User login

Modifier -25 and the New 2021 E/M Codes: Documentation of Separate and Distinct Just Got Easier

Insurers Target Modifier -25

Modifier -25 allows reporting of both a minor procedure (ie, one with a 0- or 10-day global period) and a separate and distinct evaluation and management (E/M) service on the same date of service.1 Because of the multicomplaint nature of dermatology, the ability to report a same-day procedure and an E/M service is critical for efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centered dermatologic care. However, it is well known that the use of modifier -25 has been under notable insurer scrutiny and is a common reason for medical record audits.2,3 Some insurers have responded to increased utilization of modifier -25 by cutting reimbursement for claims that include both a procedure and an E/M service or by denying one of the services altogether.4-6 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also have expressed concern about this coding combination with proposed cuts to reimbursement.7 Moreover, the Office of Inspector General has announced a work plan to investigate the frequent utilization of E/M codes and minor procedures by dermatologists.8 Clearly, modifier -25 is a continued target by insurers and regulators; therefore, dermatologists will want to make sure their coding and documentation meet all requirements and are updated for the new E/M codes for 2021.

The American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology indicates that modifier -25 allows reporting of a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of a procedure or other service.”1 Given that dermatology patients typically present with multiple concerns, dermatologists commonly evaluate and treat numerous conditions during one visit. Understanding what constitutes a separately identifiable E/M service is critical to bill accurately and to pass insurer audits.

Global Surgical Package

To appropriately bill both a procedure and an E/M service, the physician must indicate that the patient’s condition required an E/M service above and beyond the usual work of the procedure. The compilation of evaluation and work included in the payment for a procedure is called the global surgical package.9 In general, the global surgical package includes local or topical anesthesia; the surgical service/procedure itself; immediate postoperative care, including dictating the operative note; meeting/discussing the patient’s procedure with family and other physicians; and writing orders for the patient. For minor procedures (ie, those with either 0- or 10-day global periods), the surgical package also includes same-day E/M services associated with the decision to perform surgery. An appropriate history and physical examination as well as a discussion of the differential diagnosis, treatment options, and risk and benefits of treatment are all included in the payment of a minor procedure itself. Therefore, an evaluation to discuss a patient’s condition or change in condition, alternatives to treatment, or next steps after a diagnosis related to a treatment or diagnostic procedure should not be separately reported. Moreover, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not in itself sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M service with these minor procedures. For major procedures (ie, those with 90-day postoperative periods), the decision for surgery is excluded from the global surgical package.

2021 E/M Codes Simplify Documentation

The biggest coding change of 2021 was the new E/M codes.10 Prior to this year, the descriptors of E/M services recognized 7 components to define the levels of E/M services11: history and nature of the presenting problem; physical examination; medical decision-making (MDM); counseling; coordination of care; and time. Furthermore, history, physical examination, and MDM were all broken down into more granular elements that were summed to determine the level for each component; for example, the history of the presenting problem was defined as a chronological description of the development of the patient’s present illness, including the following elements: location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms. Each of these categories would constitute bullet points to be summed to determine the level of history. Physical examination and MDM bullet points also would be summed to determine a proper coding level.11 Understandably, this coding scheme was complicated and burdensome to medical providers.

The redefinition of the E/M codes for 2021 substantially simplified the determination of coding level and documentation.10 The revisions to the E/M office visit code descriptors and documentation standards are now centered around how physicians think and take care of patients and not on mandatory standards and checking boxes. The main changes involve MDM as the prime determinant of the coding level. Elements of MDM affecting coding for an outpatient or office visit now include only 3 components: the number and complexity of problems addressed in the encounter, the amount or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and the risk of complications or morbidity of patient management. Gone are the requirements from the earlier criteria requiring so many bullet points for the history, physical examination, and MDM.

Dermatologists may ask, “How does the new E/M coding structure affect reporting and documenting an E/M and a procedure on the same day?” The answer is that the determination of separate and distinct is basically unchanged with the new E/M codes; however, the documentation requirements for modifier -25 using the new E/M codes are simplified.

As always, the key to determining whether a separate and distinct E/M service was provided and subsequently documented is to deconstruct the medical note. All evaluation services associated with the procedure—making a clinical diagnosis or differential diagnosis, decision to perform surgery, and discussion of alternative treatments—should be removed from one’s documentation as shown in the example below. If a complete E/M service still exists, then an E/M may be billed in addition to the procedure. Physical examination of the treatment area is included in the surgical package. With the prior E/M criteria, physical examination of the procedural area could not be used again as a bullet point to count for the E/M level. However, with the new 2021 coding requirements, the documentation of a separate MDM will be sufficient to meet criteria because documentation of physical examination is not a requirement.

Modifier -25 Examples

Let’s examine a typical dermatologist medical note. An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. The patient also complains of a growing tender lesion on the left elbow of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination reveals a linear vesicular eruption on the left wrist and a tender hyperkeratotic papule on the left elbow. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed. The decision is made to perform a tangential biopsy of the lesion on the left elbow because of the suspicion for malignancy. The biopsy is performed the same day.

This case clearly illustrates performance of an E/M service in the treatment of rhus dermatitis, which is separate and distinct from the biopsy procedure; however, in evaluating whether the case meets the documentation requirements for modifier -25, the information in the medical note inclusive to the procedure’s global surgical package, including history associated with establishing the diagnosis, physical examination of the procedure area(s), and discussion of treatment options, is eliminated, leaving the following notes: An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed.

Because the physical examination of the body part (left arm) is included in the procedure’s global surgical package, the examination of the left wrist cannot be used as coding support for the E/M service. This makes a difference for coding level in the prior E/M coding requirements, which required examination bullet points. However, with the 2021 E/M codes, documentation of physical examination bullet points is irrelevant to the coding level. Therefore, qualifying for a modifier -25 claim is more straightforward in this case with the new code set. Because bullet points are not integral to the 2021 E/M codes, qualifying and properly documenting for a higher level of service will likely be more common in dermatology.

Final Thoughts

Frequent use of modifier -25 is a critical part of a high-quality and cost-effective dermatology practice. Same-day performance of minor procedures and E/M services allows for more rapid and efficient diagnosis and treatment of various conditions as well as minimizing unnecessary office visits. The new E/M codes for 2021 actually make the documentation of a separate and distinct E/M service less complicated because the bullet point requirements associated with the old E/M codes have been eliminated. Understanding how the new E/M code descriptors affect modifier -25 reporting and clear documentation of separate, distinct, and medically necessary E/M services will be needed due to increased insurer scrutiny and audits.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2021, Professional Edition. American Medical Association; 2020.

- Rogers HW. Modifier −25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- Rogers HW. One diagnosis and modifier −25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Update regarding E/M with modifier −25—professional. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield website. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://providernews.anthem.com/ohio/article/update-regarding-em-with-modifier-25-professional

- Payment policies—surgery. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care website. Updated May 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/provider/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/07/H-6-Surgery-PM.pdf

- Modifier 25: frequently asked questions. Independence Blue Cross website. Updated September 25, 2017. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://provcomm.ibx.com/ibc/archive/pages/A86603B03881756B8525817E00768006.aspx

- Huang G. CMS 2019 fee schedule takes modifier 25 cuts, runs with them. Doctors Management website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.doctors-management.com/cms-2019-feeschedule-modifier25/

- Dermatologist claims for evaluation and management services on the same day as minor surgical procedures. US Department of Health and Humans Services Office of Inspector General website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000577.asp

- Global surgery booklet. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Updated September 2018. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/globallsurgery-icn907166.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M)—office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

- 1997 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf

Insurers Target Modifier -25

Modifier -25 allows reporting of both a minor procedure (ie, one with a 0- or 10-day global period) and a separate and distinct evaluation and management (E/M) service on the same date of service.1 Because of the multicomplaint nature of dermatology, the ability to report a same-day procedure and an E/M service is critical for efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centered dermatologic care. However, it is well known that the use of modifier -25 has been under notable insurer scrutiny and is a common reason for medical record audits.2,3 Some insurers have responded to increased utilization of modifier -25 by cutting reimbursement for claims that include both a procedure and an E/M service or by denying one of the services altogether.4-6 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also have expressed concern about this coding combination with proposed cuts to reimbursement.7 Moreover, the Office of Inspector General has announced a work plan to investigate the frequent utilization of E/M codes and minor procedures by dermatologists.8 Clearly, modifier -25 is a continued target by insurers and regulators; therefore, dermatologists will want to make sure their coding and documentation meet all requirements and are updated for the new E/M codes for 2021.

