User login

Biomarker use in ARDS resulting from COVID-19 infection

There is renewed interest in the use of immunomodulator therapies in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Beyond COVID-19, studies have also shown corticosteroid therapy improves clinical outcomes in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia.3 However, the overwhelming majority of studies identifying plasma biomarkers that are associated with clinical outcomes in severe lung injury predate the routine use of corticosteroids.4 Two investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital, Jehan W. Alladina, MD, and George A. Alba, MD, performed a study to assess whether plasma biomarkers previously associated with clinical outcomes in ARDS maintained their predictive value in the setting of widespread immunomodulator therapy in the ICU. Drs. Alladina and Alba are physician-scientists and codirectors of the Program for Advancing Critical Care Translational Science at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

In a study published in CHEST®Critical Care earlier this year, they prospectively enrolled patients with ARDS due to confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic from December 31, 2020, to March 31, 2021, at Massachusetts General Hospital.5 Plasma samples were collected within 24 hours of intubation for mechanical ventilation for protein analysis in 69 patients. Baseline demographics included a mean age of 62 plus or minus 15 years and a BMI of 31 plus or minus 8, and 45% were female. The median PaO2 to FiO2 ratio was 174 mm Hg, consistent with moderate ARDS, and the median duration of ventilation was 17 days. The patients had a median modified sequential organ failure assessment score of 8.5, and in-hospital mortality was 44% by 60 days. Notably, all patients in this cohort received steroids during their ICU stay.

Interestingly, the study investigators found no association between clinical outcomes and circulating proteins implicated in inflammation (eg, interleukin [IL]-6, IL-8), epithelial injury (eg, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, surfactant protein D), or coagulation (eg, D-dimer, tissue factor). However, four endothelial biomarkers—von Willebrand factor A2 domain; angiopoietin-2; syndecan-1; and neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 9 (NEDD9)—were associated with 60-day mortality after adjusting for age, sex, and severity of illness. A sensitivity analysis, in which patients treated with the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (n=4) were excluded, showed similar results.

Of the endothelial proteins, NEDD9 demonstrated the greatest effect size in its association with mortality in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 who were treated with immunomodulators. NEDD9 is a scaffolding protein highly expressed in the pulmonary vascular endothelium, but its role in ARDS is not well known. In pulmonary vascular disease, plasma levels are associated with adverse pulmonary hemodynamics and clinical outcomes. Pulmonary artery endothelial NEDD9 is upregulated by cellular hypoxia and can mediate platelet-endothelial adhesion by interacting with P-selectin on the surface of activated platelets.6 Additionally, there is evidence of increased pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 expression and colocalization with fibrin within pulmonary arteries in lung tissue of patients who died from ARDS due to COVID-19.7 Thus, NEDD9 may be an important mediator of pulmonary vascular dysfunction observed in ARDS and could be a novel biomarker for patient subphenotyping and prognostication of clinical outcomes.

In summary, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 ARDS uniformly treated with corticosteroids, plasma biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation, and epithelial injury were not associated with clinical outcomes, but endothelial biomarkers remained prognostic. It is biologically plausible that immunomodulators could attenuate the association between inflammatory biomarkers and patient outcomes. The findings of this study highlight the association of endothelial biomarkers with clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 ARDS treated with immunomodulators and warrant prospective validation, especially with the increasing evidence-based use of antiinflammatory therapy in acute lung injury. However, there are several important limitations to consider, including a small sample size from a single institution that precludes any definitive conclusions regarding any negative associations. Moreover, the single time point studied (the day of initiation of mechanical ventilation) and absence of a comparator group do not allow a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of antiinflammatory therapies across the trajectory of disease. Whether the findings are generalizable to all patients with ARDS treated with immunomodulators also remains unknown.

Overall, these data suggest that circulating signatures previously associated with ARDS, particularly those related to systemic inflammation, may have limited prognostic utility in the era of increasing immunomodulator use in critical illness. A deeper understanding of the pathobiology of ARDS, including the complex interplay with systemic immunomodulation, is needed to identify prognostic biomarkers and targeted therapies that improve patient outcomes.

