Delirious mania is a syndrome characterized by the acute onset of severe hyperactivity, psychosis, catatonia, and intermittent confusion. While there have been growing reports of this phenomenon over the last 2 decades, it remains poorly recognized and understood.1,2 There is no widely accepted nosology for delirious mania and the condition is absent from DSM-5, which magnifies the difficulties in making a timely diagnosis and initiating appropriate treatment. Delayed diagnosis and treatment may result in a detrimental outcome.2,3 Delirious mania has also been labeled as lethal catatonia, specific febrile delirium, hyperactive or exhaustive mania, and Bell’s mania.2,4,5 The characterization and diagnosis of this condition have a long and inconsistent history (Box1,6-11).

Box

Delirious mania was originally recognized in 1849 by Luther Bell in McLean Hospital after he observed 40 cases that were uniquely distinct from 1,700 other cases from 1836 to 1849.6 He described these patients as being suddenly confused, demonstrating unprovoked combativeness, remarkable decreased need for sleep, excessive motor restlessness, extreme fearfulness, and certain physiological signs, including rapid pulse and sweating. Bell was limited to the psychiatric treatment of his time, which largely was confined to physical restraints. Approximately three-fourths of these patients died.6

Following Bell’s report, this syndrome remained unexplored and rarely described. Some researchers postulated that the development of confusion was a natural progression of late-phase mania in close to 20% of patients.7 However, this did not account for the rapid onset of symptoms as well as certain unexplained movement abnormalities. In 1980, Bond8 presented 3 cases that were similar in nature to Bell’s depiction: acute onset with extraordinary irritability, withdrawal, delirium, and mania.

For the next 2 decades, delirious mania was seldom reported in the literature. The term was often reserved to illustrate when a patient had nothing more than mania with features of delirium.9

By 1996, catatonia became better recognized in its wide array of symptomology and diagnostic scales.10,11 In 1999, in addition to the sudden onset of excitement, paranoia, grandiosity, and disorientation, Fink1 reported catatonic signs including negativism, stereotypy, posturing, grimacing, and echo phenomena in patients with delirious mania. He identified its sensitive response to electroconvulsive therapy.

Delirious mania continues to be met with incertitude in clinical practice, and numerous inconsistencies have been reported in the literature. For example, some cases that have been reported as delirious mania had more evidence of primary delirium due to another medical condition or primary mania.12,13 Other cases have demonstrated swift improvement of symptoms after monotherapy with antipsychotics without a trial of benzodiazepines or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); the exclusion of a sudden onset questions the validity of the diagnosis and promotes the use of less efficacious treatments.14,15 Other reports have confirmed that the diagnosis is missed when certain symptoms are more predominant, such as a thought disorder (acute schizophrenia), grandiosity and delusional ideation (bipolar disorder [BD]), and less commonly assessed catatonic signs (ambitendency, automatic obedience). These symptoms are mistakenly attributed to the respective disease.1,16 This especially holds true when delirious mania is initially diagnosed as a primary psychosis, which leads to the administration of antipsychotics.17 Other cases have reported that delirious mania was resistant to treatment, but ECT was never pursued.18