The American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology indicates that modifier -25 allows reporting of a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of a procedure or other service.”1 Given that dermatology patients typically present with multiple concerns, dermatologists commonly evaluate and treat numerous conditions during one visit. Understanding what constitutes a separately identifiable E/M service is critical to bill accurately and to pass insurer audits.

Global Surgical Package

To appropriately bill both a procedure and an E/M service, the physician must indicate that the patient’s condition required an E/M service above and beyond the usual work of the procedure. The compilation of evaluation and work included in the payment for a procedure is called the global surgical package.9 In general, the global surgical package includes local or topical anesthesia; the surgical service/procedure itself; immediate postoperative care, including dictating the operative note; meeting/discussing the patient’s procedure with family and other physicians; and writing orders for the patient. For minor procedures (ie, those with either 0- or 10-day global periods), the surgical package also includes same-day E/M services associated with the decision to perform surgery. An appropriate history and physical examination as well as a discussion of the differential diagnosis, treatment options, and risk and benefits of treatment are all included in the payment of a minor procedure itself. Therefore, an evaluation to discuss a patient’s condition or change in condition, alternatives to treatment, or next steps after a diagnosis related to a treatment or diagnostic procedure should not be separately reported. Moreover, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not in itself sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M service with these minor procedures. For major procedures (ie, those with 90-day postoperative periods), the decision for surgery is excluded from the global surgical package.

2021 E/M Codes Simplify Documentation

The biggest coding change of 2021 was the new E/M codes.10 Prior to this year, the descriptors of E/M services recognized 7 components to define the levels of E/M services11: history and nature of the presenting problem; physical examination; medical decision-making (MDM); counseling; coordination of care; and time. Furthermore, history, physical examination, and MDM were all broken down into more granular elements that were summed to determine the level for each component; for example, the history of the presenting problem was defined as a chronological description of the development of the patient’s present illness, including the following elements: location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms. Each of these categories would constitute bullet points to be summed to determine the level of history. Physical examination and MDM bullet points also would be summed to determine a proper coding level.11 Understandably, this coding scheme was complicated and burdensome to medical providers.

The redefinition of the E/M codes for 2021 substantially simplified the determination of coding level and documentation.10 The revisions to the E/M office visit code descriptors and documentation standards are now centered around how physicians think and take care of patients and not on mandatory standards and checking boxes. The main changes involve MDM as the prime determinant of the coding level. Elements of MDM affecting coding for an outpatient or office visit now include only 3 components: the number and complexity of problems addressed in the encounter, the amount or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and the risk of complications or morbidity of patient management. Gone are the requirements from the earlier criteria requiring so many bullet points for the history, physical examination, and MDM.

Dermatologists may ask, “How does the new E/M coding structure affect reporting and documenting an E/M and a procedure on the same day?” The answer is that the determination of separate and distinct is basically unchanged with the new E/M codes; however, the documentation requirements for modifier -25 using the new E/M codes are simplified.

As always, the key to determining whether a separate and distinct E/M service was provided and subsequently documented is to deconstruct the medical note. All evaluation services associated with the procedure—making a clinical diagnosis or differential diagnosis, decision to perform surgery, and discussion of alternative treatments—should be removed from one’s documentation as shown in the example below. If a complete E/M service still exists, then an E/M may be billed in addition to the procedure. Physical examination of the treatment area is included in the surgical package. With the prior E/M criteria, physical examination of the procedural area could not be used again as a bullet point to count for the E/M level. However, with the new 2021 coding requirements, the documentation of a separate MDM will be sufficient to meet criteria because documentation of physical examination is not a requirement.

Modifier -25 Examples

Let’s examine a typical dermatologist medical note. An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. The patient also complains of a growing tender lesion on the left elbow of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination reveals a linear vesicular eruption on the left wrist and a tender hyperkeratotic papule on the left elbow. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed. The decision is made to perform a tangential biopsy of the lesion on the left elbow because of the suspicion for malignancy. The biopsy is performed the same day.

This case clearly illustrates performance of an E/M service in the treatment of rhus dermatitis, which is separate and distinct from the biopsy procedure; however, in evaluating whether the case meets the documentation requirements for modifier -25, the information in the medical note inclusive to the procedure’s global surgical package, including history associated with establishing the diagnosis, physical examination of the procedure area(s), and discussion of treatment options, is eliminated, leaving the following notes: An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed.

Because the physical examination of the body part (left arm) is included in the procedure’s global surgical package, the examination of the left wrist cannot be used as coding support for the E/M service. This makes a difference for coding level in the prior E/M coding requirements, which required examination bullet points. However, with the 2021 E/M codes, documentation of physical examination bullet points is irrelevant to the coding level. Therefore, qualifying for a modifier -25 claim is more straightforward in this case with the new code set. Because bullet points are not integral to the 2021 E/M codes, qualifying and properly documenting for a higher level of service will likely be more common in dermatology.

Final Thoughts

Frequent use of modifier -25 is a critical part of a high-quality and cost-effective dermatology practice. Same-day performance of minor procedures and E/M services allows for more rapid and efficient diagnosis and treatment of various conditions as well as minimizing unnecessary office visits. The new E/M codes for 2021 actually make the documentation of a separate and distinct E/M service less complicated because the bullet point requirements associated with the old E/M codes have been eliminated. Understanding how the new E/M code descriptors affect modifier -25 reporting and clear documentation of separate, distinct, and medically necessary E/M services will be needed due to increased insurer scrutiny and audits.

Insurers Target Modifier -25

Modifier -25 allows reporting of both a minor procedure (ie, one with a 0- or 10-day global period) and a separate and distinct evaluation and management (E/M) service on the same date of service.1 Because of the multicomplaint nature of dermatology, the ability to report a same-day procedure and an E/M service is critical for efficient, cost-effective, and patient-centered dermatologic care. However, it is well known that the use of modifier -25 has been under notable insurer scrutiny and is a common reason for medical record audits.2,3 Some insurers have responded to increased utilization of modifier -25 by cutting reimbursement for claims that include both a procedure and an E/M service or by denying one of the services altogether.4-6 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services also have expressed concern about this coding combination with proposed cuts to reimbursement.7 Moreover, the Office of Inspector General has announced a work plan to investigate the frequent utilization of E/M codes and minor procedures by dermatologists.8 Clearly, modifier -25 is a continued target by insurers and regulators; therefore, dermatologists will want to make sure their coding and documentation meet all requirements and are updated for the new E/M codes for 2021.

The American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology indicates that modifier -25 allows reporting of a “significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician or other qualified health care professional on the same day of a procedure or other service.”1 Given that dermatology patients typically present with multiple concerns, dermatologists commonly evaluate and treat numerous conditions during one visit. Understanding what constitutes a separately identifiable E/M service is critical to bill accurately and to pass insurer audits.

Global Surgical Package

To appropriately bill both a procedure and an E/M service, the physician must indicate that the patient’s condition required an E/M service above and beyond the usual work of the procedure. The compilation of evaluation and work included in the payment for a procedure is called the global surgical package.9 In general, the global surgical package includes local or topical anesthesia; the surgical service/procedure itself; immediate postoperative care, including dictating the operative note; meeting/discussing the patient’s procedure with family and other physicians; and writing orders for the patient. For minor procedures (ie, those with either 0- or 10-day global periods), the surgical package also includes same-day E/M services associated with the decision to perform surgery. An appropriate history and physical examination as well as a discussion of the differential diagnosis, treatment options, and risk and benefits of treatment are all included in the payment of a minor procedure itself. Therefore, an evaluation to discuss a patient’s condition or change in condition, alternatives to treatment, or next steps after a diagnosis related to a treatment or diagnostic procedure should not be separately reported. Moreover, the fact that the patient is new to the physician is not in itself sufficient to allow reporting of an E/M service with these minor procedures. For major procedures (ie, those with 90-day postoperative periods), the decision for surgery is excluded from the global surgical package.

2021 E/M Codes Simplify Documentation

The biggest coding change of 2021 was the new E/M codes.10 Prior to this year, the descriptors of E/M services recognized 7 components to define the levels of E/M services11: history and nature of the presenting problem; physical examination; medical decision-making (MDM); counseling; coordination of care; and time. Furthermore, history, physical examination, and MDM were all broken down into more granular elements that were summed to determine the level for each component; for example, the history of the presenting problem was defined as a chronological description of the development of the patient’s present illness, including the following elements: location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms. Each of these categories would constitute bullet points to be summed to determine the level of history. Physical examination and MDM bullet points also would be summed to determine a proper coding level.11 Understandably, this coding scheme was complicated and burdensome to medical providers.

