Benzodiazepine-induced delirium. A recent meta-analysis suggested that benzodiazepines may be associated with an increased risk of delirium.16 Longer-acting benzodiazepines may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with short-acting agents, and higher doses during a 24-hour period may be associated with increased risk of delirium compared with lower doses. However, wide confidence intervals imply significant uncertainty with these results, and not all patients in the studies reviewed were undergoing alcohol detoxification.16 Benzodiazepines have been reported to accentuate delirium when used to treat DTs.17

We postulate that although Mr. J received lorazepam—a short- to moderate-acting benzodiazepine with a half-life of 12 to 16 hours18—the cumulative dose was high enough to have accentuated—rather than attenuated—delirium.16

Personality disorders. Comorbid alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and personality disorders are well documented. One study found the prevalence of personality disorders in AUDs ranged from 22% to 78%.19 Psychologically, drinking to cope with negative subjective states and emotions (coping motives) and drinking to enhance positive emotions (enhancement motives) may explain the relation between Cluster B personality disorders and AUDs.20

Research on prefrontal functioning in alcoholics and individuals with antisocial personality disorder symptoms has suggested that both groups may be impaired on tasks sensitive to compromised orbitofrontal functioning.21 The orbitofrontal system is essential for maintaining normal inhibitory influences on behavior.22 Benzodiazepines can increase the likelihood of developing disinhibition or impulsivity, which are symptoms of antisocial personality disorder. Because Mr. J had antisocial personality disorder, treating his alcohol withdrawal with a benzodiazepine could have accentuated these symptoms, which were subsequently “treated” with additional lorazepam, therefore worsening the cycle.

Medical comorbidities. The CIWA-Ar relies on autonomic signs and subjective symptoms and was not designed for use in nonverbal patients in the ICU. It is possible that the presence of other acute illnesses may contribute to increased CIWA-Ar scores, but we are unaware of any studies that have evaluated such factors.23

However, tremor, which is scored on the CIWA-Ar, can falsely elevate scores if it is caused by something other than acute alcohol withdrawal. Although essential tremors attenuate with acute alcohol use, chronic alcohol use can result in parkinsonism with a resting tremor, and cerebellar degeneration, which can include an action tremor and cerebellar 3-Hz leg tremor.24 Finally, hepatic encephalopathy—a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by disturbances in consciousness, mood, behavior, and cognition—can occur in patients with advanced liver disease, which may be precipitated by alcohol use. The clinical presentation and symptom severity of hepatic encephalopathy varies from minor cognitive impairment to gross disorientation, confusion, and agitation,25 all of which can elevate CIWA-Ar scores.

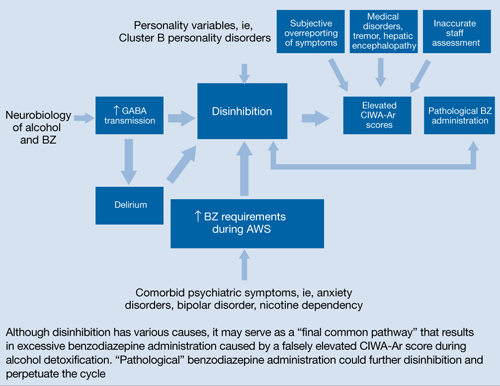

The role of disinhibition

Disinhibition could serve as the “final common pathway” through which CIWA-Ar scores can be falsely elevated.11 For a Figure that illustrates this, see below. Mr. J presented with several variables that could have elevated his CIWA-Ar score; additional potential factors include other psychiatric diagnoses such as bipolar disorder, opiate withdrawal, dementia, drug-seeking behavior, or malingering.26,27

Treating disinhibition in patients with alcohol withdrawal. Continuing to administer escalating doses of benzodiazepines is counterintuitive for benzodiazepine-induced disinhibition. In a study of alcohol withdrawal in rats, antipsychotics evaluated had some beneficial effects on alcohol withdrawal signs.28 In this study, the comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics was as follows: risperidone = quetiapine > ziprasidone > clozapine > olanzapine.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine’s practice guideline advises against using antipsychotics as the sole agent for DTs because these agents are associated with a longer duration of delirium, higher complication rates, and higher mortality.28 However, antipsychotics have a role as an adjunct to benzodiazepines when benzodiazepines don’t sufficiently control agitation, thought disorder, or perceptual disturbances. Although haloperidol use is well established in this scenario, chlorpromazine is contraindicated because it is epileptogenic, and little information is available on atypical antipsychotics.29 If Mr. J had not responded to tapering lorazepam, evidence would support using haloperidol.

Figure: Unifying concept for pathological BZ administration during alcohol withdrawal syndrome: Disinhibition

AWS: alcohol withdrawal syndrome; BZ: benzodiazepine; CIWA-Ar: Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid

Source: Reference 11Related Resources

- Myrick H, Anton RF. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1998;22(1):38-43. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh22-1/38-43.pdf.

- Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD008537.

Drug Brand Names