Both authors work in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, in Boston.

References

1. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al; RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704.

2. Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, et al. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1-11.

3. Dequin P-F, Meziani F, Quenot J-P, et al. Hydrocortisone in severe community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1931-1941.

4. Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang H-H, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1636-1643.

5. Alladina JW, Giacona FL, Haring AM, et al. Circulating biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction associated with ventilatory ratio and mortality in ARDS resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection treated with antiinflammatory therapies. CHEST Crit Care. 2024;2(2):100054.

6. Alba GA, Samokhin AO, Wang R-S, et al. NEDD9 is a novel and modifiable mediator of platelet-endothelial adhesion in the pulmonary circulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(12):1533-1545.

7. Alba GA, Samokhin AO, Wang R-S, et al. Pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 and the prothrombotic pathophenotype of acute respiratory distress syndrome due to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(2):e12071.

There is renewed interest in the use of immunomodulator therapies in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Beyond COVID-19, studies have also shown corticosteroid therapy improves clinical outcomes in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia.3 However, the overwhelming majority of studies identifying plasma biomarkers that are associated with clinical outcomes in severe lung injury predate the routine use of corticosteroids.4 Two investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital, Jehan W. Alladina, MD, and George A. Alba, MD, performed a study to assess whether plasma biomarkers previously associated with clinical outcomes in ARDS maintained their predictive value in the setting of widespread immunomodulator therapy in the ICU. Drs. Alladina and Alba are physician-scientists and codirectors of the Program for Advancing Critical Care Translational Science at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

In a study published in CHEST®Critical Care earlier this year, they prospectively enrolled patients with ARDS due to confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic from December 31, 2020, to March 31, 2021, at Massachusetts General Hospital.5 Plasma samples were collected within 24 hours of intubation for mechanical ventilation for protein analysis in 69 patients. Baseline demographics included a mean age of 62 plus or minus 15 years and a BMI of 31 plus or minus 8, and 45% were female. The median PaO2 to FiO2 ratio was 174 mm Hg, consistent with moderate ARDS, and the median duration of ventilation was 17 days. The patients had a median modified sequential organ failure assessment score of 8.5, and in-hospital mortality was 44% by 60 days. Notably, all patients in this cohort received steroids during their ICU stay.

Interestingly, the study investigators found no association between clinical outcomes and circulating proteins implicated in inflammation (eg, interleukin [IL]-6, IL-8), epithelial injury (eg, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, surfactant protein D), or coagulation (eg, D-dimer, tissue factor). However, four endothelial biomarkers—von Willebrand factor A2 domain; angiopoietin-2; syndecan-1; and neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 9 (NEDD9)—were associated with 60-day mortality after adjusting for age, sex, and severity of illness. A sensitivity analysis, in which patients treated with the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (n=4) were excluded, showed similar results.

Of the endothelial proteins, NEDD9 demonstrated the greatest effect size in its association with mortality in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 who were treated with immunomodulators. NEDD9 is a scaffolding protein highly expressed in the pulmonary vascular endothelium, but its role in ARDS is not well known. In pulmonary vascular disease, plasma levels are associated with adverse pulmonary hemodynamics and clinical outcomes. Pulmonary artery endothelial NEDD9 is upregulated by cellular hypoxia and can mediate platelet-endothelial adhesion by interacting with P-selectin on the surface of activated platelets.6 Additionally, there is evidence of increased pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 expression and colocalization with fibrin within pulmonary arteries in lung tissue of patients who died from ARDS due to COVID-19.7 Thus, NEDD9 may be an important mediator of pulmonary vascular dysfunction observed in ARDS and could be a novel biomarker for patient subphenotyping and prognostication of clinical outcomes.