The redefinition of the E/M codes for 2021 substantially simplified the determination of coding level and documentation.10 The revisions to the E/M office visit code descriptors and documentation standards are now centered around how physicians think and take care of patients and not on mandatory standards and checking boxes. The main changes involve MDM as the prime determinant of the coding level. Elements of MDM affecting coding for an outpatient or office visit now include only 3 components: the number and complexity of problems addressed in the encounter, the amount or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and the risk of complications or morbidity of patient management. Gone are the requirements from the earlier criteria requiring so many bullet points for the history, physical examination, and MDM.

Dermatologists may ask, “How does the new E/M coding structure affect reporting and documenting an E/M and a procedure on the same day?” The answer is that the determination of separate and distinct is basically unchanged with the new E/M codes; however, the documentation requirements for modifier -25 using the new E/M codes are simplified.

As always, the key to determining whether a separate and distinct E/M service was provided and subsequently documented is to deconstruct the medical note. All evaluation services associated with the procedure—making a clinical diagnosis or differential diagnosis, decision to perform surgery, and discussion of alternative treatments—should be removed from one’s documentation as shown in the example below. If a complete E/M service still exists, then an E/M may be billed in addition to the procedure. Physical examination of the treatment area is included in the surgical package. With the prior E/M criteria, physical examination of the procedural area could not be used again as a bullet point to count for the E/M level. However, with the new 2021 coding requirements, the documentation of a separate MDM will be sufficient to meet criteria because documentation of physical examination is not a requirement.

Modifier -25 Examples

Let’s examine a typical dermatologist medical note. An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. The patient also complains of a growing tender lesion on the left elbow of 2 months’ duration. Physical examination reveals a linear vesicular eruption on the left wrist and a tender hyperkeratotic papule on the left elbow. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed. The decision is made to perform a tangential biopsy of the lesion on the left elbow because of the suspicion for malignancy. The biopsy is performed the same day.

This case clearly illustrates performance of an E/M service in the treatment of rhus dermatitis, which is separate and distinct from the biopsy procedure; however, in evaluating whether the case meets the documentation requirements for modifier -25, the information in the medical note inclusive to the procedure’s global surgical package, including history associated with establishing the diagnosis, physical examination of the procedure area(s), and discussion of treatment options, is eliminated, leaving the following notes: An established patient presents to the dermatologist complaining of an itchy rash on the left wrist after a hiking trip. Treatment with topical hydrocortisone 1% did not help. No data is evaluated. A diagnosis of acute rhus dermatitis of the left wrist is made, and betamethasone cream is prescribed.

Because the physical examination of the body part (left arm) is included in the procedure’s global surgical package, the examination of the left wrist cannot be used as coding support for the E/M service. This makes a difference for coding level in the prior E/M coding requirements, which required examination bullet points. However, with the 2021 E/M codes, documentation of physical examination bullet points is irrelevant to the coding level. Therefore, qualifying for a modifier -25 claim is more straightforward in this case with the new code set. Because bullet points are not integral to the 2021 E/M codes, qualifying and properly documenting for a higher level of service will likely be more common in dermatology.

Final Thoughts

Frequent use of modifier -25 is a critical part of a high-quality and cost-effective dermatology practice. Same-day performance of minor procedures and E/M services allows for more rapid and efficient diagnosis and treatment of various conditions as well as minimizing unnecessary office visits. The new E/M codes for 2021 actually make the documentation of a separate and distinct E/M service less complicated because the bullet point requirements associated with the old E/M codes have been eliminated. Understanding how the new E/M code descriptors affect modifier -25 reporting and clear documentation of separate, distinct, and medically necessary E/M services will be needed due to increased insurer scrutiny and audits.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2021, Professional Edition. American Medical Association; 2020.

- Rogers HW. Modifier −25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- Rogers HW. One diagnosis and modifier −25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Update regarding E/M with modifier −25—professional. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield website. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://providernews.anthem.com/ohio/article/update-regarding-em-with-modifier-25-professional

- Payment policies—surgery. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care website. Updated May 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/provider/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/07/H-6-Surgery-PM.pdf

- Modifier 25: frequently asked questions. Independence Blue Cross website. Updated September 25, 2017. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://provcomm.ibx.com/ibc/archive/pages/A86603B03881756B8525817E00768006.aspx

- Huang G. CMS 2019 fee schedule takes modifier 25 cuts, runs with them. Doctors Management website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.doctors-management.com/cms-2019-feeschedule-modifier25/

- Dermatologist claims for evaluation and management services on the same day as minor surgical procedures. US Department of Health and Humans Services Office of Inspector General website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000577.asp

- Global surgery booklet. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Updated September 2018. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/globallsurgery-icn907166.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M)—office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

- 1997 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf

- Current Procedural Terminology 2021, Professional Edition. American Medical Association; 2020.

- Rogers HW. Modifier −25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- Rogers HW. One diagnosis and modifier −25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Update regarding E/M with modifier −25—professional. Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield website. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://providernews.anthem.com/ohio/article/update-regarding-em-with-modifier-25-professional

- Payment policies—surgery. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care website. Updated May 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.harvardpilgrim.org/provider/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/07/H-6-Surgery-PM.pdf

- Modifier 25: frequently asked questions. Independence Blue Cross website. Updated September 25, 2017. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://provcomm.ibx.com/ibc/archive/pages/A86603B03881756B8525817E00768006.aspx

- Huang G. CMS 2019 fee schedule takes modifier 25 cuts, runs with them. Doctors Management website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.doctors-management.com/cms-2019-feeschedule-modifier25/

- Dermatologist claims for evaluation and management services on the same day as minor surgical procedures. US Department of Health and Humans Services Office of Inspector General website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000577.asp

- Global surgery booklet. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Updated September 2018. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/medicare-learning-network-mln/mlnproducts/downloads/globallsurgery-icn907166.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M)—office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

- 1997 documentation guidelines for evaluation and management services. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed August 17, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf

Practice Points

- Insurer scrutiny of same-day evaluation and management (E/M) and procedure services has increased, and dermatologists should be prepared for more frequent medical record reviews and audits.

- The new 2021 E/M codes actually reduce the hurdles for reporting a separate and distinct E/M service by eliminating the history and physical examination bullet points of the previous code set.

E/M Coding in 2021: The Times (and More) Are A-Changin’

Effective on January 1, 2021, the outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes underwent substantial changes, which were the culmination of multiple years of revision and surveying via the American Medical Association (AMA) Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Current Procedural Terminology (RUC-CPT) process to streamline definitions and promote consistency as well as to decrease the administrative burden for all specialties within the house of medicine.1 These updates represent a notable change from the previous documentation requirements for this oft used family of codes. Herein, we break down some of the highlights of the changes and how they may be applied for some commonly used dermatologic diagnoses.

