Despite much progress, major depressive disorder (MDD) continues to be a challenging and life-threatening neuropsychiatric disorder. It is highly prevalent and afflicts tens of millions of Americans.

It is also ranked as the No. 1 disabling medical (not just psychiatric) condition by the World Health Organization.1 A significant proportion of patients with MDD do not respond adequately to several rounds of antidepressant medications,2 and many are labeled as having “treatment-resistant depression” (TRD).

In a previous article, I provocatively proposed that TRD is a myth.3 What I meant is that in a heterogeneous syndrome such as depression, failure to respond to 1, 2, or even 3 antidepressants should not imply TRD, because there is a “right treatment” that has not yet been identified for a given depressed patient. Most of those labeled as TRD have simply not yet received the pharmacotherapy or somatic therapy with the requisite mechanism of action for their variant of depression within a heterogeneous syndrome. IV ketamine, which, astonishingly, often reverses severe TRD of chronic duration within a few hours, is a prime example of why the term TRD is often used prematurely. Ketamine’s mechanism of action (immediate neuroplasticity via glutamate N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonism, and stimulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin [mTOR]) was not recognized for decades because of the obsession with the monoamine model of depression.

Some clinicians may not be aware of the abundance of mechanisms of action currently available for the treatment of MDD as well as bipolar depression. Many practitioners, in both psychiatry and primary care, usually start the treatment of depression with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and if that does not produce a response or remission, they might switch to a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. If that does not control the patient’s depressive symptoms, they start entertaining the notion that the patient may have TRD, not realizing that they have barely scratched the surface of the many therapeutic options and mechanisms of action, one of which could be the “best match” for a given patient.4

There will come a day when “precision psychiatry” finally arrives, and specific biomarkers will be developed to identify the “right” treatment for each patient within the heterogenous syndrome of depression.5 Until that day arrives, the treatment of depression will continue to be a process of trial and error, and hit or miss. But research will eventually discover genetic, neurochemical, neurophysiological, neuroimaging, or neuroimmune biomarkers that will rapidly guide clinicians to the correct treatment. This is critical to avoid inordinate delays in achieving remission and avert the ever-present risk of suicidal behavior.

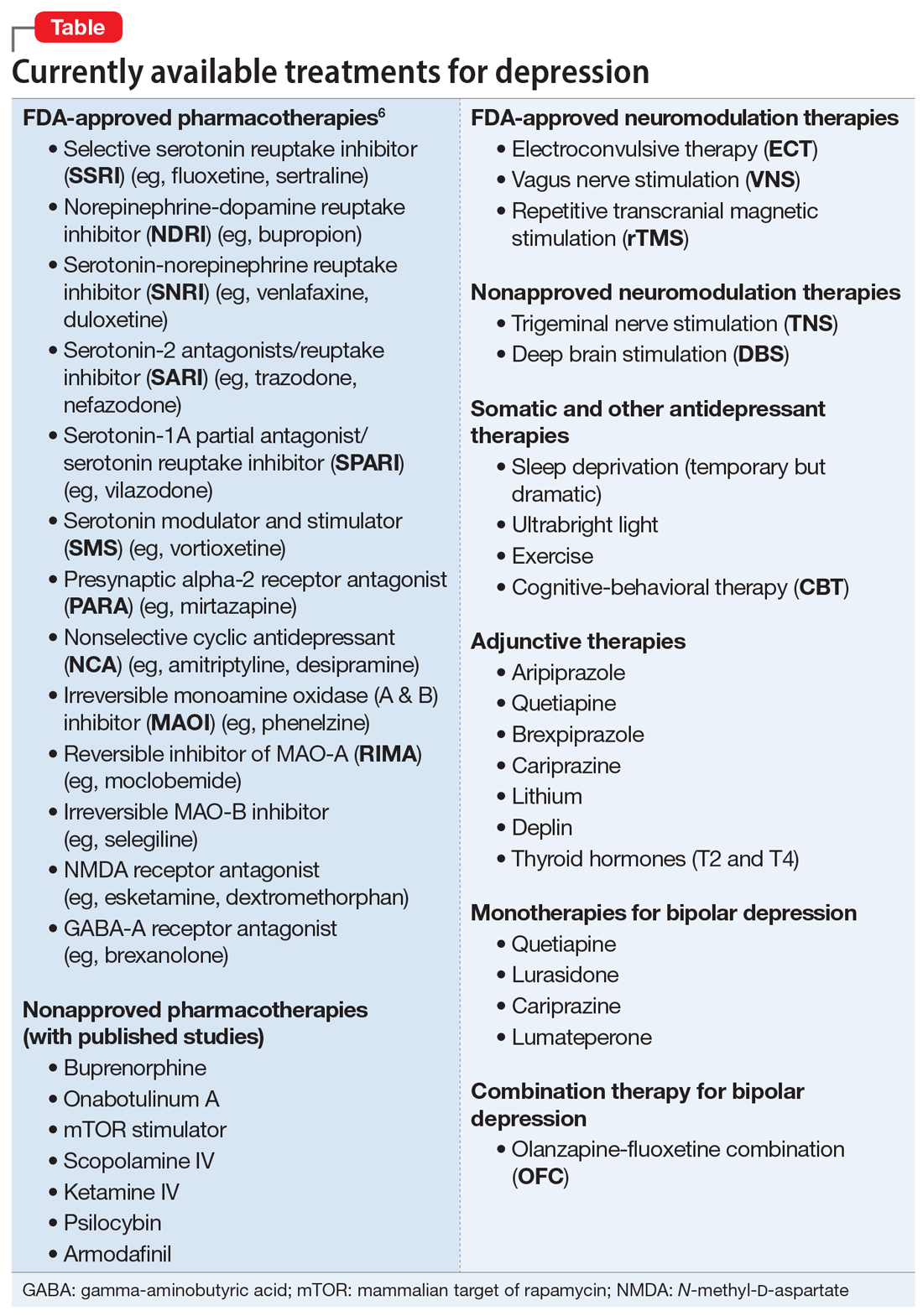

The Table6 provides an overview of the numerous treatments currently available to manage depression. All increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor and restore healthy neuroplasticity and neurogenesis, which are impaired in MDD and currently believed to be a final common pathway for all depression treatments.7

These 41 therapeutic approaches to treating MDD or bipolar depression reflect the heterogeneity of mechanisms of action to address an equally heterogeneous syndrome. This implies that clinicians have a wide array of on-label options to manage patients with depression, aiming for remission, not just a good response, which typically is defined as a ≥50% reduction in total score on one of the validated rating scales used to quantify depression severity, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, or Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia.

Continue to: When several FDA-approved pharmacotherapies...