Mr. S, age 77, is admitted to a long-term care facility due to progressive cognitive impairment and sexually inappropriate behavior. He has a history of sexual assault of medical staff. His medical history includes significant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral disturbances, abnormal sexual behaviors, subclinical hypothyroidism, schizoid personality disorder, Parkinson disease, posttraumatic stress disorder, and hyperammonemia.

Upon admission, Mr. S’s vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (4.54 mIU/L; reference range 0.40 to 4.50 mIU/L). Prior cognitive testing results and updated ammonia levels are unavailable. Mr. S’s current medications include acetaminophen 650 mg every 4 hours as needed for pain, calcium carbonate/vitamin D twice daily for bone health, carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg twice daily for Parkinson disease, melatonin 3 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, quetiapine 25 mg twice daily for psychosis with disturbance of behavior and 12.5 mg every 4 hours as needed for agitation, and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia. Before Mr. S was admitted, previous therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had been tapered and discontinued. Mr. S had also started antipsychotic therapy at another facility due to worsening behaviors.

In patients with dementia, the brain is experiencing neurodegeneration. Progressively, neurons may stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and ultimately face cell death. The specific dementia diagnosis and its clinical features depend on the type of neurons and region of the brain affected.1,2

FTD occurs in response to damage to the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobe correlates to executive functioning, while the temporal lobe plays a role in speech and comprehension. Damage to these areas may result in loss of movement, trouble speaking, difficulty solving complex problems, and problems with social behavior. Specifically, damage to the orbital frontal cortex may cause disinhibition and abnormal behaviors, including emotional lability, vulgarity, and indifference to social nuances.1 Within an FTD diagnosis, there are 3 disorders: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia.1 Specifically, bvFTD can result in abnormal sexual behaviors such as making sexually inappropriate statements, masturbating in public, undressing in public, inappropriately or aggressively touching others, or confusing another individual as an intimate partner. In addition to cognitive impairment, these neurobehavioral symptoms can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life while increasing caregiver burden.2

Occurring at a similar frequency to Alzheimer’s disease in patients age <65, FTD is one of the more common causes of early-onset dementia. The mean age of onset is 58 and onset after age 75 is particularly unusual. Memory may not be affected early in the course of the disease, but social changes are likely. As FTD progresses, symptoms will resemble those of Alzheimer’s disease and patients will require assistance with activities of daily living. In later stages of FTD, patients will exhibit language and behavior symptoms. Due to its unique progression, FTD can be commonly misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses or neurocognitive disorders.1

Approaches to treatment: What to consider

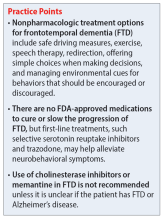

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are appropriate for addressing FTD. Because nonpharmacologic options improve patient safety and overall physical health, they should be used whenever practical. These interventions include safe driving measures, exercise, speech therapy, redirection, offering simple choices when making decisions, and managing environmental cues for behaviors that should be encouraged or discouraged.3

There are no FDA-approved medications to cure or slow the progression of FTD. Therefore, treatment is focused on alleviating neurobehavioral symptoms. The symptoms depend on the type of FTD the patient has; they include cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbances, compulsive behaviors, speech and language problems, and agitation. While many medications have been commonly used for symptomatic relief, evidence for the efficacy of these treatments in FTD is limited.2

Continue to: A review of the literature...