In summary, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 ARDS uniformly treated with corticosteroids, plasma biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation, and epithelial injury were not associated with clinical outcomes, but endothelial biomarkers remained prognostic. It is biologically plausible that immunomodulators could attenuate the association between inflammatory biomarkers and patient outcomes. The findings of this study highlight the association of endothelial biomarkers with clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 ARDS treated with immunomodulators and warrant prospective validation, especially with the increasing evidence-based use of antiinflammatory therapy in acute lung injury. However, there are several important limitations to consider, including a small sample size from a single institution that precludes any definitive conclusions regarding any negative associations. Moreover, the single time point studied (the day of initiation of mechanical ventilation) and absence of a comparator group do not allow a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of antiinflammatory therapies across the trajectory of disease. Whether the findings are generalizable to all patients with ARDS treated with immunomodulators also remains unknown.

Overall, these data suggest that circulating signatures previously associated with ARDS, particularly those related to systemic inflammation, may have limited prognostic utility in the era of increasing immunomodulator use in critical illness. A deeper understanding of the pathobiology of ARDS, including the complex interplay with systemic immunomodulation, is needed to identify prognostic biomarkers and targeted therapies that improve patient outcomes.

Both authors work in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, in Boston.

References

1. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al; RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704.

2. Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, et al. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1-11.

3. Dequin P-F, Meziani F, Quenot J-P, et al. Hydrocortisone in severe community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1931-1941.

4. Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang H-H, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1636-1643.

5. Alladina JW, Giacona FL, Haring AM, et al. Circulating biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction associated with ventilatory ratio and mortality in ARDS resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection treated with antiinflammatory therapies. CHEST Crit Care. 2024;2(2):100054.

6. Alba GA, Samokhin AO, Wang R-S, et al. NEDD9 is a novel and modifiable mediator of platelet-endothelial adhesion in the pulmonary circulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(12):1533-1545.

7. Alba GA, Samokhin AO, Wang R-S, et al. Pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 and the prothrombotic pathophenotype of acute respiratory distress syndrome due to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(2):e12071.

There is renewed interest in the use of immunomodulator therapies in patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

Beyond COVID-19, studies have also shown corticosteroid therapy improves clinical outcomes in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia.3 However, the overwhelming majority of studies identifying plasma biomarkers that are associated with clinical outcomes in severe lung injury predate the routine use of corticosteroids.4 Two investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital, Jehan W. Alladina, MD, and George A. Alba, MD, performed a study to assess whether plasma biomarkers previously associated with clinical outcomes in ARDS maintained their predictive value in the setting of widespread immunomodulator therapy in the ICU. Drs. Alladina and Alba are physician-scientists and codirectors of the Program for Advancing Critical Care Translational Science at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

In a study published in CHEST®Critical Care earlier this year, they prospectively enrolled patients with ARDS due to confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic from December 31, 2020, to March 31, 2021, at Massachusetts General Hospital.5 Plasma samples were collected within 24 hours of intubation for mechanical ventilation for protein analysis in 69 patients. Baseline demographics included a mean age of 62 plus or minus 15 years and a BMI of 31 plus or minus 8, and 45% were female. The median PaO2 to FiO2 ratio was 174 mm Hg, consistent with moderate ARDS, and the median duration of ventilation was 17 days. The patients had a median modified sequential organ failure assessment score of 8.5, and in-hospital mortality was 44% by 60 days. Notably, all patients in this cohort received steroids during their ICU stay.

Interestingly, the study investigators found no association between clinical outcomes and circulating proteins implicated in inflammation (eg, interleukin [IL]-6, IL-8), epithelial injury (eg, soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products, surfactant protein D), or coagulation (eg, D-dimer, tissue factor). However, four endothelial biomarkers—von Willebrand factor A2 domain; angiopoietin-2; syndecan-1; and neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 9 (NEDD9)—were associated with 60-day mortality after adjusting for age, sex, and severity of illness. A sensitivity analysis, in which patients treated with the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (n=4) were excluded, showed similar results.