Time Is Time Is Time

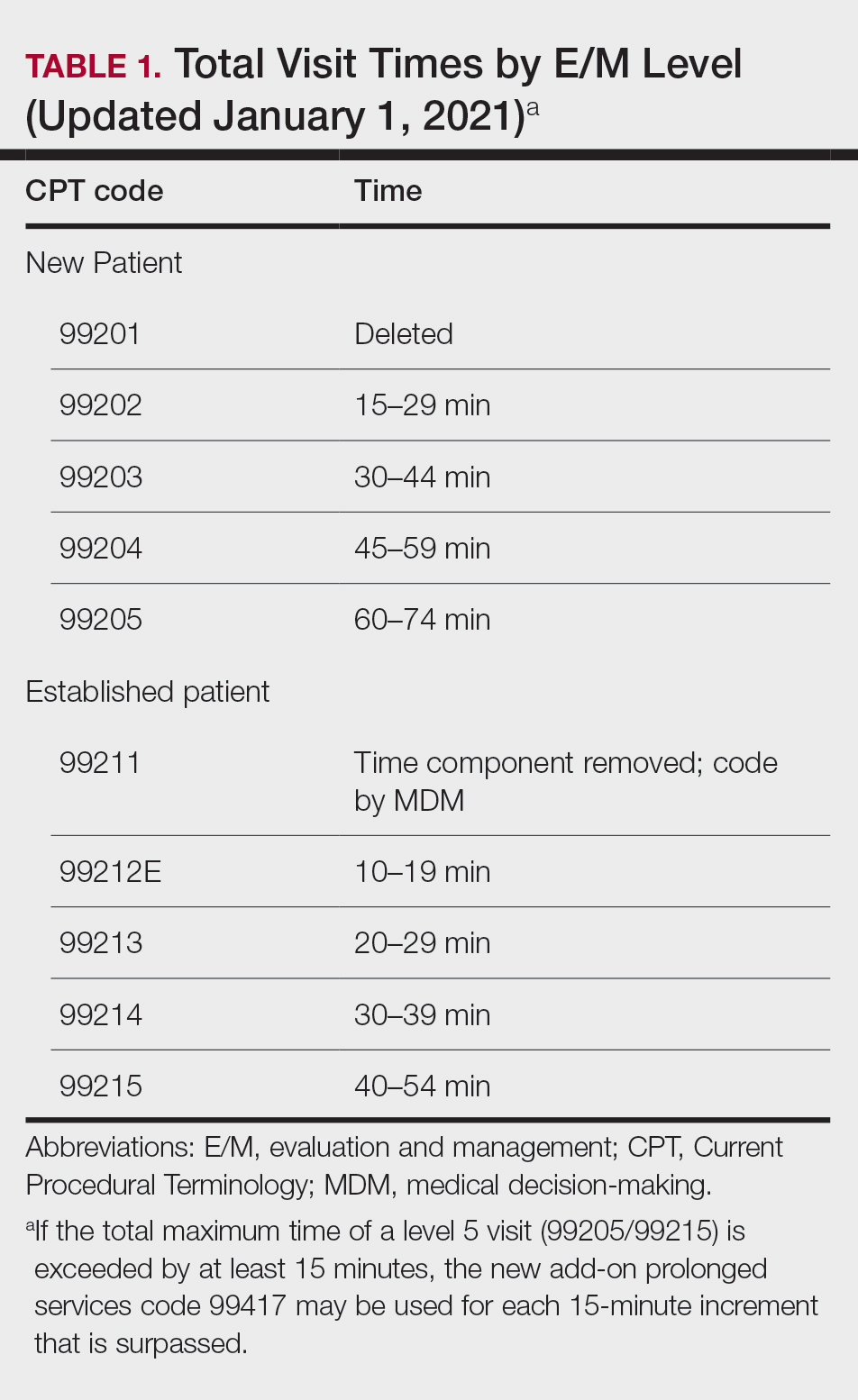

Prior to the 2021 revisions, a physician generally could only code for an E/M level by time for a face-to-face encounter dominated by counseling and/or care coordination. With the new updates, any encounter can be coded by total time spent by the physician with the patient1; however, clinical staff time is not included. There also are now clear guidelines of the time ranges corresponding to the level of E/M,1 as noted in Table 1.

Importantly, time now includes not just face-to-face time with the patient but also any time on the date of the encounter that the physician is involved in the care of the patient when not reported with a separate code. This can include reviewing notes or data before or after the examination, care coordination, ordering laboratory tests, and providing any documentation related to the encounter. Importantly, this applies only when these activities are done on the date of the encounter.

If you work with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (PA) who assists you and you are the one reporting the service, you cannot double-dip. For example, if your PA spends 10 minutes alone with a patient, you are in the room together for 5 minutes, the PA spends another 10 minutes alone with the patient afterward, and you do chart work for 10 minutes at the end of the day, the total time spent is 35 minutes, not 40 minutes, as you cannot count the time you and the PA spent together twice.

Decisions, Decisions

Evaluation and management coding also can be determined via the level of medical decision-making (MDM). Per the 2021 guidelines, MDM is comprised of 3 categories: (1) number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter, (2) amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed or analyzed, and (3) risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.1 To reach a certain overall E/M level, 2 of 3 categories must be met or exceeded. Let’s dive into each of these in a little more detail.

Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed at the Encounter

First, it is important to understand the definition of a problem addressed. Per AMA guidelines, this includes a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter that is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the physician. If the problem is referred to another provider without evaluation or consideration of treatment, it is not considered to be a problem addressed and cannot count toward this first category. An example could be a patient with a lump on the abdomen that you refer to plastic or general surgery for evaluation and treatment.

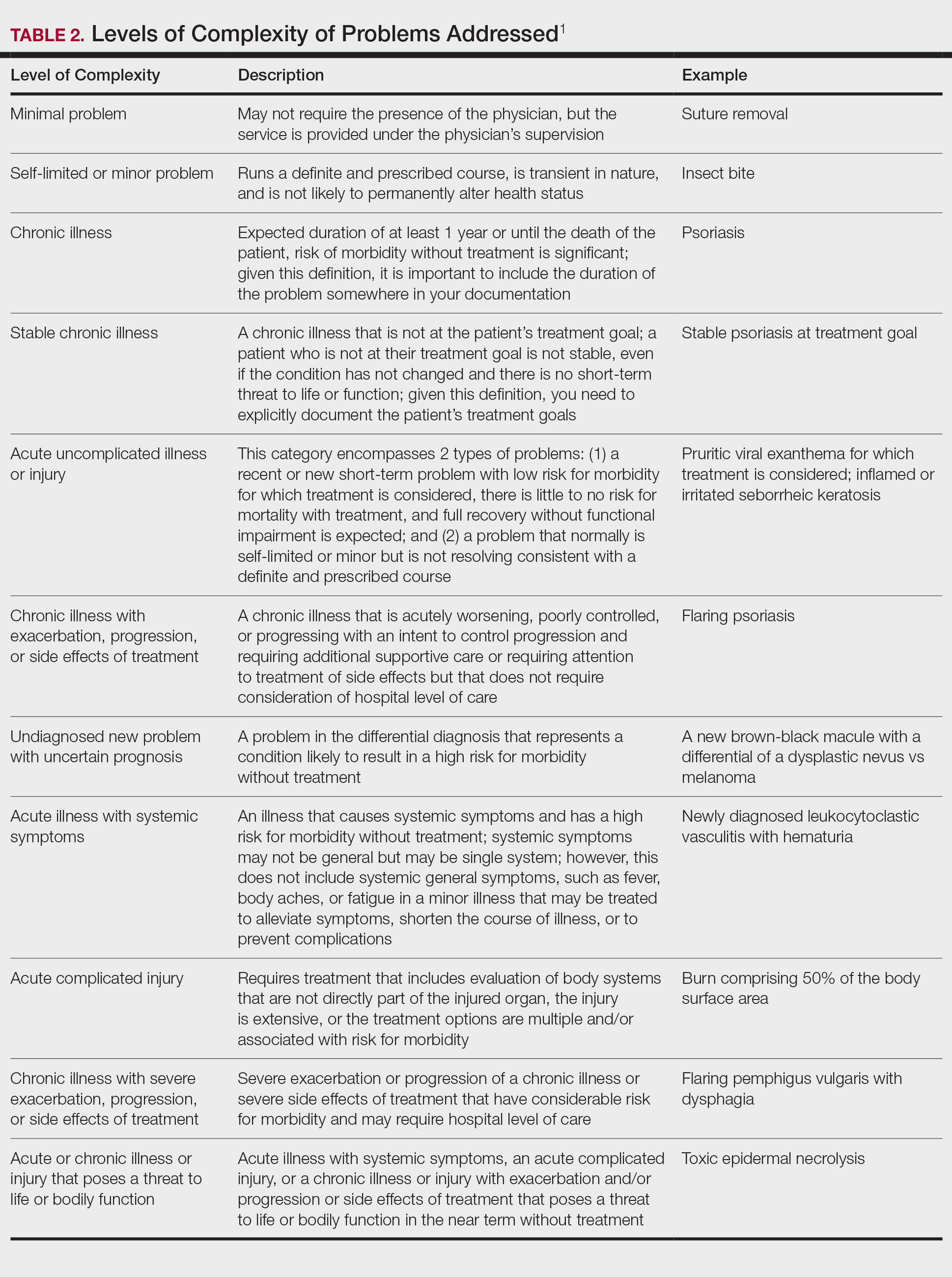

Once you have determined that you are addressing a problem, you will need to determine the level of complexity of the problem, as outlined in Table 2. Keep in mind that some entities and disease states in dermatology may fit the requirements of more than 1 level of complexity depending on the clinical situation, while there are many entities in dermatology that may not be perfectly captured by any of the levels described. In these situations, clinical judgement is required to determine where the problem would best fit. Importantly, whatever you decide, your documentation should support that decision.

