. Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, et al. Haloperidol and ziprasidone for treatment of delirium in critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2506-2516.

134. Lohr L. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer J. 2008;14(2):85-93.

135. Büttner M, Walder B, von Elm E, et al. Is low-dose haloperidol a useful antiemetic?: A meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2004;101(6):1454-1463.

136. Perphenazine [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Sandoz Inc; 2010.

137. Compazine [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline; 2004.

138. Hesketh PJ. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2482-2494.

139. Chen JJ, Frame DG, White TJ. Efficacy of ondansetron and prochlorperazine for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after total hip replacement or total knee replacement procedures: a randomized, double-blind, comparative trial. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(19):2124-2128.

140. Campbell K, Rowe H, Azzam H, et al. The management of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(12):1127-1137.

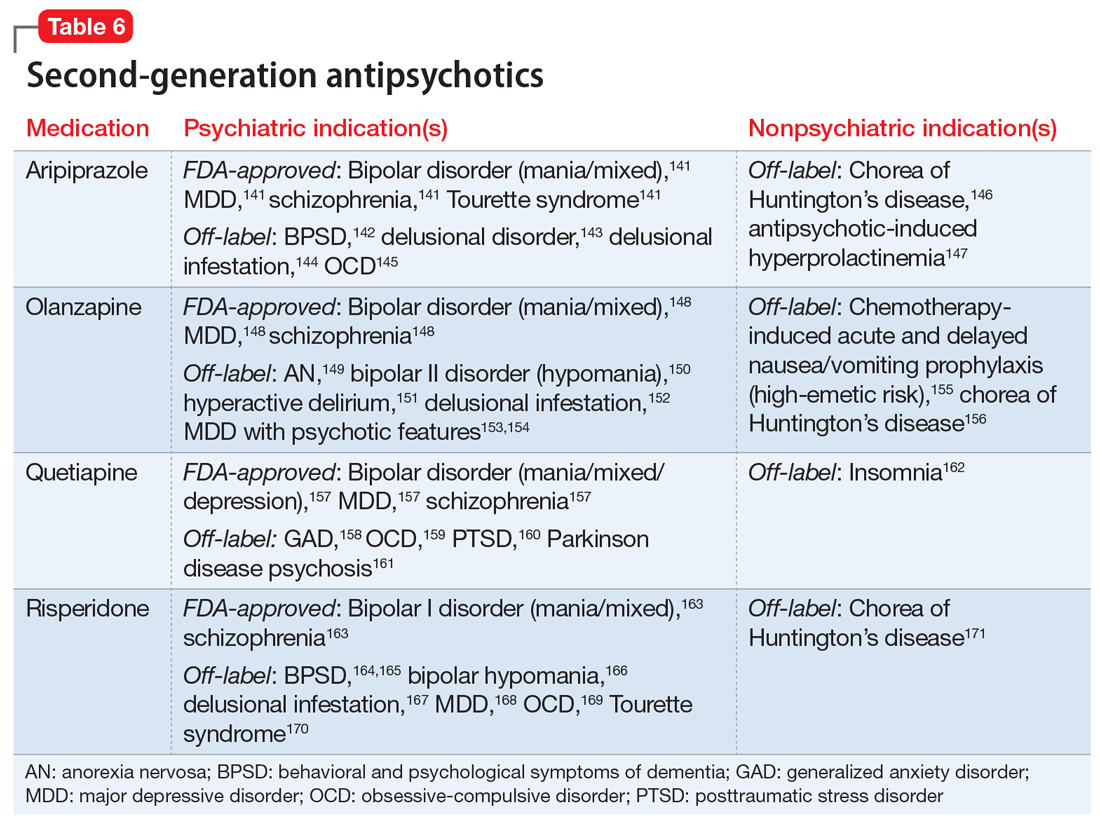

141. Abilify [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc; 2014.

142. Kinon BJ, Stauffer VL, Kollack-Walker S, et al. Olanzapine versus aripiprazole for the treatment of agitation in acutely ill patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(6):601-607.

143. Iannuzzi GL, Patel AA, Stewart JT. Aripiprazole and delusional disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2019;25(2):132-134.

144. Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1428-1434.

145. Sayyah M, Sayyah M, Boostani H, et al. Effects of aripiprazole augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (a double-blind clinical trial). Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):850-854.

146. Lin WC, Chou YH. Aripiprazole effects on psychosis and chorea in a patient with Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1207-1208.

147. Li X, Tang Y, Wang C. Adjunctive aripiprazole versus placebo for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e70179.

148. Zyprexa [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 1997.

149. Attia E, Steinglass JE, Walsh BT, et al. Olanzapine versus placebo in adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):449-456.

150. Dennehy EB, Doyle K, Suppes T. The efficacy of olanzapine monotherapy for acute hypomania or mania in an outpatient setting. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18(3):143-145.

151. Grover S, Kumar V, Chakrabarti S. Comparative efficacy study of haloperidol, olanzapine and risperidone in delirium. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(4):277-281.

152. Bosmans A, Verbanck P. Successful treatment of delusional disorder of the somatic type or “delusional parasitosis” with olanzapine. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2008;41(3):121-122.

153. Meyers BS, Flint AJ, Rothschild AJ, et al; STOP-PD Group. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of olanzapine plus sertraline vs olanzapine plus placebo for psychotic depression: the study of pharmacotherapy of psychotic depression (STOP-PD). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):838-847.

154. Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):365-373.

155. Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized phase III trial. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(5):188-195.

156. Bonelli RM, Mahnert FA, Niederwieser G. Olanzapine for Huntington’s disease: an open label study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2002;25(5):263-265.

157. Seroquel [package insert]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; 2013.

158. Khan A, Atkinson S, Mezhebovsky I, et al. Extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) as adjunctive therapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder and a history of inadequate treatment response: a randomized, double-blind study. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2014;26(1):3-18.

159. Dold M, Aigner M, Lanzenberger R, et al. Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(3):557-574.

160. Villarreal G, Hamner MB, Cañive JM, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(12):1205-1212.

161. Fernandez HH, Friedman JH, Jacques C, et al. Quetiapine for the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1999;14(3):484-487.

162. Doroudgar S, Chou T, Yu J, et al. Evaluation of trazodone and quetiapine for insomnia: an observational study in psychiatric inpatients. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(6):PCC.13m01558. doi: 10.4088/PCC.13m01558

163. Risperdal [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharamceuticals, Inc; 2007.

164. Lim HK, Kim JJ, Pae CU, et al. Comparison of risperidone orodispersible tablet and intramuscular haloperidol in the treatment of acute psychotic agitation: a randomized open, prospective study. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(2):81-86.

165. Currier GW, Chou J, Feifel D, et al. Acute treatment of psychotic agitation: a randomized comparison of oral treatment with risperidone and lorazepam versus intramuscular treatment with haloperidol and lorazepam. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):386-394.

166. Bahk WM, Yoon JS, Kim YH, et al. Risperidone in combination with mood stabilizers for acute mania: a multicentre, open study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(5):299-303.

167. Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(5):500-508.

168. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9): 980-991.

169. McDougle CJ, Epperson CN, Pelton GH, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone addition in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(8):794-801.

170. Scahill L, Leckman JF, Schulz RT, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of risperidone in Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2003;60(7):1130-1135.

171. Dallocchio C, Buffa C, Tinelli C, et al. Effectiveness of risperidone in Huntington Chorea patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(1):101-103.