Of the endothelial proteins, NEDD9 demonstrated the greatest effect size in its association with mortality in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 who were treated with immunomodulators. NEDD9 is a scaffolding protein highly expressed in the pulmonary vascular endothelium, but its role in ARDS is not well known. In pulmonary vascular disease, plasma levels are associated with adverse pulmonary hemodynamics and clinical outcomes. Pulmonary artery endothelial NEDD9 is upregulated by cellular hypoxia and can mediate platelet-endothelial adhesion by interacting with P-selectin on the surface of activated platelets.6 Additionally, there is evidence of increased pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 expression and colocalization with fibrin within pulmonary arteries in lung tissue of patients who died from ARDS due to COVID-19.7 Thus, NEDD9 may be an important mediator of pulmonary vascular dysfunction observed in ARDS and could be a novel biomarker for patient subphenotyping and prognostication of clinical outcomes.

In summary, in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 ARDS uniformly treated with corticosteroids, plasma biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation, and epithelial injury were not associated with clinical outcomes, but endothelial biomarkers remained prognostic. It is biologically plausible that immunomodulators could attenuate the association between inflammatory biomarkers and patient outcomes. The findings of this study highlight the association of endothelial biomarkers with clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 ARDS treated with immunomodulators and warrant prospective validation, especially with the increasing evidence-based use of antiinflammatory therapy in acute lung injury. However, there are several important limitations to consider, including a small sample size from a single institution that precludes any definitive conclusions regarding any negative associations. Moreover, the single time point studied (the day of initiation of mechanical ventilation) and absence of a comparator group do not allow a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of antiinflammatory therapies across the trajectory of disease. Whether the findings are generalizable to all patients with ARDS treated with immunomodulators also remains unknown.

Overall, these data suggest that circulating signatures previously associated with ARDS, particularly those related to systemic inflammation, may have limited prognostic utility in the era of increasing immunomodulator use in critical illness. A deeper understanding of the pathobiology of ARDS, including the complex interplay with systemic immunomodulation, is needed to identify prognostic biomarkers and targeted therapies that improve patient outcomes.

Both authors work in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, in Boston.

References

1. Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al; RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704.

2. Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, et al. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1-11.

3. Dequin P-F, Meziani F, Quenot J-P, et al. Hydrocortisone in severe community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1931-1941.

4. Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang H-H, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1636-1643.

5. Alladina JW, Giacona FL, Haring AM, et al. Circulating biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction associated with ventilatory ratio and mortality in ARDS resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection treated with antiinflammatory therapies. CHEST Crit Care. 2024;2(2):100054.

6. Alba GA, Samokhin AO, Wang R-S, et al. NEDD9 is a novel and modifiable mediator of platelet-endothelial adhesion in the pulmonary circulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(12):1533-1545.

7. Alba GA, Samokhin AO, Wang R-S, et al. Pulmonary endothelial NEDD9 and the prothrombotic pathophenotype of acute respiratory distress syndrome due to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Pulm Circ. 2022;12(2):e12071.

