Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder that begins in childhood and continues into adulthood. The clinical presentation is characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity that causes functional interference.1 ADHD affects patients’ interpersonal and professional lives as well as their daily functioning.2 Adults with ADHD may suffer from excessive self-criticism, low self-esteem, and sensitivity to criticism.3 The overall prevalence of adult ADHD is 4.4%.4 ADHD in adults is frequently associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders.5 The diagnosis of ADHD in adults requires the presence of ≥5 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity that persist for ≥6 months. Patients must have first had such symptoms before age 12; symptoms need to be present in ≥2 settings and interfere with functioning.1

Treatment of ADHD includes pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. For most patients, pharmacotherapy—specifically stimulant medications—is advised as first-line treatment,6 with adequate trials of methylphenidate and amphetamines before using second-line agents such as nonstimulants. However, despite these medications’ efficacy in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), adherence is low.7 This could be due to inadequate response or adverse effects.8 Guidelines also recommend the use of nonpharmacologic interventions for adults who cannot adhere to or tolerate medication or have an inadequate response.6 Potential nonpharmacologic interventions include transcranial direct current stimulation, mindfulness, psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and chronotherapy.

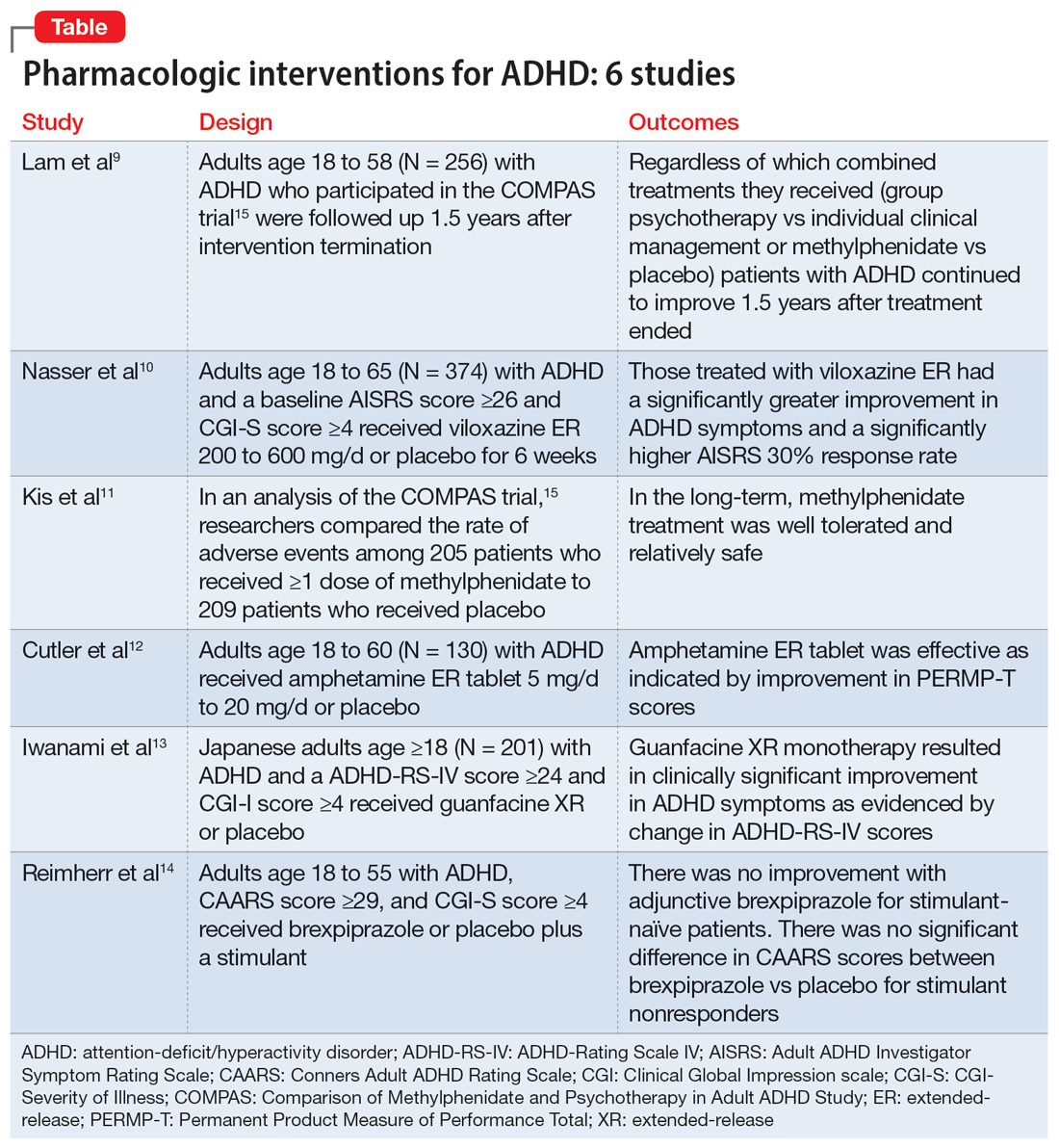

In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we review 6 RCTs of pharmacologic interventions for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years (Table9-14). Part 2 will review nonpharmacologic treatments.

1. Lam AP, Matthies S, Graf E, et al; Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) Consortium. Long-term effects of multimodal treatment on adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: follow-up analysis of the COMPAS Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194980. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4980

The Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) was a multicenter prospective, randomized trial of adults age 18 to 58 with ADHD.15 It compared cognitive-behavioral group psychotherapy (GPT) with individual clinical management (CM), and methylphenidate with placebo. When used in conjunction with methylphenidate, psychological treatments produced better results than placebo. However, studies on the long-term effects of multimodal treatment in ADHD are limited. Lam et al9 performed a follow-up analysis of the COMPAS trial.

Study design

- This observer-masked study involved a follow-up of participants in COMPAS 1.5 years after the interventions were terminated. Of the 433 adults with ADHD who participated in COMPAS, 256 participated in this follow-up.

- The inclusion criteria of COMPAS were age 18 to 58; diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV criteria; chronic course of ADHD symptoms from childhood to adulthood; a Wender Utah Rating Scale short version score ≥30; and no pathological abnormality detected on physical examination.

