Figure 1

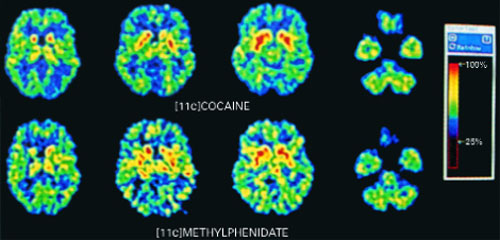

PET scans of the brain using carbon 11 (11C)-labeled cocaine and methylphenidate HCl show similar distributions in the striatium when the drugs are administered intravenously.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Volkow ND, Ding YS, Fowler JS, et al. Is methylphenidate like cocaine? Studies on their pharmacokinetics and distribution in the human brain. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995;52:456-63.

Stimulants are classified as schedule-II drugs because they produce powerful reinforcing effects by increasing synaptic dopamine.7 Positron-emission tomography (PET) scans using carbon labeling have shown similar distributions of methylphenidate and cocaine in the brain (Figure 1).8 When administered intravenously, both drugs occupy the same receptors in the striatum and produce a “high” that parallels rapid neuronal uptake. Methylphenidate and cocaine similarly increase stimulation of the postsynaptic neuron by blocking the dopamine reuptake pump (dopamine transporter).

How a substance gets to the brain’s euphoric receptors greatly affects its addictive properties. Delivery systems with rapid onset—smoking, “snorting,” or IV injection—have much greater ability to produce a “high” than do oral or transdermal routes. The greater the “high,” the greater the potential for abuse.

Because methylphenidate is prescribed for oral use, the potential for abuse is minimal. However, we need to be extremely cautious when giving methylphenidate or similar stimulant medications to patients who have shown they are unable to control their abuse of other substances.

Stimulants can also re-ignite a dormant substance abuse problem. Though little has been written about this in the medical literature, Elizabeth Wurtzel, author of the controversial Prozac Nation, chronicles the resumption of her cocaine abuse in More, Now, Again: A Memoir of Addiction. She contends that after her doctor added methylphenidate to augment treatment of partially remitting depression, she began abusing it and eventually was using 40 tablets per day before slipping back into cocaine dependence.

- Patients with prefrontal cortex deficits can have problems with inattention and poor impulse control.

- Patients with ADHD have frontal lobe impairments, as neuropsychological testing and imaging studies have shown.

- Norepinephrine neurons, with cell bodies in the locus coeruleus, have projections that terminate in the prefrontal cortex.

- Agents with norepinephrine activity, but without mood-altering properties (e.g., clonidine), have been shown to improve ADHD symptoms.

Table 1

ADHD IN ADULTS: ANTIDEPRESSANT DOSAGES AND SIDE EFFECTS

| Medication | Class | Effective dosage | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desipramine | Tricyclic | 100 to 200 mg/d | Sedation, weight gain, dry mouth, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, prolonged cardiac conduction time; may be lethal in overdose |

| Bupropion SR | Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor | 150 mg bid to 200 mg bid | Headaches, insomnia, agitation, increased risk of seizures |

| Venlafaxine XR | Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 75 to 225 mg/d | Nausea, sexual side effects, agitation, increased blood pressure at higher dosages |

| Atomoxetine* | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | To be determined | To be determined |

| * Investigational agent; not FDA-approved | |||

Additional evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex has projections back to the locus coeruleus, which may explain the relationship between the two areas. It may be that the brain’s higher-functioning areas, such as the prefrontal cortex, provide intelligent screening of impulses from the brain’s older areas, such as the locus coeruleus. Therefore, increased prefrontal cortex activity may modulate some impulses that ADHD patients cannot control otherwise.

No ‘high’ with antidepressants. Patients with ADHD who have experienced the powerful effects of street drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, or even alcohol may report that antidepressants do not provide the effect they desire. It is difficult to know if these patients are reporting a lack of benefit or simply the absence of a euphoric “high” they are used to experiencing with substances of abuse. The newer antidepressants do not activate the brain’s euphoric receptors to an appreciable degree.

Patients who take stimulants as prescribed also do not report a “high” but can detect the medication’s presence and absence. Most do not crave this feeling, but substance abusers tend to like it. A patient recently told me he didn’t think stimulants improved his ADHD, but said, “I just liked the way they made me feel.”

Desipramine

The tricyclic antidepressant desipramine is a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that is effective in treating ADHD in children and adults. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adults with ADHD, subjects receiving desipramine showed robust improvement in symptom scores on the ADHD Rating Scale,16 compared with those receiving the placebo (Figure 2).17

During the 6-week trial, 41 adults with ADHD received desipramine, 200 mg/d, or a placebo. Those receiving desipramine showed significant improvement in 12 of 14 ADHD symptoms and less hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattentiveness, whereas those receiving the placebo showed no improvement. According to the study criteria, 68% of those who received desipramine and none who received the placebo were considered positive responders.