Just three words—“My tummy hurts”—can mobilize a child’s parents into a high state of worry, especially on school days. They wonder: Is our child sick? Should he or she stay home? Why is this happening so often?

Although recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) is real, it usually is not caused by tissue damage or serious physical disease. When children with RAP are referred for psychiatric evaluation—often after extensive medical workups—we can help them and their parents manage the problem and function more normally. This article:

- describes physiologic mechanisms that may underlie recurrent GI distress

- discusses the high correlation of psychiatric comorbidities with RAP

- recommends judicious laboratory testing

- reviews evidence on medications and psychotherapies to improve RAP symptoms

- offers advice on building a therapeutic alliance with the patient and family.

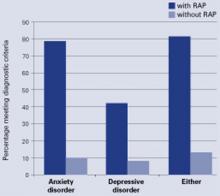

Figure Comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders in children with RAP

Children with functional RAP are much more likely to be anxious or depressed than similar pain-free children. A recent blinded study followed 80 children ages 8 to 15 (42 with RAP and 38 controls) identified through screening at primary care pediatric offices. Each was assessed using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children, Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL). Percentage meeting diagnostic criteria

Source: Reference 5.

RAP: A ‘Functional’ disorder

RAP is a somatoform (or “functional”) disorder, defined as physical symptoms not fully explained by a medical condition, effects of a substance, or another mental disorder. Symptoms cause distress and/or functional impairment and are not intentionally produced.1

A patient with RAP experiences at least three episodes of abdominal pain over 3 months that interfere with daily activities.2 RAP affects 7% to 25% of school-aged children and adolescents,3 most of whom have a functional disorder.4

RAP is equally common among prepubertal boys and girls but more common among girls during adolescence.3 RAP can impair school attendance and performance and stigmatize a child as “sickly.”

Common comorbid symptoms

Physical. Besides stomach pain, children with RAP often experience headaches (including migraines), other GI symptoms, general aches and pains, dizziness, and fatigue.

Patients with RAP who do not experience GI bleeding, anemia, fever, weight loss, growth failure, or persistent vomiting most likely do not have a serious underlying disease.

Psychiatric. Children with RAP have much higher rates of anxiety (80%) and depressive (40%) disorders than do their unaffected peers (Figure).5 We have also seen higher levels of suicidal thinking in children with RAP in primary care settings compared with pain-free controls (14% vs. 4%, P = 0.04; unpublished data).

In most cases, psychiatric comorbidities appear to precede or coincide with RAP onset. Separation fears, generalized anxiety, and social anxiety in particular are common in patients with RAP yet are seldom recognized in medical settings.

Having childhood RAP increases the risk of anxiety, depression, and hypochondriacal fears in adulthood.6 We do not know whether early intervention prevents later disability.

Use of medical services. Abdominal pain accounts for 2% to 4% of all pediatric office visits.7 In one study, 8% of middle school and high school students said they had visited a physician for evaluation of stomach pain during the previous year.8 Children with RAP make more ambulatory health and mental health visits than peers9 and are at risk for unnecessary and potentially dangerous medical tests, procedures, and treatments, including abdominal surgery.10

Four functional GI disorders

To better characterize youths with functional RAP, symptom-based criteria have been developed and applied for functional GI disorders, defined as chronic or recurrent GI symptoms without explanatory structural or biochemical abnormalities.11 Four such disorders are relevant in children with RAP.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): RAP with at least two of the following symptoms: relief with defecation, change in stool frequency, and change in stool form or appearance (occurs in approximately 50% of RAP cases).

Functional dyspepsia: RAP centered in the upper abdomen that is not associated with changes in bowel habits.

Abdominal migraine: Paroxysmal midline abdominal pain lasting 2 hours to several days with symptom-free intervals of weeks to months and at least two of the following: headache during episodes, photophobia during episodes, unilateral headache, aura, and a family history of migraine.

Functional abdominal pain: Continuous or nearly continuous abdominal pain for 6 months or more.

The reliability, validity, and clinical relevance of these criteria have not been demonstrated. Some children with RAP do not meet any criteria for a specific functional GI disorder.

Gut-brain connections. RAP may be associated with a heightened sensitivity to visceral sensations (visceral hyperalgesia) and a low pressure-pain threshold, leading to speculation that these children are hypersensitive to pain.