Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative condition diagnosed pathologically by alpha synuclein–containing Lewy bodies and dopaminergic cell loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta of the midbrain. Loss of dopaminergic input to the caudate and putamen disrupts the direct and indirect basal ganglia pathways for motor control and contributes to the motor symptoms of PD.1 According to the Movement Disorder Society criteria, PD is diagnosed clinically by bradykinesia (slowness of movement) plus resting tremor and/or rigidity in the presence of supportive criteria, such as levodopa responsiveness and hyposmia, and in the absence of exclusion criteria and red flags that would suggest atypical parkinsonism or an alternative diagnosis.2

Although the diagnosis and treatment of PD focus heavily on the motor symptoms, nonmotor symptoms can arise decades before the onset of motor symptoms and continue throughout the lifespan. Nonmotor symptoms affect patients from head (ie, cognition and mood) to toe (ie, striatal toe pain) and multiple organ systems in between, including the olfactory, integumentary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and autonomic nervous systems. Thus, it is not surprising that nonmotor symptoms of PD impact health-related quality of life more substantially than motor symptoms.3 A helpful analogy is to consider the motor symptoms of PD as the tip of the iceberg and the nonmotor symptoms as the larger, submerged portions of the iceberg.4

Nonmotor symptoms can negatively impact the treatment of motor symptoms. For example, imagine a patient who is very rigid and dyscoordinated in the arms and legs, which limits their ability to dress and walk. If this patient also suffers from nonmotor symptoms of orthostatic hypotension and psychosis—both of which can be exacerbated by levodopa—dose escalation of levodopa for the rigidity and dyscoordination could be compromised, rendering the patient undertreated and less mobile.

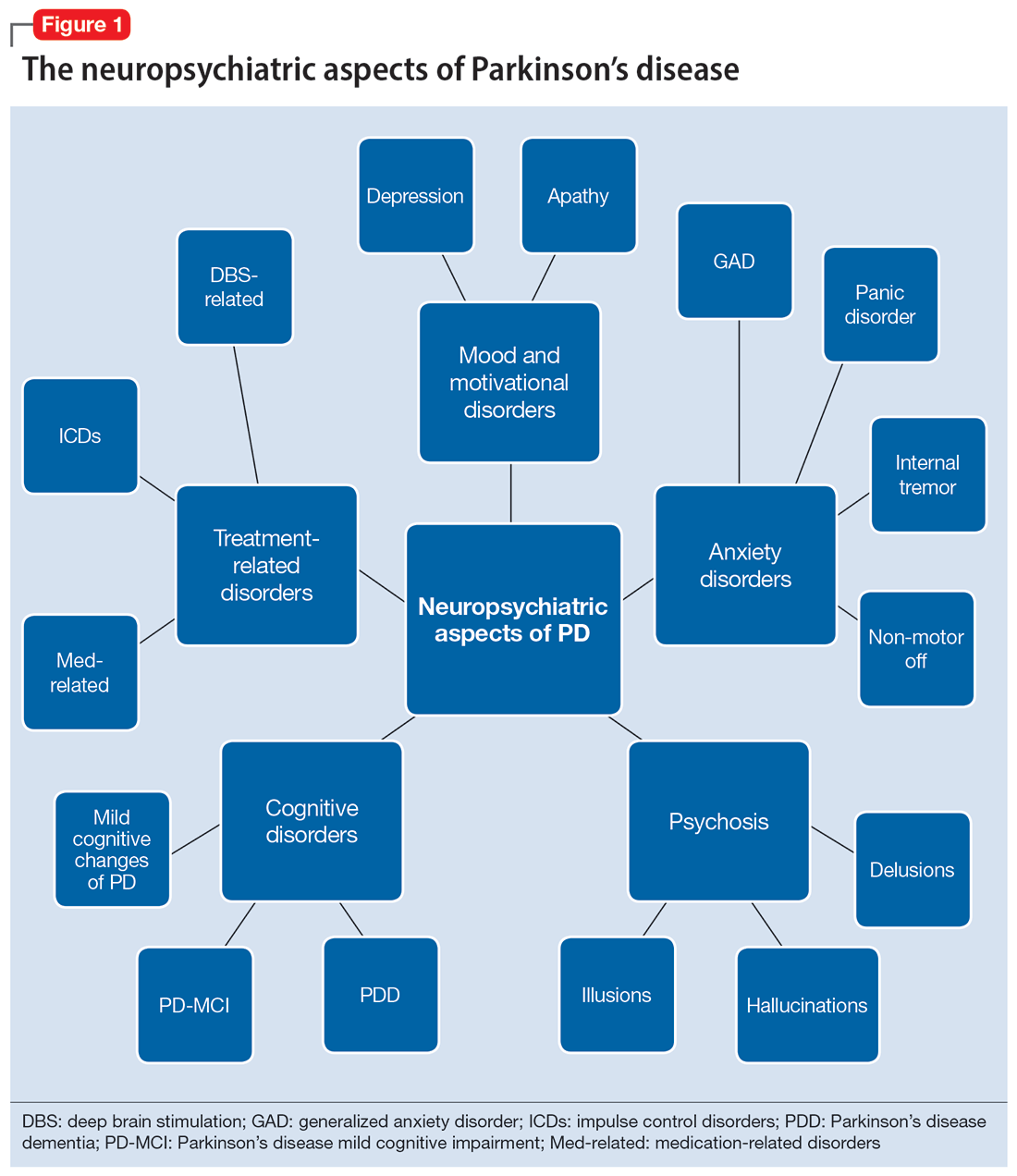

In this review, we focus on identifying and managing nonmotor symptoms of PD that are relevant to psychiatric practice, including mood and motivational disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis, cognitive disorders, and disorders related to the pharmacologic and surgical treatment of PD (Figure 1).

Mood and motivational disorders

Depression

Depression is a common symptom in PD that can occur in the prodromal period years to decades before the onset of motor symptoms, as well as throughout the disease course.5 The prevalence of depression in PD varies from 3% to 90%, depending on the methods of assessment, clinical setting of assessment, motor symptom severity, and other factors; clinically significant depression likely affects approximately 35% to 38% of patients.5,6 How depression in patients with PD differs from depression in the general population is not entirely understood, but there does seem to be less guilt and suicidal ideation and a substantial component of negative affect, including dysphoria and anxiety.7 Practically speaking, depression is treated similarly in PD and general populations, with a few considerations.

Despite limited randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for efficacy specifically in patients with PD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are generally considered first-line treatments. There is also evidence for tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but due to potential worsening of orthostatic hypotension and cognition, TCAs may not be a favorable option for certain patients with PD.8,9 All antidepressants have the potential to worsen tremor. Theoretically, SNRIs, with noradrenergic activity, may be less tolerable than SSRIs in patients with PD. However, worsening tremor generally has not been a clinically significant adverse event reported in PD depression clinical trials, although it was seen in 17% of patients receiving paroxetine and 21% of patients receiving venlafaxine compared to 7% of patients receiving placebo.9-11 If tremor worsens, mirtazapine could be considered because it has been reported to cause less tremor than SSRIs or TCAs.12

Among medications for PD, pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, may have a beneficial effect on depression.13 Additionally, some evidence supports rasagiline, a monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor, as an adjunctive medication for depression in PD.14 Nevertheless, antidepressant medications remain the standard pharmacologic treatment for PD depression.

Continue to: In terms of nonpharmacologic options...