CASE A difficult withdrawal

Three days after he stops drinking alcohol, Mr. G, age 49, presents to a detoxification center with his wife, who drove him there because she was concerned about his condition. She says her husband had been drinking alcohol every night for as long as she can remember. Despite numerous admissions to rehabilitation centers, Mr. G usually would resume drinking soon after he was discharged. Three days ago, Mr. G’s wife had told him she “could not take it anymore,” so he got rid of all his alcohol and stopped drinking. Mr. G’s wife felt he was doing fine the first day, but his condition increasingly worsened the second and third days. The triage nurse who attempts to interview Mr. G finds him tremulous, vomiting, and sweating. She notices that he seems preoccupied with pulling at his shirt, appearing to pick at things that are not there.

HISTORY Untreated depression, other comorbidities

Mr. G’s wife says he has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or exhibited suicidal behavior. Mr. G previously received care from a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with major depressive disorder (MDD) and prescribed an antidepressant, though his wife cannot recall which specific medication. She shares it has been “a long time” since Mr. G has taken the antidepressant and the last time he received treatment for his MDD was 5 years ago. Mr. G’s wife says her husband had once abstained from alcohol use for >6 months following one of his stints at a rehabilitation center. She is not able to share many other details about Mr. G’s previous stays at rehabilitation centers, but says he always had “a rough time.”

She says Mr. G had been drinking an average of 10 drinks each night, usually within 4 hours. He has no history of nicotine or illicit substance use and has held a corporate job for the last 18 years. Several years ago, a physician had diagnosed Mr. G with hypertension and high cholesterol, but he did not follow up for treatment. Mr. G’s wife also recalls a physician told her husband he had a fatty liver. His family history includes heart disease and cancer.

