Ms. K, age 35, soon will deliver her second child. She has a 12-year history of bipolar disorder, which was well controlled with lithium, 1,200 mg/d. During her first pregnancy 3 years ago, Ms. K stopped taking lithium because she was concerned about the risk of Ebstein’s anomaly. She experienced a bipolar relapse after her healthy baby was born, and developed postpartum psychosis that was treated by restarting lithium, 1,200 mg/d, and adding olanzapine, 10 mg/d.

Ms. K has continued these medications throughout her current pregnancy. She wants to breast-feed her infant and is concerned about the effects that psychotropics might have on her newborn.

Breast-feeding and medications

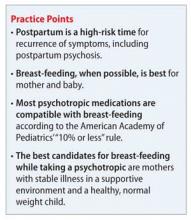

The benefits of breast-feeding for mother and infant are well-known. Despite this, some women with bipolar disorder are advised not to breast-feed or, worse, to discontinue their medications in order to breast-feed. Decisions about breast-feeding while taking medications should be based on evidence of benefits and risks to the infant, along with a discussion of the risks of untreated illness, which is high postpartum. The prescribing information for many of the medications used to treat bipolar disorder advise against breast-feeding, although there is little evidence of harm.

Drug dosages and levels in breast milk can be reported a few different ways:

• percentage of maternal dosage measured in the breast milk

• percentage weight-adjusted maternal dosage

• percentage of maternal plasma level, and milk-to-plasma ratio (M:P).

Daily infant dosage can be calculated by multiplying the average concentration of the drug in breast milk (mg/mL) by the average volume of milk the baby ingests in 24 hours (usually 150 mL).1 The relative infant dosage can be calculated as the percentage maternal dosage, which is the daily infant dosage (mg/kg/d) ÷ maternal dosage (mg/kg/d) × 100.1

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, ≤10% of the maternal dosage is compatible with breast-feeding.1 Most psychotropics studied fall below this threshold. Keep in mind that all published research is for breast-feeding a full-term infant; exercise caution with premature or low birth weight infants. Infants born to mothers taking a psychotropic should be monitored for withdrawal symptoms, which might be associated with antidepressants and benzodiazepines, but otherwise are rare.

Lithium

Breast-feeding during lithium treatment has been considered contraindicated based on early reports that lithium was highly excreted in breast milk.2 A 2003 study2 of 11 women found that lithium was excreted in breast milk in amounts between zero and 30% of maternal dosage (mean, 12.2% ± 8.5%; median, 11.2%; 95% CI, 6.3% to 18.0%). Researchers measured serum concentrations in 2 infants and found that 1 received 17% to 20% of the maternal dosage, and the other showed 50%. None of the infants experienced adverse events. In a study of 10 mother-infant pairs, breast milk lithium concentration averaged 0.35 mEq/L (standard deviation [SD] = 0.10, range 0.19 to 0.48 mEq/L), with paired infant serum concentrations of 0.16 mEq/L (SD = 0.06, range 0.09 to 0.25 mEq/L).3 Some transient abnormalities were found in infant serum concentrations of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine; there were no adverse effects on development. The authors recommend monitoring for TSH abnormalities in infants.

Olanzapine

Olanzapine prescribing information cites a study reporting that 1.8% of the maternal dosage is transferred to breast milk.4 Yet the olanzapine prescribing information states, “It is recommended that women receiving olanzapine should not breast-feed.” Olanzapine use during breast-feeding has been studied more than many medications, in part because of a database maintained by the manufacturer. In a study using the manufacturer’s database (N = 102) adverse reactions were reported in 15.6% of the infants, with the most common being somnolence (3.9%), irritability (2%), tremor (2%), and insomnia (2%).5

Other second-generation antipsychotics

Aripiprazole. The only case report of aripiprazole excretion in human breast milk found a concentration of approximately 20% of the maternal plasma level and an M:P ratio of 0.18:0.2.6

Asenapine. According to asenapine prescribing information7 and a literature search, it is not known whether asenapine is excreted in breast milk of humans, although it is found in the milk of lactating rats.

Lurasidone. According to the lurasidone prescribing information8 and a literature search, it is not known whether lurasidone is excreted in human breast milk, although it is found in the milk of lactating rats.

Quetiapine. An initial study reported that 0.09% to 0.43% of the maternal dosage of quetiapine was excreted in breast milk.9 Further studies found excretion to be 0.09% of maternal dosage, with infant plasma levels reaching 6% of the maternal dosage.10 A case series found that one-third of babies exposed to quetiapine during breast-feeding showed some neurodevelopmental delay, although these mothers also were taking other psychotropics.11