“Will this patient turn violent?” Psychiatrists face this tough question every day. Although predicting a complex behavior such as violence is nearly impossible, we can prepare for dangerous behavior and improve our safety by:

- knowing the risk factors for patient violence

- assessing individuals for violence potential before clinical encounters

- controlling situations to reduce injury risk.

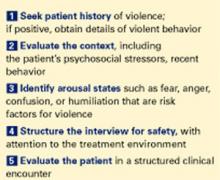

In one study, more than 50% of psychiatrists and 75% of mental health nurses reported an act or threat of violence from patients within the past year.1 To help you avoid becoming a statistic, this article provides a 5-step procedure (Figure 1). to quickly assess and respond to risk of violence in a psychiatric patient.

Step 1: Seek patient history

A careful review of past events and those immediately preceding the clinical encounter is the best tool for assessing potential for violence. The more you can learn from the patient chart and other sources before you see the patient, the better (Table 1). Valuable clues can be obtained from interviews with family members, outpatient providers, police officers, and others who have had pertinent social contact with the patient.

Figure 5 steps to assess and reduce the risk of patient violence

Past violence is the most powerful predictor of future violence, according to published studies. Higher frequency of aggressive episodes, greater degree of aggressive injury, and lack of apparent provocation in past episodes all increase the violence risk.3

A minority of patients account for most aggressive acts in clinical encounters. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent behaviors in a health care setting.4 A patient’s history of violence should be flagged in the chart and verbally passed on to staff to alert providers of increased risk.

However, not having a violent history does not guarantee that a patient will not become dangerous during a clinical encounter. All patients with a violent past had an initial violent episode, and that first time can occur in a practice setting.

Psychotic states by themselves appear to increase the risk of violence, although the literature is mixed.5,6 Clearly, however, psychotic states associated with arousal or agitation do predispose patients to violence, especially if the psychosis involves active paranoid delusions or hallucinations associated with negative affect (anger, sadness, anxiety).7

Increased rates of violence have also been reported in psychiatric patients with:

- acute manic states associated with arousal or agitation8

- nonspecific neurologic abnormalities such as abnormal EEGs, localizing neurologic signs, or “soft signs” (impaired face-hand test, graphesthesia, stereognosis).9

Demographic variables associated with higher violence rates include ages 15 to 24, nonwhite race, male gender, poverty, and low educational level. Other variables include history of abuse, victimization, family violence, limited employment skills, and “rootlessness,” such as poor family network and frequent moves or job changes.10

Psychiatric diagnoses associated with increased risk of violence include schizophrenia, bipolar mania, alcohol and other substance abuse, and personality disorders.11-13 In clinical practice, however, I find psychiatric diagnoses less useful in predicting violence than the patient’s arousal state and the other risk factors discussed above.

Step 2: Evaluate the context

In addition to evidence-supported risk factors (Table 2), context—or the broader situation in which a patient is embedded at the time of psychiatric evaluation—plays a prominent role in potentially violent situations. For example, if “divorce” is listed as a presenting factor:

- Is the patient recently divorced, or did it occur years ago?

- Does he hate all women or just his ex-wife?

- Was she having an affair, and did he just learn about this?

In other words, environmental stresses can be acute and destabilizing or part of the patient’s chronic life picture and serve in homeostatic functioning.

Step 3: Identify arousal states

Patients rarely commit violent acts when their anxiety and moods are well controlled. They are more likely to become aggressive in high arousal states.

Fear is probably an element of most situations where patients act out violently. Because the fearful patient may not exhibit easily interpreted danger signals, however, you may unwittingly provoke an assault by violating his or her personal space. A fearful, paranoid patient requires a greater-than-usual “intimate zone,” although this need for increased space may not be obvious.

Minimize provocation by explaining your actions and behaviors in advance (such as, “I would like to enter the room, sit down, and talk with you for about 20 minutes”). Be business-like with paranoid patients. Avoid exuding warmth, as they may view attempts at warmth as having sinister intent.

Clinicians are sometimes injured when trying to prevent a fearful, paranoid patient from fleeing. To avoid injury, don’t stand between the patient and the door. Let the patient escape from the immediate situation, and enlist security or police in further intervention attempts.