The author’s observations

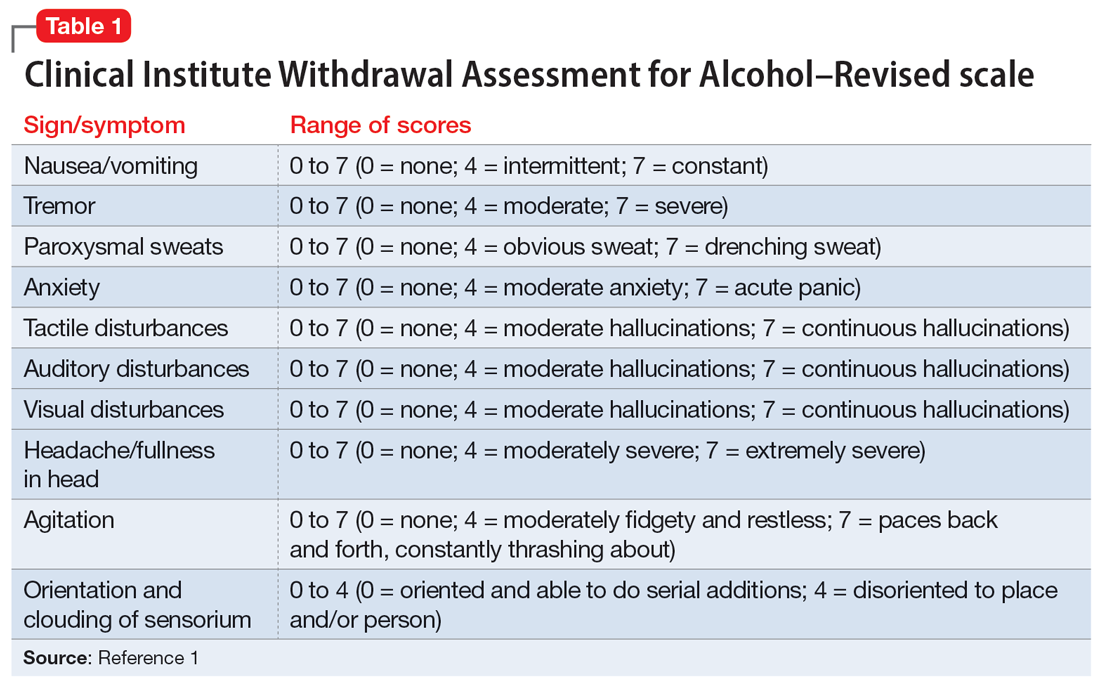

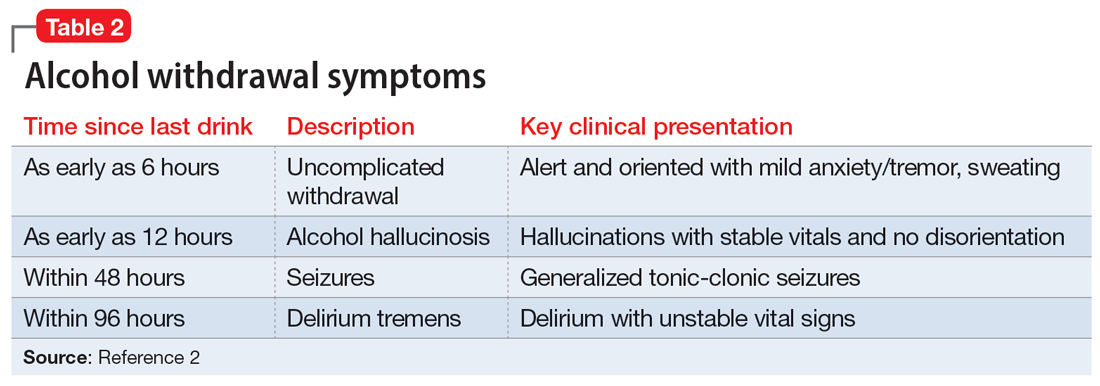

The treatment team observed several elements of alcohol withdrawal and classified Mr. G as a priority patient. If the team had completed the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale (CIWA-Ar) (Table 11), Mr. G would score ≥10. While the protocol for initiating treatment for patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal varies by institution, patients with moderate to severe scores on the CIWA-Ar when experiencing withdrawal typically are managed with pharmacotherapy to address their symptoms.1 Given the timeline of his last drink as reported by his wife, Mr. G is on the brink of experiencing a cascade of symptoms concerning for delirium tremens (DTs).2 Table 22 provides a timeline and symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. To prevent further exacerbation of symptoms, which could lead to DTs, Mr. G’s treatment team will likely initiate a benzodiazepine, using either scheduled or symptom-driven dosing.3

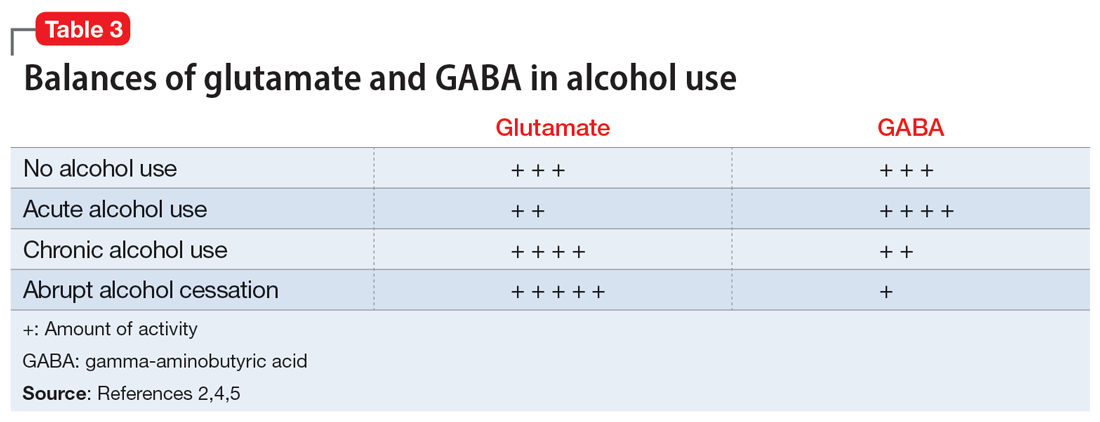

Two neurotransmitters that play a role in DTs are glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory). In a normal state, the competing actions of these neurotransmitters balance each other. Acute alcohol intake causes a shift in the excitatory and inhibitory levels, with more inhibition taking place, thus causing disequilibrium. If chronic alcohol use continues, the amount of GABA inhibition reduction is related to downregulation of receptors.2,4 Excitation increases by way of upregulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.2,4,5 The goal is to achieve equilibrium of the neurotransmitters, even though the balance is different from when alcohol was not present.2,4

If alcohol is suddenly removed following chronic use, there is unchecked glutamate excitation related to a blunted GABA state. This added increase in the excitation of glutamate leads to withdrawal symptoms.2,4 Table 32,4,5 depicts the neurotransmitter equilibrium of GABA and glutamate relative to alcohol use.

EVALUATION Bleeding gums and bruising

The treatment team admits Mr. G to the triage bay and contacts the addiction psychiatrist. The physician orders laboratory tests to assess nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities. Mr. G is also placed on routine assessments with symptom-triggered therapy. An assessment reveals bleeding gums and bruises, which are believed to be a result of thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

Continue to: The author's observations