The language of AI and its applications in health care

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

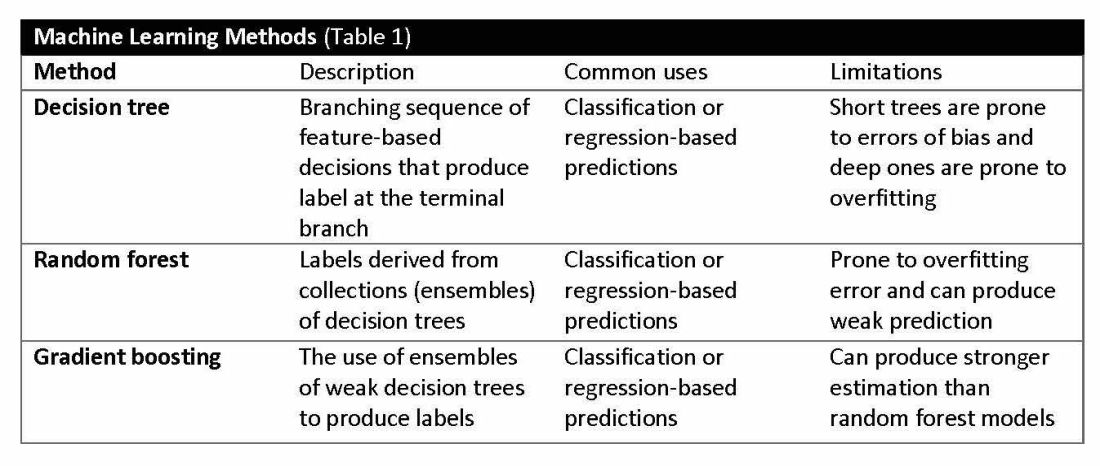

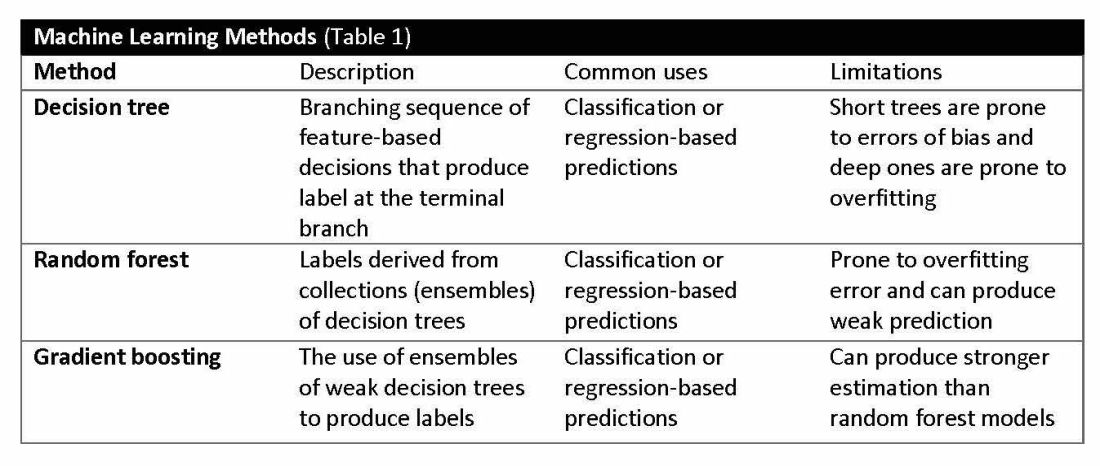

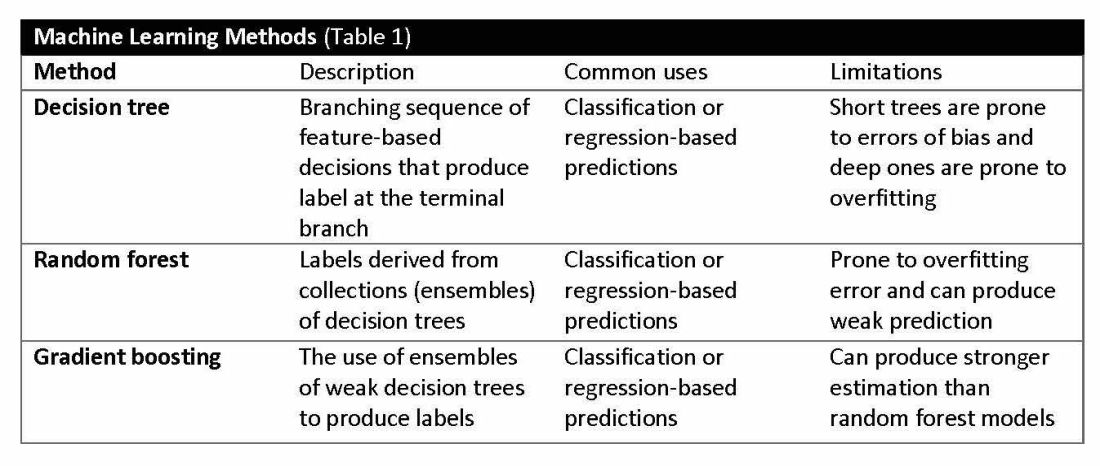

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

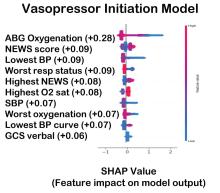

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

AI is a group of nonhuman techniques that utilize automated learning methods to extract information from datasets through generalization, classification, prediction, and association. In other words, AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. The branches of AI include natural language processing, speech recognition, machine vision, and expert systems. AI can make clinical care more efficient; however, many find its confusing terminology to be a barrier.1 This article provides concise definitions of AI terms and is intended to help physicians better understand how AI methods can be applied to clinical care. The clinical application of natural language processing and machine vision applications are more clinically intuitive than the roles of machine learning algorithms.

