Ms. A, age 48, is a physician’s assistant with no psychiatric history. She presents to the emergency department (ED) with her partner and daughter due to a 15-minute episode of acute-onset memory loss and concern for stroke. In the ED, Ms. A is confused and repeatedly asks, “Where are we?” “How did we get here?” and “What day is it?” Her partner denies Ms. A has focal neurologic deficits or seizures.

Ms. A had only slept 4 hours the night before she came to the ED because she had just learned that her daughter works in the sex industry. According to her daughter, Ms. A was raped by a soldier many years ago. At that time, her perpetrator told Ms. A that he would kill her entire family if she ever told anyone. As a result, she never pursued any psychological or psychiatric treatment.

During the evaluation, Ms. A shares details regarding her social and medical history; however, she does not recall receiving bad news the night before. She asks the interviewer several times how she got to the hospital, and when a cranial nerve exam is performed, she states, “I am not the patient!”

Ms. A’s vital signs and physical exam are unremarkable. Urinalysis is significant for a ketones level of 20 mmol/L (reference range: negative for ketones), and a urine human chorionic gonadotropin test is negative. A neurologic exam does not identify any focal deficits. No imaging is performed.

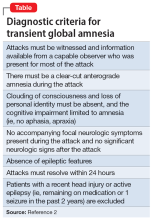

Transient global amnesia (TGA) describes an episode of anterograde, and possibly retrograde, amnesia that lasts up to 24 hours. On presentation, patients experiencing TGA repeatedly ask, “Where am I?” “What day is it?” and “How did I get here?” However, semantic memory—such as knowledge of the world and autobiographical information—is preserved.1 The first case of TGA was described in 1956, and its diagnostic criteria were most recently modified in 1990 (Table2).

Though TGA is the most common cause of acute-onset amnesia, it is rare, affecting approximately 3 to 10 individuals per 100,000. The average age of onset is 61 to 63, with most cases occurring after age 50. TGA is generally thought to affect males and females equally, though some studies suggest a female predominance.3 In most cases (approximately 90%), there is a precipitating event such as physical or emotional stress, change in temperature, or sexual intercourse.4

In this article, we provide an overview of the classification, presentation, differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment of TGA. While TGA is a neurologic diagnosis, in a subset of patients it can present with psychiatric features resembling conversion disorder. For such patients, we argue that TGA can be considered a neuropsychiatric condition (Box 15-12). This classification may empower emergency psychiatry clinicians and psychotherapists to identify and treat the condition, which is not described by the current psychiatric diagnostic system.

Box 1

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a neurologic diagnosis. However, in 1956, Bender8 associated the clinical picture of TGA with psychogenic etiology, 2 years before the term was coined. The same year, Courjon et al9 classified TGA as a functional disorder.

As recent literature on TGA has focused on the neuropsychologic mechanism of memory loss, examination of the condition from a psychodynamic standpoint has fallen out of favor. In fact, the earliest discussions of the condition attributed the absence of TGA from literature prior to the 1950s “to erroneous classification of TGA as psychogenic or hysterical amnesia.”10 However, to refer to this condition as purely neurologic—and without any “psychogenic” or functional features— would be reductive.

In a 2019 case report, Espiridion et al6 considered TGA within the same diagnostic realm as—if not actually a form of—dissociative amnesia (DA). They published the case of a 60-year-old woman with a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who experienced an episode of TGA that had manifested as anterograde and retrograde amnesia for 2 days and was precipitated by a psychotherapy session in which she discussed an individual who had assaulted her 5 years earlier. Much like in the case of Ms. A, the report from Espiridion et al6 clearly exemplifies a psychiatric etiology that shares similar context of a stressor unveiling a past memory too unbearable to maintain in consciousness. They concluded that “this case demonstrates anterograde and identity memory impairments likely induced by her PTSD. It is … possible that this presentation may be labeled PTSD-related dissociative amnesia.”6

Considering TGA as a type of DA within a subset of patients represents progression with regards to considering it as a psychiatric disorder. However, a prominent factor distinguishing TGA from DA is that the latter is more commonly associated with loss of personal identity.5 In TGA, memory of autobiographical information typically is preserved.7

Others have argued for a subtype of “emotional arousal–induced TGA”11 or “emotional TGA.”10 We suggest that this “emotional” subtype of TGA, which clearly was affecting Ms. A, shares similarities with functional neurologic symptom disorder, otherwise known as conversion disorder. The psychoanalytic concept that unconscious psychic distress can be “converted” into a neurologic problem is exemplified by Ms. A. Of note, being female and having an emotional stressor are risk factors for conversion disorder. Additionally, migraine— which was not part of Ms. A’s history—is also a risk factor for both TGA and conversion disorder.12 Despite these similarities, however, TGA’s neurophysiological changes on MRI and self-resolving nature still position the disorder as uniquely neuropsychiatric in the term’s purest sense.

Continue to: Differential diagnosis and workup