Evidence that atypical antipsychotics can increase risk of diabetes and heart disease is changing psychiatry’s approach to laboratory testing. The need for careful psychotropic prescribing—with intelligent use of diagnostic testing—has been emphasized by:

- four medical associations recommending that physicians screen and monitor patients taking atypical antipsychotics.

- FDA requiring antipsychotic labeling to describe increased risk of hyperglycemia and diabetes

- medical malpractice lawyers using television and Internet ads to seek clients who might have developed diabetes while taking antipsychotics.

This article offers information you need to detect emerging metabolic problems in patients taking atypical antipsychotics. We also discuss five other clinical situations where laboratory testing can help you:

- rule out organic illness

- perform therapeutic drug monitoring

- protect the heart when prescribing

- watch for clozapine’s side effects

- monitor for substance abuse.

Table 1

Lab testing with atypical antipsychotics*

Obtain baseline values before or as soon as possible after starting the antipsychotic:

Also note patient/family histories of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart disease† |

Repeat diabetes monitoring with fasting blood glucose and/or Hb A1c after 3 months of treatment, then at least annually. More-frequent monitoring (quarterly or monthly) may be indicated for patients with:

|

Consider switching to a medication with less weight-gain liability‡ for patients:

|

| Identify patients with metabolic syndrome,§ and ensure that they are carefully monitored by a primary care clinician. Check weight (with BMI) monthly for all patients for the first 6 months, then every 3 months thereafter |

| Repeat fasting lipid profile after 3 months, then every 2 years if serum lipids are normal or every 6 months in consultation with primary care clinician if LDL >130 mg/dL |

| * Individualize to particular patients’ needs. |

| † Patients with schizophrenia are at increased risk of coronary heart disease. |

| ‡ Weight gain liability = clozapine, olanzapine > risperidone, quetiapine > aripiprazole, ziprasidone |

| § Metabolic syndrome: A proinflammatory, prothrombotic state described by a cluster of abnormalities including abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, hypertension, and low HDL cholesterol. Can be exacerbated by atypical antipsychotics. |

| Source: Adapted from reference 3. |

DIABETES RISK

New monitoring standards. The American Psychiatric Association set a new standard of care by collaborating with the American Diabetes Association and others in recommending how to manage the potential for increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and lipid disorders when using atypical antipsychotics.2 The February 2004 APA/ADA report cites olanzapine and clozapine as the atypicals most likely to cause metabolic changes that increase heart disease risk. It also notes, however, that atypicals’ potential benefits to certain patients outweigh the risks.

Because of this report, psychiatrists who prescribe atypicals are now obligated to document baseline lab values and monitor patients for potential side effects (Table 1).1 We recommend that you also note patient race, as certain ethnic populations (such as African-American, Hispanic, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander) are at elevated risk for diabetes.

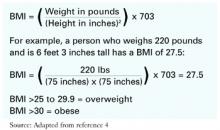

Determining BMI. When starting patients on atypical antipsychotics, calculate baseline body mass index (BMI) with the simple formula in Table 2 or by using BMI tables (see Related resources).4 Determine BMI before starting a new atypical antipsychotic, at every visit for the first 6 months, and then quarterly when the dosage is stable.

A BMI increase of 1 unit warrants medical intervention, including increased weight monitoring and placing the patient in a weight-management program and switching to another antipsychotic.3

Table 2 An easy formula to calculate body mass index (BMI)

The increasing incidence of diabetes in the U.S. population makes it difficult to assess the relationship between atypical antipsychotic use and blood glucose abnormalities. Moreover, the risk of diabetes may be elevated in patients with schizophrenia, whether or not they are receiving medications. Diabetes and disturbed carbohydrate metabolism may be an integral component of schizophrenia itself.1

RULING OUT ORGANIC ILLNESS

A classic role of laboratory and diagnostic testing in psychiatry is to exclude organic illness that may be causing or exacerbating psychiatric symptoms. For a patient presenting with serious psychiatric symptoms, most sources recommend a standard battery of screening tests (Table 3).

Of course, the DSM-IV-TR “mental disorder due to a general medical condition” should be included in the differential diagnosis of any psychiatric presentation. DSM-IV-TR also calls for disease-specific tests, such as polysomnography in certain sleep disorders, CT for enlarged ventricles in schizophrenia, and electrolyte analysis in patients with anorexia nervosa.5 Order other tests as indicated, depending on patients’ medical conditions.