Machine learning and algorithms

Machine learning is a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic human reasoning through classification, pattern recognition, and prediction. Supervised and unsupervised machine-learning algorithms can analyze data and recognize undetected associations and relationships.

Supervised learning involves training models to make predictions using data sets that have correct outcome parameters called labels using predictive fields called features. Machine learning uses iterative analysis including random forest, decision tree, and gradient boosting methods that minimize predictive error metrics (see Table 1). This approach is widely used to improve diagnoses, predict disease progression or exacerbation, and personalize treatment plan modifications.

Supervised machine learning methods can be particularly effective for processing large volumes of medical information to identify patterns and make accurate predictions. In contrast, unsupervised learning techniques can analyze unlabeled data and help clinicians uncover hidden patterns or undetected groupings. Techniques including clustering, exploratory analysis, and anomaly detection are common applications. Both of these machine-learning approaches can be used to extract novel and helpful insights.

The utility of machine learning analyses depends on the size and accuracy of the available datasets. Small datasets can limit usability, while large datasets require substantial computational power. Predictive models are generated using training datasets and evaluated using separate evaluation datasets. Deep learning models, a subset of machine learning, can automatically readjust themselves to maintain or improve accuracy when analyzing new observations that include accurate labels.

Challenges of algorithms and calibration

Machine learning algorithms vary in complexity and accuracy. For example, a simple logistic regression model using time, date, latitude, and indoor/outdoor location can accurately recommend sunscreen application. This model identifies when solar radiation is high enough to warrant sunscreen use, avoiding unnecessary recommendations during nighttime hours or indoor locations. A more complex model might suffer from model overfitting and inappropriately suggest sunscreen before a tanning salon visit.

Complex machine learning models, like support vector machine (SVM) and decision tree methods, are useful when many features have predictive power. SVMs are useful for small but complex datasets. Features are manipulated in a multidimensional space to maximize the “margins” separating 2 groups. Decision tree analyses are useful when more than 2 groups are being analyzed. SVM and decision tree models can also lose accuracy by data overfitting.

Consider the development of an SVM analysis to predict whether an individual is a fellow or a senior faculty member. One could use high gray hair density feature values to identify senior faculty. When this algorithm is applied to an individual with alopecia, no amount of model adjustment can achieve high levels of discrimination because no hair is present. Rather than overfitting the model by adding more nonpredictive features, individuals with alopecia are analyzed by their own algorithm (tree) that uses the skin wrinkle/solar damage rather than the gray hair density feature.

Decision tree ensemble algorithms like random forest and gradient boosting use feature-based decision trees to process and classify data. Random forests are robust, scalable, and versatile, providing classifications and predictions while protecting against inaccurate data and outliers and have the advantage of being able to handle both categorical and continuous features. Gradient boosting, which uses an ensemble of weak decision trees, often outperforms random forests when individual trees perform only slightly better than random chance. This method incrementally builds the model by optimizing the residual errors of previous trees, leading to more accurate predictions.

In practice, gradient boosting can be used to fine-tune diagnostic models, improving their precision and reliability. A recent example of how gradient boosting of random forest predictions yielded highly accurate predictions for unplanned vasopressor initiation and intubation events 2 to 4 hours before an ICU adult became unstable.2

Assessing the accuracy of algorithms

The value of the data set is directly related to the accuracy of its labels. Traditional methods that measure model performance, such as sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values (PPV and NPV), have important limitations. They provide little insight into how a complex model made its prediction. Understanding which individual features drive model accuracy is key to fostering trust in model predictions. This can be done by comparing model output with and without including individual features. The results of all possible combinations are aggregated according to feature importance, which is summarized in the Shapley value for each model feature. Higher values indicate greater relative importance. SHAP plots help identify how much and how often specific features change the model output, presenting values of individual model estimates with and without a specific feature (see Figure 1).