Amount and/or Complexity of Data to Be Reviewed and Analyzed

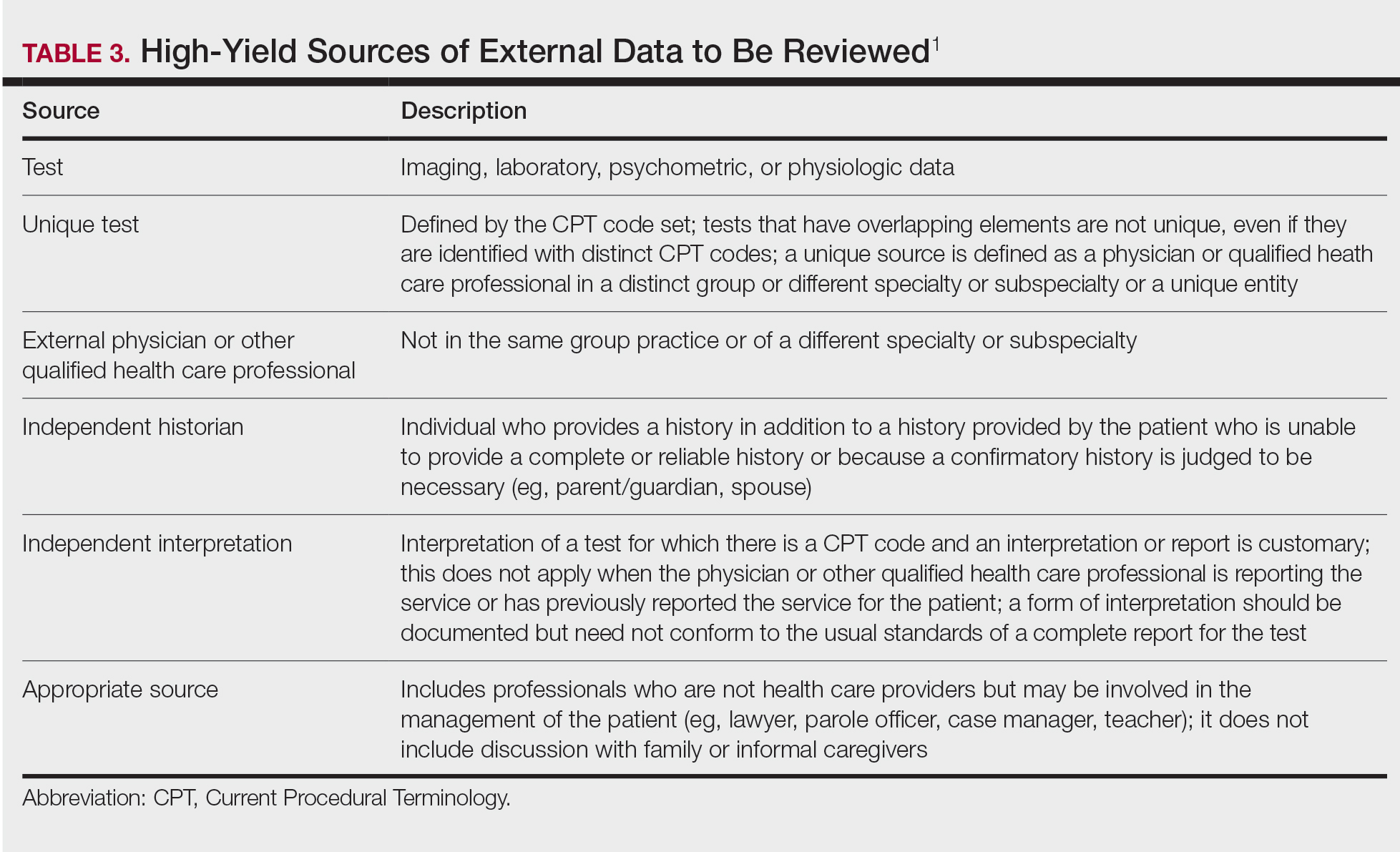

This category encompasses any external notes reviewed, unique laboratory tests or imaging ordered or reviewed, the need for an independent historian or discussion with external health care providers or appropriate sources, or independent interpretation of tests. Some high-yield definitions in this category are outlined in Table 3.

Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity or Mortality of Patient Management

In this category, risk relates to both the patient’s diagnosis and treatment(s). Importantly, for treatment and diagnostic options, these include both the options selected and those considered but not selected. Risk is defined as the probability and/or consequences of an event and is based on the usual behavior and thought processes of a physician in the same specialty. In other words, think of the risk as compared to risk in the setting of other dermatologists diagnosing and/or treating the same condition.

Social determinants of health also play a part in this category and are defined as economic and social conditions that influence the health of individuals and communities. Social determinants of health can be indicated by the specific corresponding International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code and may need to be included in your billing according to specific institutional or carrier guidelines if they are a factor in your level of MDM.

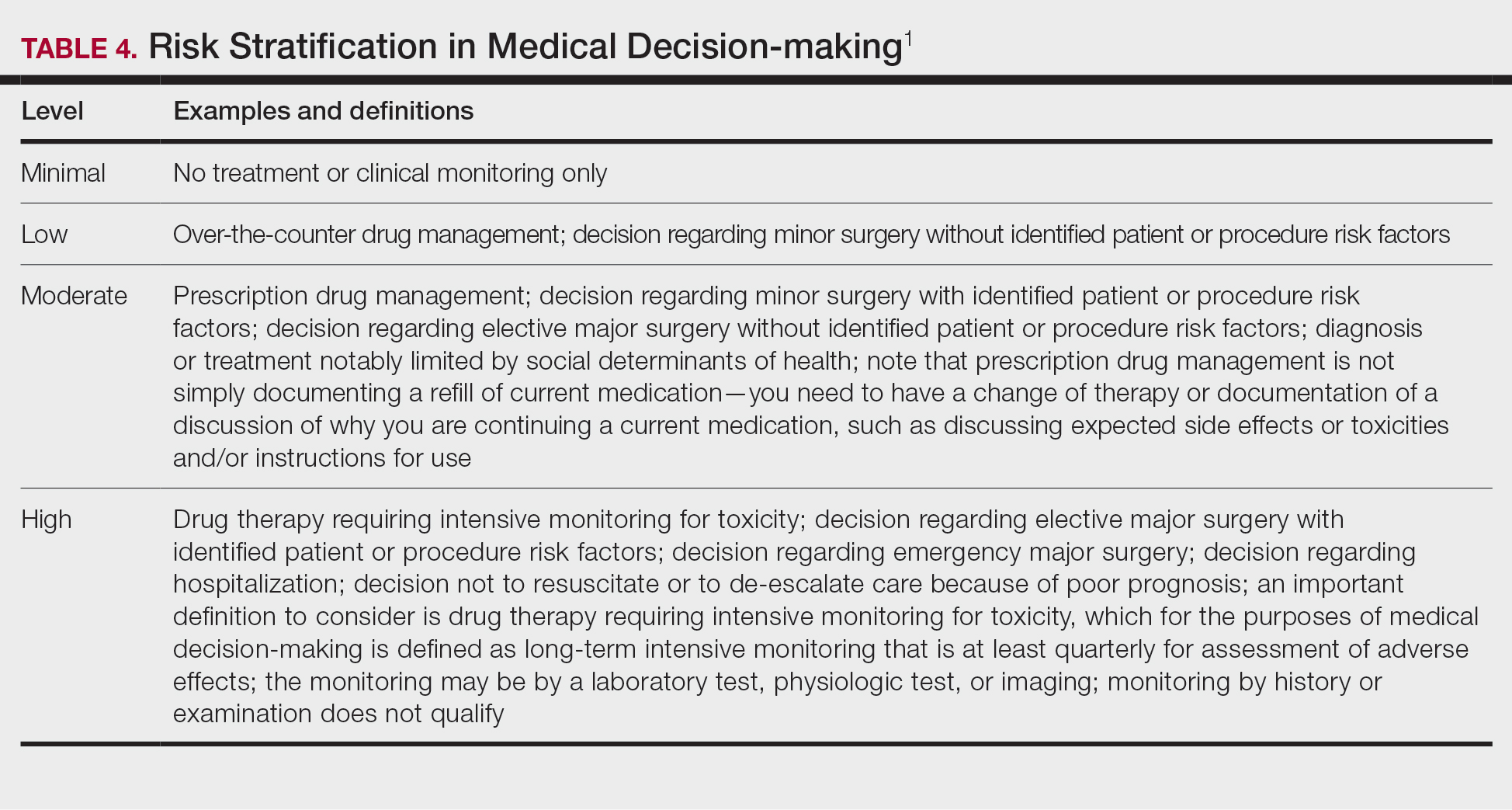

For the purposes of MDM, risk is stratified into minimal, low, moderate, and high. Some examples for each level are outlined in Table 4.