- The exclusion criteria were having an IQ <85; schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, suicidal or self-injurious behavior, autism, motor tics, or Tourette syndrome; substance abuse/dependence within 6 months prior to screening; positive drug screening; neurologic diseases, seizures, glaucoma, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, uncontrolled arterial hypertension, angina pectoris, tachycardia arrhythmia, or arterial occlusive disease; previous stroke; current bulimia or anorexia; low weight (body mass index [BMI] <20; pregnancy (current or planned) or breastfeeding; treatment with stimulants or ADHD-specific psychotherapy in the past 6 months; methylphenidate intolerance; treatment with antidepressants, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, antipsychotics, theophylline, amantadine, anticoagulants derived from coumarin, antacids, or alpha-adrenergic agonists in the 2 weeks prior to baseline; and treatment with fluoxetine or monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the 4 weeks prior to baseline.

- The primary outcome was a change from baseline on the ADHD Index of Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) score. Secondary outcomes were self-ratings on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and observer-masked ratings of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale and other ADHD rating scale scores, such as the Diagnostic Checklist for the diagnosis of ADHD in adults (ADHD-DC) and subscales of the CAARS.

- COMPAS was open regarding patient and therapist assignment to GPT and CM, but double-masked regarding medication. The statistical analysis focused on the 2x2 comparison of GPT vs CM and methylphenidate vs placebo.

Outcomes

- A total of 251 participants had an assessment with the observer-masked CAARS score. The baseline mean (SD) age was 36.3 (10.1), and approximately one-half (49.8%) of participants were male.

- Overall, 9.2% of patients took methylphenidate >31 days from termination of COMPAS before this study but not at the start of this study. Approximately one-third (31.1%) of patients were taking methylphenidate at follow-up. The mean (SD) daily dosage of methylphenidate was 36 (24.77) mg and 0.46 (0.27) mg/kg of body weight.

- The baseline all-group mean ADHD Index of CAARS score was 20.6. At follow-up, it was 14.7 for the CM arm and 14.2 for the GPT arm (difference not significant, P = .48). The mean score decreased to 13.8 for the methylphenidate arm and to 15.2 for the placebo (significant difference, P = .04).

- Overall, methylphenidate was associated with greater improvement in symptoms than placebo. Patients in the GPT arm had fewer severe symptoms as assessed by the self-reported ADHD Symptoms Total Score compared to the CM arm (P = .04).

- There were no significant differences in self-rating CAARS and observer-rated CAARS subscale scores. Compared to CM, GPT significantly decreased pure hyperactive symptoms on the ADHD-DC (P = .08). No significant differences were observed in BDI scores. The difference between GPT and CM remained significant at follow-up in terms of the CGI evaluation of efficacy (P = .04).

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations