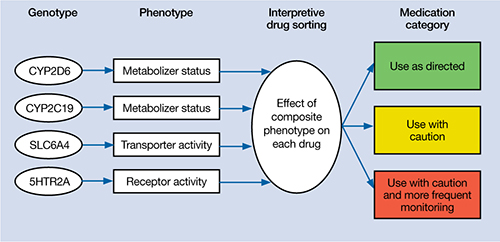

Figure

Genotype-phenotype integration into Mrs. C’s interpretive report

Table 2

Mrs. C’s pharmacogenomic-based interpretive report

| Use as directed | Use with caution | Use with caution and more frequent monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Antidepressants: Duloxetine, mirtazapine Antipsychotics: Clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone | Antidepressants: Amitriptyline,a,b bupropion,a citalopram,c clomipramine,a,b desipramine,a,b escitalopram,c fluoxetine,a fluvoxamine,c imipramine,a,b nortriptyline,a,b sertraline,c paroxetine,c trazodone,a venlafaxinea Antipsychotics: Aripiprazole,a haloperidol,a perphenazine,a risperidonea | None |

| aSerum level may be too high, lower doses may be required bSerum levels may be outside of optimal range cGenotype suggests less than optimal response | ||

The authors’ observations

Mrs. C’s genotype might explain some sensitivity to medications metabolized by CYP2D6 (eg, venlafaxine, paroxetine, fluoxetine), but does not explain her acute sensitivity to all of the medications she has taken. For example, she is an extensive metabolizer for CYP2C19, which metabolizes escitalopram; therefore, it is unlikely escitalopram, 2.5 mg/d, would result in high blood levels and side effects.3 Regardless of the next step in treatment, we deemed her somatic obsessions to be the most important clinical issue. It seems unlikely that Mrs. C would adhere to any medication regimen until this underlying problem was addressed.

The focus of treatment shifted to Mrs. C’s obsessions about her medications and their side effects. Mrs. C was fixated on the content of her obsessions (eg, medications, side effects) rather than the process of her obsessional thinking. The goal was to help Mrs. C identify, label, and ultimately create distance from her obsessive thoughts associated with side effects. The treatment team employed an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) model of observing and defusing thoughts in the inpatient setting (Table 3).4 ACT is based on mindfulness and committed, values-based action.5 When patients are “fused” with their thoughts, they believe these thoughts are important and representative of reality. In Mrs. C’s case, she fused with the concept that her medications were making her sick and the idea that she may have BD. The treatment team thought these fused thoughts were the major problem that resulted in 10 months of protracted illness.

Conversely, in a “defused” state, patients can separate from their thoughts and observe them as disparate sounds, words, stories, or bits of language. The goal is to observe and allow the patient’s thoughts to simply be thoughts rather than trying to determine if they are “true.” Mrs. C was fused with the idea that her medications were making her ill, so this belief became the story underlying her obsessional thinking. Helping her disengage from this story became the focus of her treatment.

Table 3

6 core principles of acceptance and commitment therapy

| Defusion | Learning to step back and observe thoughts as separate from the self |

| Acceptance | Allowing unpleasant thoughts to come and go without trying to control them |

| Contact with the present moment | Full awareness and engagement with present experiences |

| Observing the present self | Accessing a transcendent sense of self |

| Values | Clarifying what is most important to the patient |

| Committed action | Setting goals and taking action to achieve them |

| Source: Reference 4 | |

Results guide pharmacotherapy

In addition to helping change the focus of Mrs. C’s psychotherapy, we used the pharmacogenomic results to guide medication treatment. We initially prescribed fluvoxamine, 50 mg/d, because her partially compromised CYP2D6 pathway probably would play only a minor role in metabolizing the drug.1 Smoking induces CYP1A2, which is fluvoxamine’s primary metabolic pathway; however, Mrs. C does not smoke.6 When we saw Mrs. C in January 2009, the author (JGW) was unaware of any available genetic testing for CYP1A2, although now such testing is clinically available.

Mirtazapine is in the “use as directed” category for Mrs. C’s genotype (Table 2) and was the only medication she had adhered to at a therapeutic dose for more than a few days. However, she indicated that she would not adhere to this medication if we prescribed it again. Duloxetine also is in the “use as directed” category; however, given the entire clinical picture, we chose fluvoxamine because of Mrs. C’s obsessive symptomatology and because she had never reached a therapeutic dose of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

OUTCOME: Obsessions abate

Given Mrs. C’s lack of insight, we initiate a family approach to help broach the topic of obsessions as the focus of treatment. With her husband’s help, she participates in defusion techniques as an inpatient and follows up with an acceptance-based psychotherapist after discharge. After we share the pharmacogenomic information with Mrs. C, she agrees to try fluvoxamine, which is titrated to 100 mg/d. She maintains this dose at her 4-week follow-up visit. Notably, this was only the second time Mrs. C adhered to a medication trial since illness onset. Upon admission, Mrs. C had an HRSD-17 score of 30, indicating severe depression; at 4 weeks, her HRSD-17 score is 8, indicating mild depression.