Putting It All Together

Once you have determined each of the above 3 categories, you can put them together into the MDM chart to ascertain the overall level of MDM. (The official AMA medical decision-making grid is available online [https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf]). Keep in mind that 2 of 3 columns in the table must be obtained in that level to reach an overall E/M level; for example, a visit that addresses 2 self-limited or minor problems (level 3) in which no data is reviewed (level 2) and involves prescribing a new medication (level 4), would be an overall level 3 visit.

Final Thoughts

The outpatient E/M guidelines have undergone substantial revisions; therefore, it is crucial to understand the updated definitions to ensure proper billing and documentation. History and physical examination documentation must be medically appropriate but are no longer used to determine overall E/M level; time and MDM are the sole options that can be used. Importantly, try to code as accurately as possible, documenting which problems were both noted and addressed. If you are unsure of a definition within the updated changes and MDM table, referencing the appropriate sources for guidance is recommended.

Although representing a considerable shift, the revaluation of this family of codes and the intended decrease in documentation burden has the ability to be a positive gain for dermatologists. Expect other code families to mirror these changes in the next few years.

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M) office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

Effective on January 1, 2021, the outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes underwent substantial changes, which were the culmination of multiple years of revision and surveying via the American Medical Association (AMA) Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Current Procedural Terminology (RUC-CPT) process to streamline definitions and promote consistency as well as to decrease the administrative burden for all specialties within the house of medicine.1 These updates represent a notable change from the previous documentation requirements for this oft used family of codes. Herein, we break down some of the highlights of the changes and how they may be applied for some commonly used dermatologic diagnoses.

Time Is Time Is Time

Prior to the 2021 revisions, a physician generally could only code for an E/M level by time for a face-to-face encounter dominated by counseling and/or care coordination. With the new updates, any encounter can be coded by total time spent by the physician with the patient1; however, clinical staff time is not included. There also are now clear guidelines of the time ranges corresponding to the level of E/M,1 as noted in Table 1.

Importantly, time now includes not just face-to-face time with the patient but also any time on the date of the encounter that the physician is involved in the care of the patient when not reported with a separate code. This can include reviewing notes or data before or after the examination, care coordination, ordering laboratory tests, and providing any documentation related to the encounter. Importantly, this applies only when these activities are done on the date of the encounter.

If you work with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (PA) who assists you and you are the one reporting the service, you cannot double-dip. For example, if your PA spends 10 minutes alone with a patient, you are in the room together for 5 minutes, the PA spends another 10 minutes alone with the patient afterward, and you do chart work for 10 minutes at the end of the day, the total time spent is 35 minutes, not 40 minutes, as you cannot count the time you and the PA spent together twice.

Decisions, Decisions

Evaluation and management coding also can be determined via the level of medical decision-making (MDM). Per the 2021 guidelines, MDM is comprised of 3 categories: (1) number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter, (2) amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed or analyzed, and (3) risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.1 To reach a certain overall E/M level, 2 of 3 categories must be met or exceeded. Let’s dive into each of these in a little more detail.

Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed at the Encounter

First, it is important to understand the definition of a problem addressed. Per AMA guidelines, this includes a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter that is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the physician. If the problem is referred to another provider without evaluation or consideration of treatment, it is not considered to be a problem addressed and cannot count toward this first category. An example could be a patient with a lump on the abdomen that you refer to plastic or general surgery for evaluation and treatment.

Once you have determined that you are addressing a problem, you will need to determine the level of complexity of the problem, as outlined in Table 2. Keep in mind that some entities and disease states in dermatology may fit the requirements of more than 1 level of complexity depending on the clinical situation, while there are many entities in dermatology that may not be perfectly captured by any of the levels described. In these situations, clinical judgement is required to determine where the problem would best fit. Importantly, whatever you decide, your documentation should support that decision.

Amount and/or Complexity of Data to Be Reviewed and Analyzed

This category encompasses any external notes reviewed, unique laboratory tests or imaging ordered or reviewed, the need for an independent historian or discussion with external health care providers or appropriate sources, or independent interpretation of tests. Some high-yield definitions in this category are outlined in Table 3.

Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity or Mortality of Patient Management

In this category, risk relates to both the patient’s diagnosis and treatment(s). Importantly, for treatment and diagnostic options, these include both the options selected and those considered but not selected. Risk is defined as the probability and/or consequences of an event and is based on the usual behavior and thought processes of a physician in the same specialty. In other words, think of the risk as compared to risk in the setting of other dermatologists diagnosing and/or treating the same condition.

Social determinants of health also play a part in this category and are defined as economic and social conditions that influence the health of individuals and communities. Social determinants of health can be indicated by the specific corresponding International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code and may need to be included in your billing according to specific institutional or carrier guidelines if they are a factor in your level of MDM.

For the purposes of MDM, risk is stratified into minimal, low, moderate, and high. Some examples for each level are outlined in Table 4.

Putting It All Together

Once you have determined each of the above 3 categories, you can put them together into the MDM chart to ascertain the overall level of MDM. (The official AMA medical decision-making grid is available online [https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf]). Keep in mind that 2 of 3 columns in the table must be obtained in that level to reach an overall E/M level; for example, a visit that addresses 2 self-limited or minor problems (level 3) in which no data is reviewed (level 2) and involves prescribing a new medication (level 4), would be an overall level 3 visit.

Final Thoughts

The outpatient E/M guidelines have undergone substantial revisions; therefore, it is crucial to understand the updated definitions to ensure proper billing and documentation. History and physical examination documentation must be medically appropriate but are no longer used to determine overall E/M level; time and MDM are the sole options that can be used. Importantly, try to code as accurately as possible, documenting which problems were both noted and addressed. If you are unsure of a definition within the updated changes and MDM table, referencing the appropriate sources for guidance is recommended.

Although representing a considerable shift, the revaluation of this family of codes and the intended decrease in documentation burden has the ability to be a positive gain for dermatologists. Expect other code families to mirror these changes in the next few years.

Effective on January 1, 2021, the outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes underwent substantial changes, which were the culmination of multiple years of revision and surveying via the American Medical Association (AMA) Relative Value Scale Update Committee and Current Procedural Terminology (RUC-CPT) process to streamline definitions and promote consistency as well as to decrease the administrative burden for all specialties within the house of medicine.1 These updates represent a notable change from the previous documentation requirements for this oft used family of codes. Herein, we break down some of the highlights of the changes and how they may be applied for some commonly used dermatologic diagnoses.

Time Is Time Is Time

Prior to the 2021 revisions, a physician generally could only code for an E/M level by time for a face-to-face encounter dominated by counseling and/or care coordination. With the new updates, any encounter can be coded by total time spent by the physician with the patient1; however, clinical staff time is not included. There also are now clear guidelines of the time ranges corresponding to the level of E/M,1 as noted in Table 1.

Importantly, time now includes not just face-to-face time with the patient but also any time on the date of the encounter that the physician is involved in the care of the patient when not reported with a separate code. This can include reviewing notes or data before or after the examination, care coordination, ordering laboratory tests, and providing any documentation related to the encounter. Importantly, this applies only when these activities are done on the date of the encounter.

If you work with a nurse practitioner or physician assistant (PA) who assists you and you are the one reporting the service, you cannot double-dip. For example, if your PA spends 10 minutes alone with a patient, you are in the room together for 5 minutes, the PA spends another 10 minutes alone with the patient afterward, and you do chart work for 10 minutes at the end of the day, the total time spent is 35 minutes, not 40 minutes, as you cannot count the time you and the PA spent together twice.

Decisions, Decisions

Evaluation and management coding also can be determined via the level of medical decision-making (MDM). Per the 2021 guidelines, MDM is comprised of 3 categories: (1) number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter, (2) amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed or analyzed, and (3) risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.1 To reach a certain overall E/M level, 2 of 3 categories must be met or exceeded. Let’s dive into each of these in a little more detail.

Number and Complexity of Problems Addressed at the Encounter

First, it is important to understand the definition of a problem addressed. Per AMA guidelines, this includes a disease, condition, illness, injury, symptom, sign, finding, complaint, or other matter addressed at the encounter that is evaluated or treated at the encounter by the physician. If the problem is referred to another provider without evaluation or consideration of treatment, it is not considered to be a problem addressed and cannot count toward this first category. An example could be a patient with a lump on the abdomen that you refer to plastic or general surgery for evaluation and treatment.

Once you have determined that you are addressing a problem, you will need to determine the level of complexity of the problem, as outlined in Table 2. Keep in mind that some entities and disease states in dermatology may fit the requirements of more than 1 level of complexity depending on the clinical situation, while there are many entities in dermatology that may not be perfectly captured by any of the levels described. In these situations, clinical judgement is required to determine where the problem would best fit. Importantly, whatever you decide, your documentation should support that decision.

Amount and/or Complexity of Data to Be Reviewed and Analyzed

This category encompasses any external notes reviewed, unique laboratory tests or imaging ordered or reviewed, the need for an independent historian or discussion with external health care providers or appropriate sources, or independent interpretation of tests. Some high-yield definitions in this category are outlined in Table 3.

Risk of Complications and/or Morbidity or Mortality of Patient Management

In this category, risk relates to both the patient’s diagnosis and treatment(s). Importantly, for treatment and diagnostic options, these include both the options selected and those considered but not selected. Risk is defined as the probability and/or consequences of an event and is based on the usual behavior and thought processes of a physician in the same specialty. In other words, think of the risk as compared to risk in the setting of other dermatologists diagnosing and/or treating the same condition.

Social determinants of health also play a part in this category and are defined as economic and social conditions that influence the health of individuals and communities. Social determinants of health can be indicated by the specific corresponding International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code and may need to be included in your billing according to specific institutional or carrier guidelines if they are a factor in your level of MDM.

For the purposes of MDM, risk is stratified into minimal, low, moderate, and high. Some examples for each level are outlined in Table 4.

Putting It All Together

Once you have determined each of the above 3 categories, you can put them together into the MDM chart to ascertain the overall level of MDM. (The official AMA medical decision-making grid is available online [https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-revised-mdm-grid.pdf]). Keep in mind that 2 of 3 columns in the table must be obtained in that level to reach an overall E/M level; for example, a visit that addresses 2 self-limited or minor problems (level 3) in which no data is reviewed (level 2) and involves prescribing a new medication (level 4), would be an overall level 3 visit.

Final Thoughts

The outpatient E/M guidelines have undergone substantial revisions; therefore, it is crucial to understand the updated definitions to ensure proper billing and documentation. History and physical examination documentation must be medically appropriate but are no longer used to determine overall E/M level; time and MDM are the sole options that can be used. Importantly, try to code as accurately as possible, documenting which problems were both noted and addressed. If you are unsure of a definition within the updated changes and MDM table, referencing the appropriate sources for guidance is recommended.

Although representing a considerable shift, the revaluation of this family of codes and the intended decrease in documentation burden has the ability to be a positive gain for dermatologists. Expect other code families to mirror these changes in the next few years.

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M) office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT® Evaluation and management (E/M) office or other outpatient (99202-99215) and prolonged services (99354, 99355, 99356, 99417) code and guideline changes. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-06/cpt-office-prolonged-svs-code-changes.pdf

Practice Points

- The outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) codes have undergone substantial changes that took effect January 1, 2021.

- Outpatient E/M visits are now coded based on time or level of medical decision-making (MDM).

- Time now includes all preservice, intraservice, and postservice time the physician spends with the patient on the date of the encounter.

- Many of the key definitions used in order to determine level of MDM have been streamlined and updated.

Practice Expense–Only Codes: No Physician Work, No Sweat

I have written previously about Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedure codes submitted on the same date of service as evaluation and management (E/M) services in the context of modifier -25.1 Billing same-day procedures and E/M services is under close scrutiny by insurers, and accurate and complete documentation is a must.2 An understanding of what aspects of evaluation are included in the global surgical package is critical in deciding whether a separate and distinct same-day evaluation was performed. In general, the decision to perform a procedure is included in the payment for the procedure itself, as is the examination of the body site in question, diagnosis of the medical condition, discussion of treatment options, and postoperative services related to the procedure. This is true for CPT codes that contain physician work, which constitute the majority of CPT codes reported by dermatologists.3

However, there is one set of codes where these principles do not apply: the practice expense (PE)–only codes, or no physician work codes. These codes are defined by CPT and the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) of the American Medical Association as containing no physician work. Their valuations are based only on staff/nursing time and the other aspects of direct and indirect practice costs included in providing the service, such as gauze, sutures, equipment, office rent, and utilities.4 Examples of PE-only codes include the nonphysician-performed photodynamic therapy code 96567; phototherapy codes 96900, 96910, and 96912; and patch testing and photopatch testing codes 95044, 95052, and 95056.

For PE-only codes, only the provision of the service by staff is included in the code reimbursement; there is no physician time or work built into these codes. Thus, neither the initial evaluation of the patient by the physician, the decision to perform the procedure, nor the evaluation of therapy effectiveness or side effects or interpretation of the results is included. Understanding that there is no physician involvement in PE-only codes is critical in deciding whether an E/M service should be billed on the same day as a PE-only code. To that end, although a physician does not actually have to personally evaluate the patient on the day of service to bill PE-only codes, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has indicated that a physician or qualified medical provider must be on premises.5 Billing for PE-only services when no provider is present will be interpreted as a false claim or fraudulent billing practice.

Because PE-only codes do not include physician work, an E/M service will be billed in addition to the treatment almost any time a same-day physician evaluation is performed. For example, if a patient presents with a changing mole that is evaluated on the same date of service as phototherapy for the treatment of psoriasis, that service is clearly reportable with an E/M code because the mole check is separate and distinct from the phototherapy treatment. A more common scenario is for the physician to see a patient with a rash consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis and the decision to perform same-day patch testing is made. In this circumstance, the E/M service is still reportable because the evaluation of the rash and the decision to perform patch testing are not included in this PE-only code.

Phototherapy typically is provided as a prolonged course of multiple treatments, and reporting of same-day E/M services during the course of therapy is common. Phototherapy must be monitored by the physician for clinical effectiveness, dose changes, and side effects, as well as to determine whether to continue therapy. A standard operating procedure should be created to document that the physician typically evaluates the patient’s progress at set intervals or as dictated by patient or staff concerns. Reporting an E/M service with every phototherapy session is not considered medically necessary. Moreover, a nurse evaluation of the patient prior to each phototherapy treatment, including questions on disease severity, how the patient did with the last treatment, and whether medications have changed, is included in the payment for the phototherapy codes. Only formal and medically necessary physician E/M services should be billed, not drive-by visits in which the physician pops in just to see how the patient is doing.

Final Thoughts

Practice expense–only codes include no payment for physician time or work but require the presence of a qualified health care provider on premises to bill. Medically necessary physician evaluations on the same day as PE-only services will typically result in both an E/M service and the procedure being reported. Understanding performance and documentation requirements of PE-only codes is critical for proper reimbursement for a dermatology practice.

- Rogers H. One diagnosis and modifier -25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Rogers H. Modifier -25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Medicare update. Derm Coding Consult. March 2001;5:5-7. https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Global%20navigation/Member%20tools%20and%20benefits/Publications/Derm%20Coding%20Consult%20archives/2001-spring.pdf.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2018, Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2018.

- Determining who has the authority to bill. The Dermatologist. September 4, 2018. https://www.the-dermatologist.com/article/3006. Accessed October 25, 2018.

I have written previously about Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedure codes submitted on the same date of service as evaluation and management (E/M) services in the context of modifier -25.1 Billing same-day procedures and E/M services is under close scrutiny by insurers, and accurate and complete documentation is a must.2 An understanding of what aspects of evaluation are included in the global surgical package is critical in deciding whether a separate and distinct same-day evaluation was performed. In general, the decision to perform a procedure is included in the payment for the procedure itself, as is the examination of the body site in question, diagnosis of the medical condition, discussion of treatment options, and postoperative services related to the procedure. This is true for CPT codes that contain physician work, which constitute the majority of CPT codes reported by dermatologists.3

However, there is one set of codes where these principles do not apply: the practice expense (PE)–only codes, or no physician work codes. These codes are defined by CPT and the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) of the American Medical Association as containing no physician work. Their valuations are based only on staff/nursing time and the other aspects of direct and indirect practice costs included in providing the service, such as gauze, sutures, equipment, office rent, and utilities.4 Examples of PE-only codes include the nonphysician-performed photodynamic therapy code 96567; phototherapy codes 96900, 96910, and 96912; and patch testing and photopatch testing codes 95044, 95052, and 95056.

