Mr. M, age 28, was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia 6 years ago after experiencing a psychotic break involving auditory hallucinations and paranoia. Olanzapine, 10 mg/d, relieved his symptoms, but he stopped taking the drug after gaining 40 pounds and developing diabetes mellitus. He had 2 other hospital admissions for acute psychosis and has taken at least 1 other medication, the name of which he can’t recall. Recently, Mr. M was involuntarily admitted to the psychiatric ward of his local hospital. His psychiatrist started aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, which was titrated to 30 mg/d. After 2 weeks he reports only a slight decrease in hallucinations. His mother is growing concerned about the effectiveness of this medication and wants to know if it’s time to consider another drug.

Time to onset of action of antipsychotic agents has been debated since at least 1970.1 Supporters of the delayed-onset hypothesis assert that antipsychotics take weeks or months to show significant improvement of symptoms because of the need for depolarization block for efficacy.2 Trials of 4 to 6 weeks often are recommended for patients before failure is declared,3,4 and trials of this length or longer have proved useful for first-episode patients.5-7 Recent studies suggest, however, that response is cumulative for chronically ill

• Chronically ill and first-episode patients may respond differently to antipsychotics.

• In chronically ill patients with schizophrenia, early non-response accurately predicts non-response at weeks 4 to 12 in 75% to 85% of patients. Early response accurately predicts sustained response at weeks 4 to 12 in approximately 50% to 70% of patients.

• In first-episode patients with schizophrenia, early non-response predicts non-response at weeks 12 to 16 in approximately 60% to 65% of patients. Early response predicts response at weeks 12 to 16 in approximately 60% to 75% of patients.triglyceride, and LDL levels, and a decrease in the HDL level.2 These effects may be seen without an increase in BMI, and should be considered a direct effect of the antipsychotic.5 Although the mechanism by which dyslipidemia occurs is poorly understood, an increase in the blood glucose level is thought to be, in part, mediated by antagonism of M3 muscarinic receptors on pancreatic âpatients with most improvement occurring during weeks 1 and 2.1,8

Two meta-analyses found the greatest rate of cumulative improvement in symptoms during the first 2 weeks.1,8 These analyses included chronically ill patients with mean duration of illness of 15.5 and 10.4 years, respectively. Patients reported 21.9% and 20.5% reductions in symptoms from baseline at 2 weeks, with total responses between 30% at 4 weeks and 40% at 1 year, respectively. These meta-analyses indicate that most of the benefit from antipsychotics in this patient population occurs in the first 2 weeks, which supports the early-response hypothesis.

These observations led to questions about the predictive value of early response and minimum time to determine treatment failure. This article discusses the significance of early response and non-response to antipsychotics and their impact on treating patients with schizophrenia.

What are the predictive factors? How can they guide treatment?

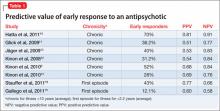

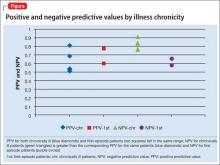

Of the 8 studies in our literature review, only 2 reported early response rates >50%.9,10 (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a Box describing the literature review.) Positive predictive value (PPV) ranged from 0.51 to 0.81, meaning that 51% to 81% of early responders continued to respond. Six of the 8 studies reported PPV of 50% to 70%. 9,11-15 This appears to be true for chronic and first-episode patients, suggesting that 30% to 50% of early responders will fail to have a sustained response (Table 1,9-16Table 2,9-16 and Figure).

Compared with early response, early non-response is a more consistent predictor of final non-response. In every study of chronically ill patients, negative predictive value (NPV) was greater than PPV (Table 1).9-16 NPVs in the literature suggest that 58% to 91% of early non-responders will continue to be non-responders. This seems to be true of chronically ill patients for whom NPVs consistently were between 75% and 85%. By comparison, in first-episode patients NPVs of 58% and 66% were calculated (Table 19-16 and Figure).14,15

These observations suggest that reassessing drug therapy is indicated early in treatment for early non-responders, particularly in chronically ill patients. However, early non-response in a first-episode patient is not as strong a predictor of eventual treatment failure, supporting the idea that first-episode patients may experience a delayed response to therapy. Researchers studying onset of antipsychotic effect report that median time to response onset in first-episode patients may be ≥8 weeks.6,8 In patients who do not achieve modest early response, assess dose, adherence, substance abuse, and psychosocial stressors.3 For patients without dose, adherence, substance use, or stress issues, switching drug therapy in chronically ill early non-responders is reasonable because the probability of a late response is small.