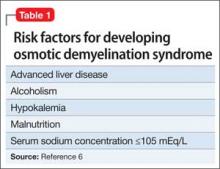

Evidence suggests, however, that this 1-day limit might be too high for some patients. Alcoholism, hypokalemia, malnutrition, and liver disease are present in a high percentage of patients who develop

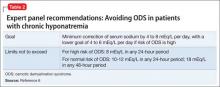

ODS after correcting hyponatremia (Table 1).6 Therefore, for patients such as Mr. W who are at high risk of ODS, experts recommend a goal of 4 to 6 mEq/L/d with a correction rate of ≤8 mEq/L in any 24-hour period (Table 2).6

TREATMENT Sodium normalizes

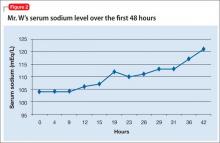

Mr. W receives 1 L of normal saline in the ED before admission to the MICU. Once in the MICU, despite likely chronic hyponatremia, he receives hypertonic (3%) saline, followed by normal saline. Initially, he responds when the serum sodium concentration improves. Because of his likely SIADH, Mr. W is fluid-restricted for 4 days. Serum sodium returns to normal over 7 hospital days (Figure 2). To address the profound hypokalemia, Mr. S receives 30 mEq of potassium chloride in the ED, and potassium is repeated daily throughout his stay in the MICU.

Mr. W remains lethargic, with intermittent periods of confusion throughout the hospital stay. His altered mental status is attributed to hepatic encephalopathy secondary to alcoholic hepatitis. The Maddrey discriminant function is a calculation that stratifies patients with alcoholic hepatitis for risk of mortality and the use of steroids. Because Mr. W shows a Maddrey discriminant function ≥32, he receives methylprednisolone, followed by pentoxifylline, and liver function tests trend down. He also receives lactulose throughout hospitalization.

By discharge on hospital day 9, Mr. W’s serum sodium is 138 mEq/L; serum potassium, 4.1 mEq/L. Total bilirubin and prothrombin remain elevated. Mr. W is discharged on lactulose, thiamine, folic acid, and a 1-month course of pentoxifylline, 400 mg, 3 times a day.

READMISSION Unsteady gait, nausea

Three days after discharge, Mr. W returns to the ED after experiencing a 20-second episode of total body rigidity. He has an unsteady gait and worsening nausea and vomiting.

When Mr. W arrives in the ED, he confirms he is taking his discharge medications as prescribed. His parents report that he has consumed alcohol and Cannabis since discharge and has been taking his sibling’s prescription medications, including quetiapine.

In the ED, Mr. W is awake, alert, and oriented to person, place, and time. Vital signs are: pulse, 118 beats per minute; blood pressure, 128/73 mm Hg; respirations, 16 breaths per minute; and temperature, 98.5ºF. Physical examination, again, is notable for scleral icterus, jaundice, and asterixis. No focal neurologic deficits are noted.

Consistent with Mr. W’s previous admission, laboratory values reveal altered hepatic function and impaired coagulation. The serum sodium level remains within normal limits at 136 mEq/L. However, again, metabolic disturbances include decreased chloride (97 mEq/L), potassium (2.9 mEq/L), and CO2 (18.2 mEq/L). CT on readmission is unchanged from the earlier hospitalization.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. W’s total body rigidity?

a) seizure

b) ODS

c) drug intoxication

d) neuroleptic malignant syndrome

EVALUATION Shaking and weakness

Once admitted to the hospital, Mr. W reports an episode of right upper-extremity “shaking,” followed by weakness. He remembers the entire event and denies tongue biting or incontinence. He is evaluated for possible seizure, given his multiple risk factors, including drug and alcohol use, ingestion of quetiapine, and history of hyponatremia. Routine EEG is negative but prolactin level is elevated.

Mr. W’s mental status continues to wax and wane, prompting a neurology consult and MRI for further evaluation. MRI of the brain without contrast reveals restricted diffusion in the pons centrally, with extension bilaterally to the midbrain and thalami—findings consistent with central pontine myelinolysis. A neurology consultation reveals quadriparesis, paraparesis, dysarthria, and diplopia on examination, all symptoms associated with central pontine myelinolysis.

The authors’ observations

ODS, including central and extrapontine myelinolysis, is a demyelinating condition that occurs because of severe osmotic stress, most commonly secondary to the overly rapid correction of hyponatremia in patients with conditions leading to nutritional or electrolyte stress.7 Mr. W is considered at high risk of developing ODS because he fulfills the 5 criteria listed in Table 1.

Several psychiatric illnesses and neuropsychiatric medications could lead to hyponatremia. Many studies8-10 have documented hyponatremia and resulting ODS in patients with alcoholism, schizophrenia, anorexia, primary psychogenic polydipsia, and MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) abuse. Hyponatremia is a side effect of several neuropsychiatric medications, including serotonin reuptake inhibitors, lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, opioids, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and antipsychotic polypharmacy. Other commonly used medications associated with hyponatremia include salt-losing diuretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen.7

Disease severity varies from asymptomatic to coma or death. Symptoms, although some could reverse completely, typically are a combination of neuropsychiatric (ie, emotional lability, disinhibition, and other bizarre behaviors) and neurologic. Neurologic symptoms include confusion, impaired cognition, dysarthria, dysphagia, gait instability, weakness or paralysis, and generalized seizures. Severely affected patients could experience “locked-in syndrome,” in which they are awake but unable to move or communicate. Also consistent with Mr. W’s case, ODS often presents initially with delirium, seizures, or encephalopathy, followed by a lucid interval before symptoms develop.7