After several months of difficulty living in her current apartment complex, Ms. M asks you as her psychiatrist to write a letter to the management company requesting she be moved to an apartment on the opposite side of the maintenance closet because the noise aggravates her posttraumatic stress disorder. What should you consider when asked to write such a letter?

Psychiatric practice often extends beyond the treatment of mental illness to include addressing patients’ social well-being. Psychiatrists commonly inquire about a patient’s social situation to understand the impact of these environmental factors. Similarly, psychiatric illness may affect a patient’s ability to work or fulfill responsibilities. As a result, patients may ask their psychiatrists for assistance by requesting letters that address various aspects of their social well-being.1 These communications may address an array of topics, from a patient’s readiness to return to work to their ability to pay child support. This article focuses on the role psychiatrists have in writing patient-requested letters across a variety of topics, including the consideration of potential legal liability and ethical implications.

Types of letters

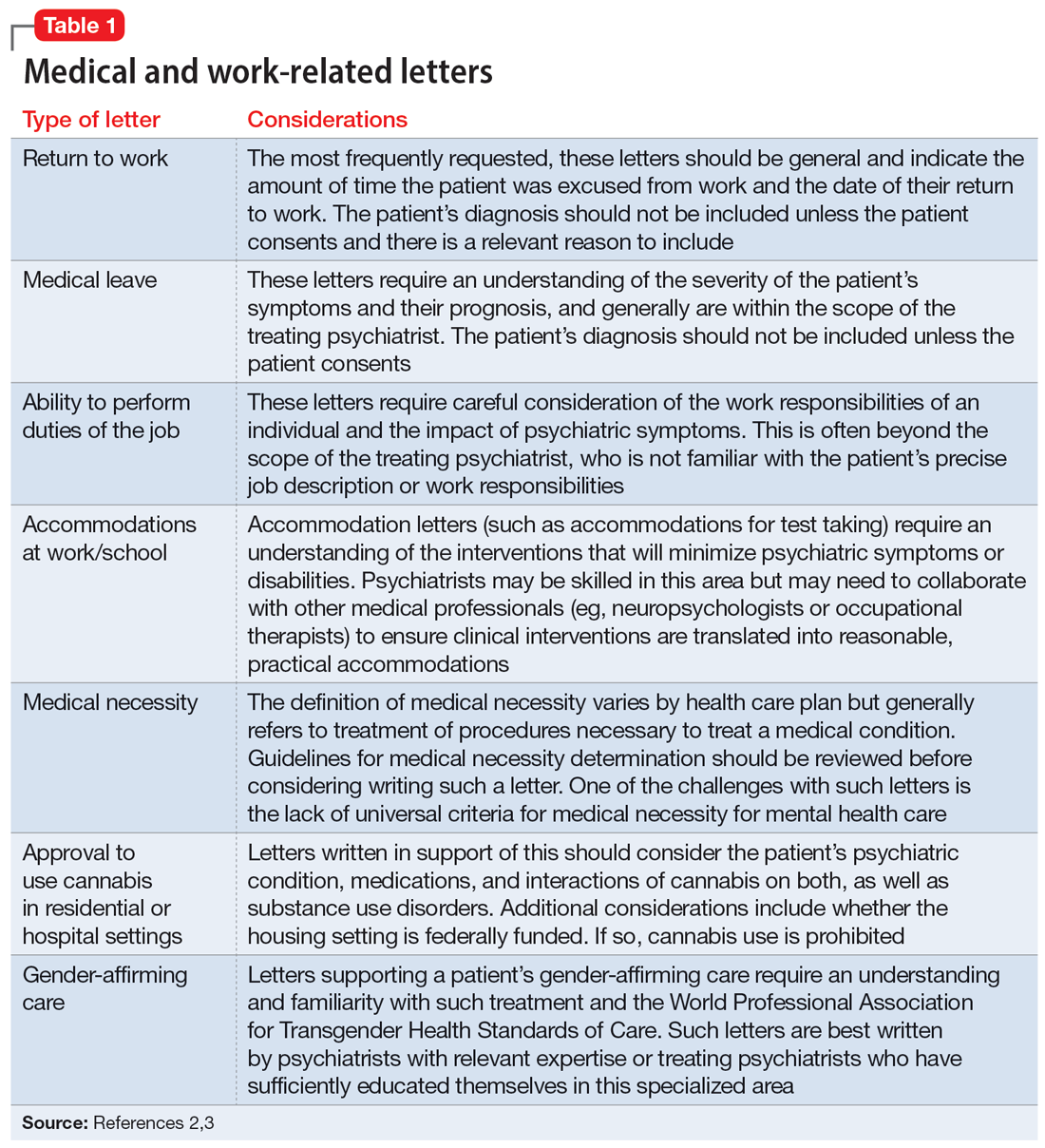

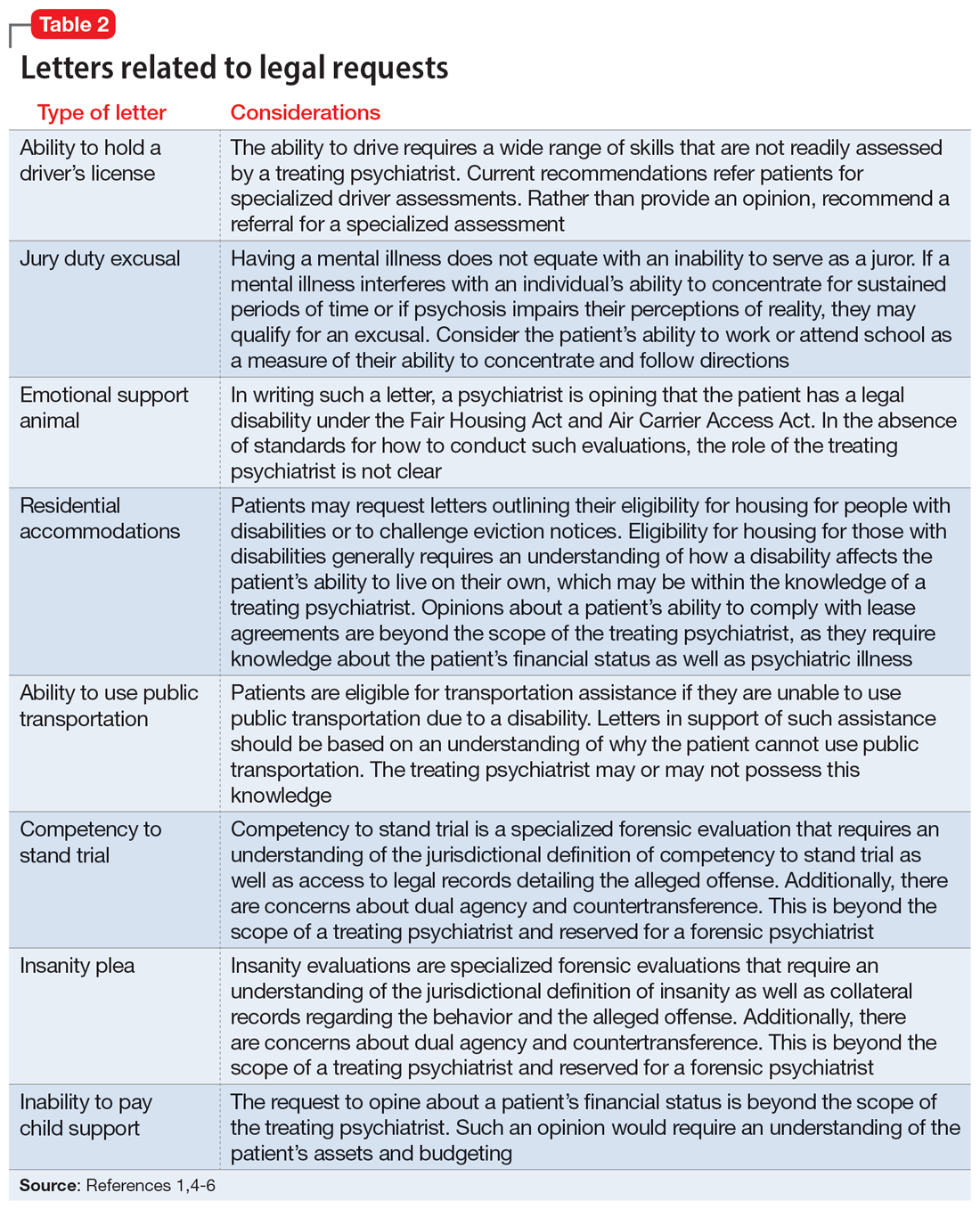

