The therapeutic consequences can be depressing!

A study published recently found a difference in brain blood flow between unipolar depression, also known as major depressive disorder (MDD), and the depressive phase of bipolar I (BD I) and bipolar II (BD II) disorders, known as bipolar depression.1 Researchers performed arterial spin labeling and submitted the resulting data to pattern recognition analysis to correctly classify 81% of subjects. This type of investigation augurs that objective biomarkers might halt the unrelenting misdiagnosis of bipolar depression as MDD and end the iatrogenic suffering of millions of bipolar disorder patients who became victims of a “therapeutic misadventure.”

It is perplexing that this problem has festered so long, simply because the two types of depression look deceptively alike.

This takes me back to my days in residency

Although I trained in one of the top psychiatry programs at the time, I was never taught that I must first classify my depressed patient as unipolar or bipolar before embarking on a treatment plan. Back then, “depression was depression” and treatment was the same for all depressed patients: Start with a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA). If there is no response within a few weeks, consider a different TCA or move to a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. If that does not work, perform electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Quite a few depressed patients actually worsened on antidepressant drugs, becoming agitated, irritable, and angry—yet clinicians did not recognize that change as a switch to irritable mania or hypomania, or a mixed depressed state. In fact, in those days, patients suffering mania or hypomania were expected to be euphoric and expansive, and the fact that almost one-half of bipolar mania presents with irritable, rather than euphoric, mood was not widely recognized, either.

I recall psychodynamic discussions as a resident about the anger and hostility that some patients with depression manifest. It was not widely recognized that treating bipolar depression with an antidepressant might lead to any of four undesirable switches: mania, hypomania, mixed state, or rapid cycling. We saw patients with all of these complications and simply labeled their condition “treatment-resistant depression,” especially if the patient switched to rapid cycling with recurrent depressions (which often happens with BD II patients who receive antidepressant monotherapy).

Frankly, BD II was not on our radar screen, and practically all such patients were given a misdiagnosis of MDD. No wonder we all marveled at how ECT finally helped out the so-called treatment-resistant patients!

Sadly, the state of the art treatment of bipolar depression back then was actually a state of incomplete knowledge. Okay—call it a state of ignorance wrapped in good intentions.

The dots did not get connected…

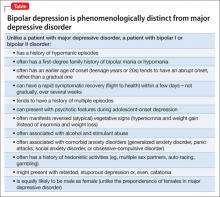

There were phenomenologic clues that, had we noticed them, could have corrected our clinical blind spot about the ways bipolar depression is different from unipolar depression. Yet we did not connect the dots about how bipolar depression is different from MDD (Table).

Treatment clues also should have opened our eyes to the different types of depression:

Clue #1: Patients with treatment-resistant depression often responded when lithium was added to an antidepressant. This led to the belief that lithium has antidepressant properties, instead of clueing us that treatment-resistant depression is actually a bipolar type of depression.

Clue #2: Likewise, patients with treatment-resistant depression improved when an antipsychotic agent, which is also anti-manic, was added to an antidepressant (seasoned clinicians might remember the amitriptyline-perphenazine combination pill, sold as Triavil, that was a precursor of the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination developed a few years ago to treat bipolar depression).

Clue #3: ECT exerted efficacy in patients who failed an antidepressant or who got worse taking one (ie, switched to a mixed state).

A new age of therapeutics

In the past few years, we’ve witnessed the development of several pharmacotherapeutic agents for bipolar depression. First, the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination was approved for this indication in 2003. That was followed by quetiapine monotherapy in 2005 and, most recently, in 2013, lurasidone (both as monotherapy and as an adjunct to a mood stabilizer).

With those three FDA-approved options for bipolar depression, clinicians can now treat this type of depression without putting the patient at risk of complications that ensue when antidepressants approved only for MDD are used erroneously as monotherapy for bipolar depression.

These days, psychiatry residents are rigorously trained to differentiate unipolar and bipolar depression and to select the most appropriate, evidence-based treatment for bipolar depression. The state of ignorance surrounding this psychiatric condition is lifting, although there are pockets of persisting nonrecognition in some settings. Gaps in knowledge underpin and perpetuate hoary practices, but innovative research—such as the study cited here on brain blood-flow biomarkers—is the ultimate antidote to ignorance.