For PE-only codes, only the provision of the service by staff is included in the code reimbursement; there is no physician time or work built into these codes. Thus, neither the initial evaluation of the patient by the physician, the decision to perform the procedure, nor the evaluation of therapy effectiveness or side effects or interpretation of the results is included. Understanding that there is no physician involvement in PE-only codes is critical in deciding whether an E/M service should be billed on the same day as a PE-only code. To that end, although a physician does not actually have to personally evaluate the patient on the day of service to bill PE-only codes, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has indicated that a physician or qualified medical provider must be on premises.5 Billing for PE-only services when no provider is present will be interpreted as a false claim or fraudulent billing practice.

Because PE-only codes do not include physician work, an E/M service will be billed in addition to the treatment almost any time a same-day physician evaluation is performed. For example, if a patient presents with a changing mole that is evaluated on the same date of service as phototherapy for the treatment of psoriasis, that service is clearly reportable with an E/M code because the mole check is separate and distinct from the phototherapy treatment. A more common scenario is for the physician to see a patient with a rash consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis and the decision to perform same-day patch testing is made. In this circumstance, the E/M service is still reportable because the evaluation of the rash and the decision to perform patch testing are not included in this PE-only code.

Phototherapy typically is provided as a prolonged course of multiple treatments, and reporting of same-day E/M services during the course of therapy is common. Phototherapy must be monitored by the physician for clinical effectiveness, dose changes, and side effects, as well as to determine whether to continue therapy. A standard operating procedure should be created to document that the physician typically evaluates the patient’s progress at set intervals or as dictated by patient or staff concerns. Reporting an E/M service with every phototherapy session is not considered medically necessary. Moreover, a nurse evaluation of the patient prior to each phototherapy treatment, including questions on disease severity, how the patient did with the last treatment, and whether medications have changed, is included in the payment for the phototherapy codes. Only formal and medically necessary physician E/M services should be billed, not drive-by visits in which the physician pops in just to see how the patient is doing.

Final Thoughts

Practice expense–only codes include no payment for physician time or work but require the presence of a qualified health care provider on premises to bill. Medically necessary physician evaluations on the same day as PE-only services will typically result in both an E/M service and the procedure being reported. Understanding performance and documentation requirements of PE-only codes is critical for proper reimbursement for a dermatology practice.

I have written previously about Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedure codes submitted on the same date of service as evaluation and management (E/M) services in the context of modifier -25.1 Billing same-day procedures and E/M services is under close scrutiny by insurers, and accurate and complete documentation is a must.2 An understanding of what aspects of evaluation are included in the global surgical package is critical in deciding whether a separate and distinct same-day evaluation was performed. In general, the decision to perform a procedure is included in the payment for the procedure itself, as is the examination of the body site in question, diagnosis of the medical condition, discussion of treatment options, and postoperative services related to the procedure. This is true for CPT codes that contain physician work, which constitute the majority of CPT codes reported by dermatologists.3

However, there is one set of codes where these principles do not apply: the practice expense (PE)–only codes, or no physician work codes. These codes are defined by CPT and the Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) of the American Medical Association as containing no physician work. Their valuations are based only on staff/nursing time and the other aspects of direct and indirect practice costs included in providing the service, such as gauze, sutures, equipment, office rent, and utilities.4 Examples of PE-only codes include the nonphysician-performed photodynamic therapy code 96567; phototherapy codes 96900, 96910, and 96912; and patch testing and photopatch testing codes 95044, 95052, and 95056.

For PE-only codes, only the provision of the service by staff is included in the code reimbursement; there is no physician time or work built into these codes. Thus, neither the initial evaluation of the patient by the physician, the decision to perform the procedure, nor the evaluation of therapy effectiveness or side effects or interpretation of the results is included. Understanding that there is no physician involvement in PE-only codes is critical in deciding whether an E/M service should be billed on the same day as a PE-only code. To that end, although a physician does not actually have to personally evaluate the patient on the day of service to bill PE-only codes, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has indicated that a physician or qualified medical provider must be on premises.5 Billing for PE-only services when no provider is present will be interpreted as a false claim or fraudulent billing practice.

Because PE-only codes do not include physician work, an E/M service will be billed in addition to the treatment almost any time a same-day physician evaluation is performed. For example, if a patient presents with a changing mole that is evaluated on the same date of service as phototherapy for the treatment of psoriasis, that service is clearly reportable with an E/M code because the mole check is separate and distinct from the phototherapy treatment. A more common scenario is for the physician to see a patient with a rash consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis and the decision to perform same-day patch testing is made. In this circumstance, the E/M service is still reportable because the evaluation of the rash and the decision to perform patch testing are not included in this PE-only code.

Phototherapy typically is provided as a prolonged course of multiple treatments, and reporting of same-day E/M services during the course of therapy is common. Phototherapy must be monitored by the physician for clinical effectiveness, dose changes, and side effects, as well as to determine whether to continue therapy. A standard operating procedure should be created to document that the physician typically evaluates the patient’s progress at set intervals or as dictated by patient or staff concerns. Reporting an E/M service with every phototherapy session is not considered medically necessary. Moreover, a nurse evaluation of the patient prior to each phototherapy treatment, including questions on disease severity, how the patient did with the last treatment, and whether medications have changed, is included in the payment for the phototherapy codes. Only formal and medically necessary physician E/M services should be billed, not drive-by visits in which the physician pops in just to see how the patient is doing.

Final Thoughts

Practice expense–only codes include no payment for physician time or work but require the presence of a qualified health care provider on premises to bill. Medically necessary physician evaluations on the same day as PE-only services will typically result in both an E/M service and the procedure being reported. Understanding performance and documentation requirements of PE-only codes is critical for proper reimbursement for a dermatology practice.

- Rogers H. One diagnosis and modifier -25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Rogers H. Modifier -25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Medicare update. Derm Coding Consult. March 2001;5:5-7. https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Global%20navigation/Member%20tools%20and%20benefits/Publications/Derm%20Coding%20Consult%20archives/2001-spring.pdf.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2018, Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2018.

- Determining who has the authority to bill. The Dermatologist. September 4, 2018. https://www.the-dermatologist.com/article/3006. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- Rogers H. One diagnosis and modifier -25: appropriate or audit target? Cutis. 2017;99:165-166.

- Rogers H. Modifier -25 victory, but the battle is not over. Cutis. 2018;101:409-410.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Medicare update. Derm Coding Consult. March 2001;5:5-7. https://www.aad.org/File%20Library/Global%20navigation/Member%20tools%20and%20benefits/Publications/Derm%20Coding%20Consult%20archives/2001-spring.pdf.

- Current Procedural Terminology 2018, Professional Edition. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2018.

- Determining who has the authority to bill. The Dermatologist. September 4, 2018. https://www.the-dermatologist.com/article/3006. Accessed October 25, 2018.

Practice Points

- Billing same-day procedures and evaluation and management services is under close scrutiny by insurers, and accurate and complete documentation is a must.

- For practice expense–only codes, only the provision of the service by staff is included in the code reimbursement; there is no physician time or work built into these codes.

- Practice expense–only codes require the presence of a qualified health care provider on premises to bill.

Modifier -25 Victory, But the Battle Is Not Over

On February 23, 2018, Anthem Insurance Companies, Inc, announced the reversal of its proposed policy to reduce reimbursement for evaluation and management (E/M) services billed using modifier -25.1 This win for physicians was the result of a broad-based, multipronged advocacy campaign, and the American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) was critical to this victory.

Dermatology Took the Lead in Opposing Policy That Would Reduce Reimbursement

Dermatology was the first to trumpet the dangers of modifier -25 reduction policies and explain why other specialty societies should care. The AADA took the lead in assembling a coalition of physician groups to oppose the proposed policy by sharing language for opposition letters and meeting talking points with many societies outside of dermatology as well as producing the first draft for the American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates’ resolution that spurred action against Anthem’s proposed policy.2 Members of the AADA attended numerous conference calls and in-person meetings with health insurance officials to urge them to reverse the policy and helped coordinate opposition from state and national specialty societies. The influence and advocacy of the AMA was critical in reversing the proposed policy, but dermatology started the opposition and organized the players to bring the fight against Anthem.

AADA Continues to Fight

Despite the victory against Anthem, challenges to fair reimbursement of modifier -25 claims are ongoing. Two insurers recently announced implementation of new modifier -25 reduction policies.3,4 Moreover, 4 other insurers have existing modifier -25 reduction policies in place.5-8 The AADA has engaged, and will continue engaging, each of these insurers with the message that the ability to perform procedures and distinct E/M services on the same day is integral to efficient, patient-centered care of dermatologic diseases. The AADA argues that insurers’ rationale (overlapping indirect practice expenses) for payment reduction is improper and that appropriately documented modifier -25 claims should be reimbursed at 100% of allowable charges.