The categories of letters patients request can be divided into 2 groups. The first is comprised of letters relating to the patient’s medical needs (Table 12,3). These address the patient’s ability to work (eg, medical leave, return to work, or accommodations) or travel (eg, ability to drive or use public transportation), or need for specific medical treatment (ie, gender-affirming care or cannabis use in specific settings). The second group relates to legal requests such as excusal from jury duty, emotional support animals, or any other letter used specifically for legal purposes (in civil or criminal cases) (Table 21,4-6).

The decision to write a letter on behalf of a patient should be based on whether you have sufficient knowledge to answer the referral question, and whether the requested evaluation fits within your role as the treating psychiatrist. Many requests fall short of the first condition. For example, a request to opine about an individual’s ability to perform their job duties requires specific knowledge and careful consideration of the patient’s work responsibilities, knowledge of the impact of their psychiatric symptoms, and specialized knowledge about interventions that would ameliorate symptoms in the specialized work setting. Most psychiatrists are not sufficiently familiar with a specific workplace to provide opinions regarding reasonable accommodations.

The second condition refers to the role and responsibilities of the psychiatrist. Many letter requests are clearly within the scope of the clinical psychiatrist, such as a medical leave note due to a psychiatric decompensation or a jury duty excusal due to an unstable mental state. Other letters reach beyond the role of the general or treating psychiatrist, such as opinions about suitable housing or a patient’s competency to stand trial.

