Mr. D, age 41, presents to the emergency department (ED) with altered mental status and suspected intoxication. His medical history includes alcohol use disorder and spinal injury. Upon initial examination, he is confused, disorganized, and agitated. He receives IM lorazepam 4 mg to manage his agitation. His laboratory workup includes a negative screening for blood alcohol, slightly elevated creatine kinase, and urine toxicology positive for barbiturates and opioids. During re-evaluation by the consulting psychiatrist the following morning, Mr. D is alert, oriented, and calm with an organized thought process. He does not appear to be in withdrawal from any substances and tells the psychiatrist that he takes butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine as needed for migraines. Mr. D says that 3 days before he came to the ED, he also began taking a supplement called phenibut that he purchased online for “well-being and sleep.”

Natural substances have been used throughout history as medicinal agents, sacred substances in religious rituals, and for recreational purposes.1 Supplement use in the United States is prevalent, with 57.6% of adults age ≥20 reporting supplement use in the past 30 days.2 Between 2000 and 2017, US poison control centers recorded a 74.1% increase in calls involving exposure to natural psychoactive substances, mostly driven by cases involving marijuana in adults and adolescents.3 Like synthetic drugs, herbal supplements may have psychoactive properties, including sedative, stimulant, psychedelic, euphoric, or anticholinergic effects. The variety and unregulated nature of supplements makes managing patients who use supplements particularly challenging.

Why patients use supplements

People may use supplements to treat or prevent vitamin deficiencies (eg, vitamin D, iron, calcium). Other reasons may include for promoting wellness in various disease states, for weight loss, for recreational use or misuse, or for overall well-being. In the mental health realm, patients report using supplements to treat depression, anxiety, insomnia, memory, or for vague indications such as “mood support.”4,5

Patients may view supplements as appealing alternatives to prescription medications because they are widely accessible, may be purchased over-the-counter, are inexpensive, and represent a “natural” treatment option.6 For these reasons, they may also falsely perceive supplements as categorically safe.1 People with psychiatric diagnoses may choose such alternative treatments due to a history of adverse effects or treatment failure with traditional psychiatric medications, mistrust of the health care or pharmaceutical industry, or based on the recommendations of others.7

Regulation, safety, and efficacy of dietary supplements

In the US, dietary supplements are regulated more like food products than medications. Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the FDA regulates the quality, safety, and labeling of supplements using Current Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.8 The Federal Trade Commission monitors advertisements and marketing. Despite some regulations, dietary supplements may be adulterated or contaminated, contain unknown or toxic ingredients, have inconsistent potencies, or be sold at toxic doses.9 Importantly, supplements are not required to be evaluated for clinical efficacy. As a result, it is not known if most supplements are effective in treating the conditions for which they are promoted, mainly due to a lack of financial incentive for manufacturers to conduct large, high-quality trials.5

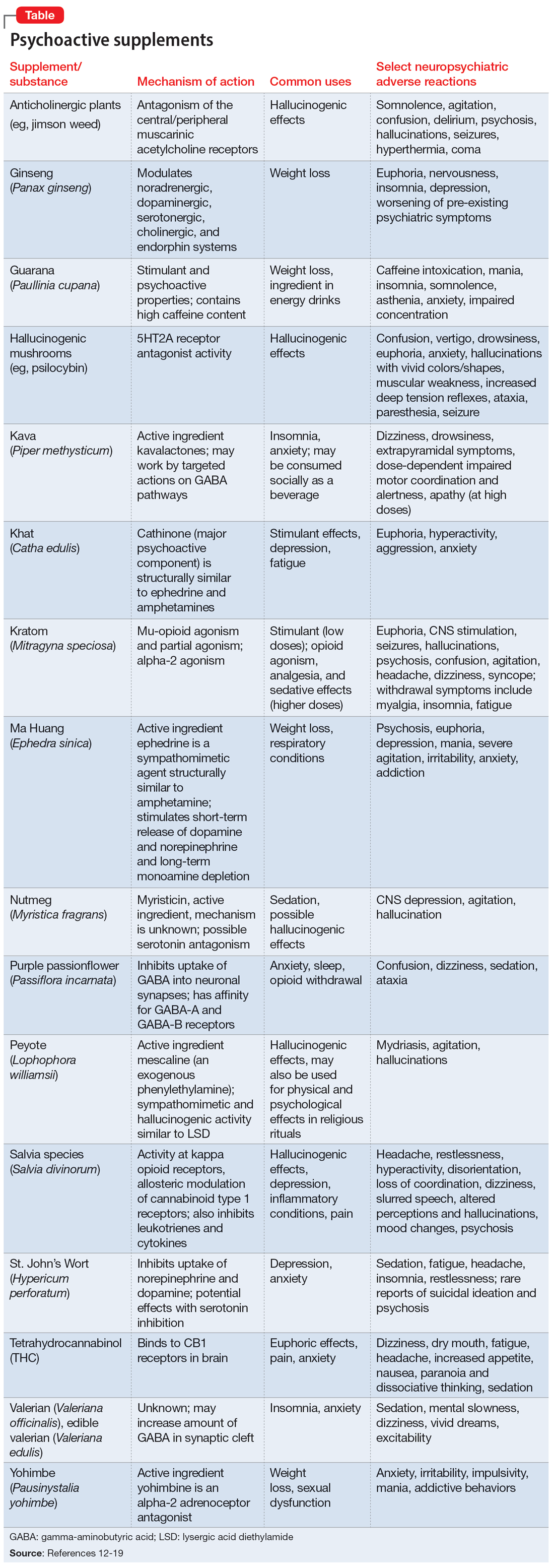

Further complicating matters is the inconsistent labeling of supplements or similar products that are easily obtainable via the internet. These products might be marketed as nutritional supplements or nootropics, which often are referred to as “cognitive enhancers” or “smart drugs.” New psychoactive substances (NPS) are drugs of misuse or abuse developed to imitate illicit drugs or controlled drug substances.10 They are sometimes referred to as “herbal highs” or “legal highs.”11 Supplements may also be labeled as performance- or image-enhancing agents and may include medications marketed to promote weight loss. This includes herbal substances (Table12-19) and medications associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects that may be easily accessible online without a prescription.12,20

The growing popularity of the internet and social media plays an important role in the availability of supplements and nonregulated substances and may contribute to misleading claims of efficacy and safety. While many herbal supplements are available in pharmacies or supplement stores, NPS are usually sold through anonymous, low-risk means either via traditional online vendors or the deep web (parts of the internet that are not indexed via search engines). Strategies to circumvent regulation and legislative control include labeling NPS as research chemicals, fertilizers, incense, bath salts, or other identifiers and marketing them as “not for human consumption.”21 Manufacturers frequently change the chemical structures of NPS, which allows these products to exist within a legal gray area due to the lag time between when a new compound hits the market and when it is categorized as a regulated substance.10

Continue to: Another category of "supplements"...