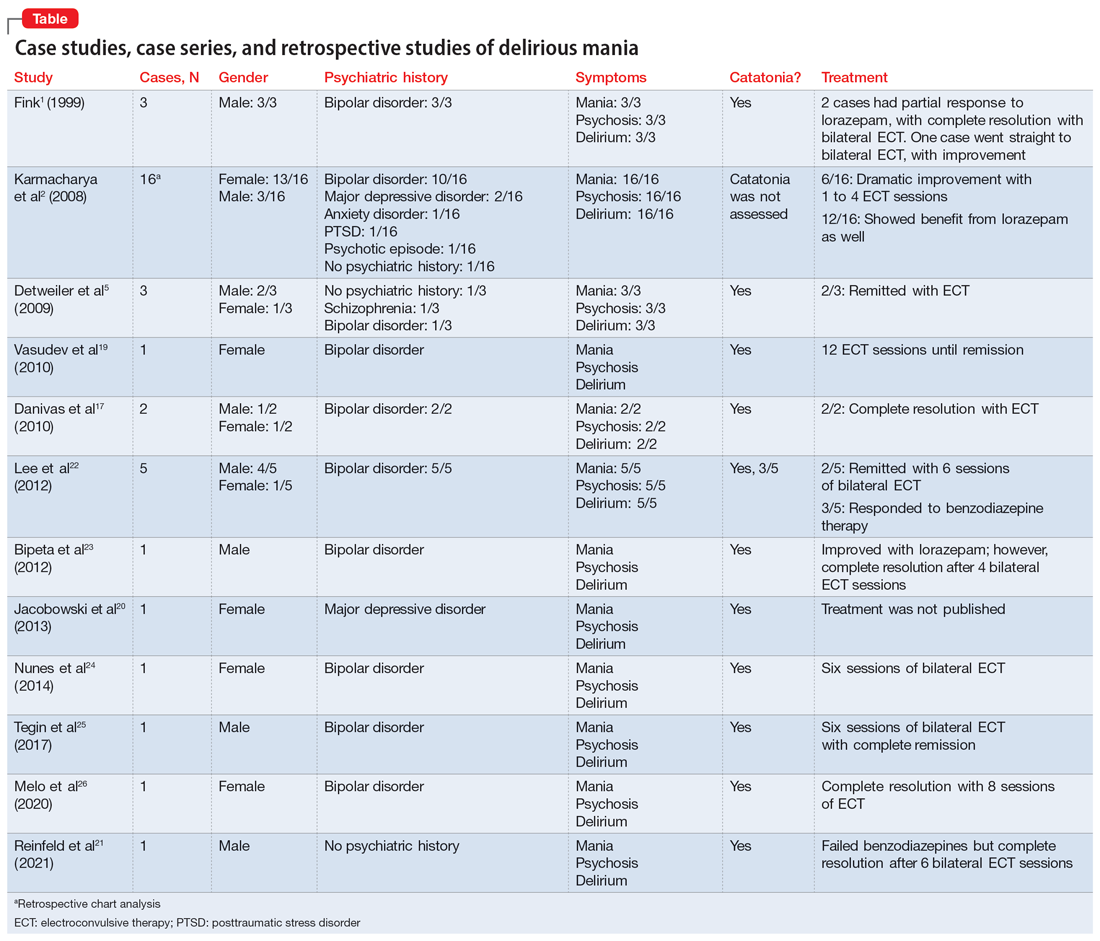

In this review, we provide a more comprehensive perspective of the clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management of delirious mania. We searched PubMed and Google Scholar using the keywords “delirious mania,” “delirious mania AND catatonia,” or “manic delirium.” Most articles we found were case reports, case series, or retrospective chart reviews. There were no systematic reviews, meta analyses, or randomized control trials (RCTs). The 12 articles included in this review consist of 7 individual case reports, 4 case series, and 1 retrospective chart review that describe a total of 36 cases (Table1,2,5,17,19-26).

Clinical presentation: What to look for

Patients with delirious mania typically develop symptoms extremely rapidly. In virtually all published literature, symptoms were reported to emerge within hours to days and consisted of severe forms of mania, psychosis, and delirium; 100% of the cases in our review had these symptoms. Commonly reported symptoms were:

- intense excitement

- emotional lability

- grandiose delusions

- profound insomnia

- pressured and rapid speech

- auditory and visual hallucinations

- hypersexuality

- thought disorganization.

Exquisite paranoia can also result in violent aggression (and may require the use of physical restraints). Patients may confine themselves to very small spaces (such as a closet) in response to the intense paranoia. Impairments in various neurocognitive domains—including inability to focus; disorientation; language and visuospatial disturbances; difficulty with shifting and sustaining attention; and short-term memory impairments—have been reported. Patients often cannot recall the events during the episode.1,2,5,27,28

Catatonia has been closely associated with delirious mania.29 Features of excited catatonia—such as excessive motor activity, negativism, grimacing, posturing, echolalia, echopraxia, stereotypy, automatic obedience, verbigeration, combativeness, impulsivity, and rigidity—typically accompany delirious mania.1,5,10,19,27

In addition to these symptoms, patients may engage in specific behaviors. They may exhibit inappropriate toileting such as smearing feces on walls or in bags, fecal or urinary incontinence, disrobing or running naked in public places, or pouring liquid on the floor or on one’s head.1,2

Continue to: Of the 36 cases...