Components of letters

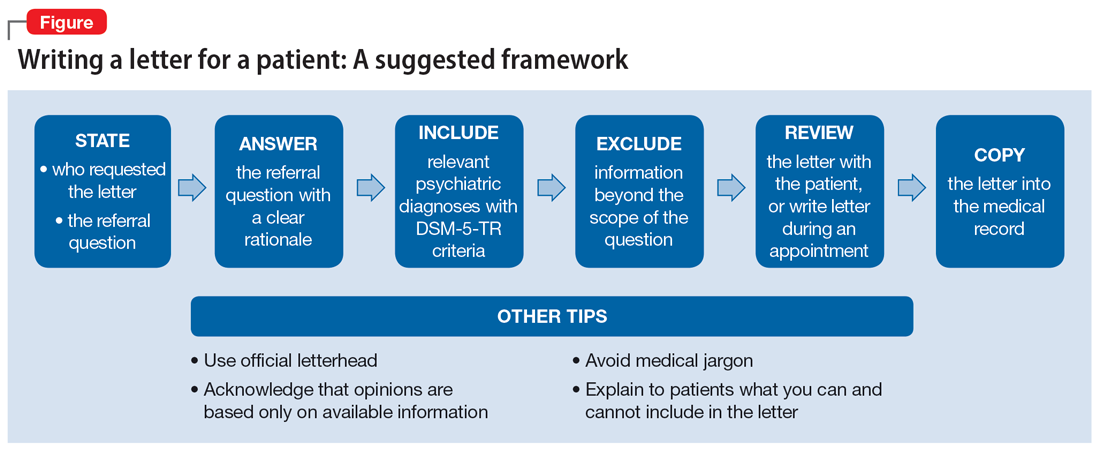

The decision to write or not to write a letter should be discussed with the patient. Identify the reasons for and against letter writing. If you decide to write a letter, the letter should have the following basic framework (Figure): the identity of the person who requested the letter, the referral question, and an answer to the referral question with a clear rationale. Describe the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis using DSM criteria. Any limitations to the answer should be identified. The letter should not go beyond the referral question and should not include information that was not requested. It also should be preserved in the medical record.

It is recommended to write or review the letter in the presence of the patient to discuss the contents of the letter and what the psychiatrist can or cannot write. As in forensic reports, conclusory statements are not helpful. Provide descriptive information instead of relying on psychiatric jargon, and a rationale for the opinion as opposed to stating an opinion as fact. In the letter, you must acknowledge that your opinion is based upon information provided by the patient (and the patient’s family, when accurate) and as a result, is not fully objective.

Continue to: Liability and dual agency