Promoting AI use

AI and machine learning algorithms are coming to patient care. Understanding the language of AI helps caregivers integrate these tools into their practices. The science of AI faces serious challenges. Algorithms must be recalibrated to keep pace as therapies advance, disease prevalence changes, and our population ages. AI must address new challenges as they confront those suffering from respiratory diseases. This resource encourages clinicians with novel approaches by using AI methodologies to advance their development. We can better address future health care needs by promoting the equitable use of AI technologies, especially among socially disadvantaged developers.

References

1. Lilly CM, Soni AV, Dunlap D, et al. Advancing point of care testing by application of machine learning techniques and artificial intelligence. Chest. 2024 (in press).

2. Lilly CM, Kirk D, Pessach IM, et al. Application of machine learning models to biomedical and information system signals from critically ill adults. Chest. 2024;165(5):1139-1148.

Use of albumin in critically ill patients

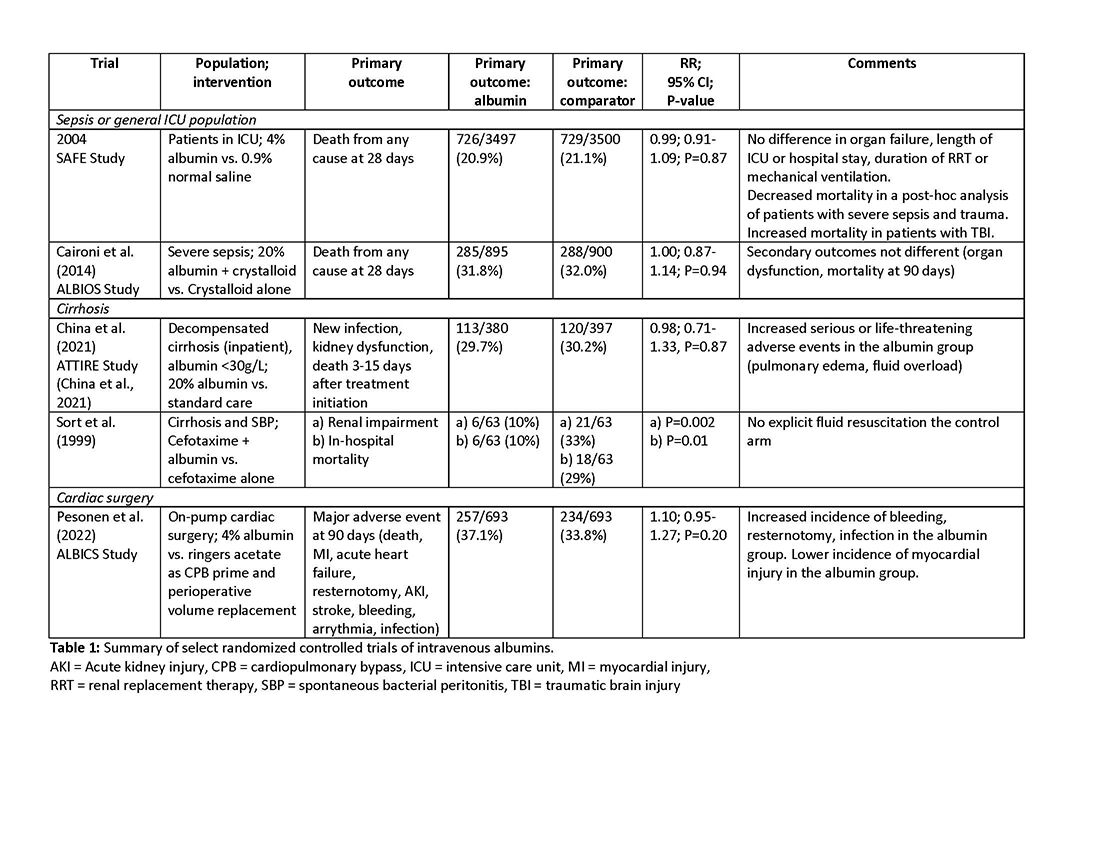

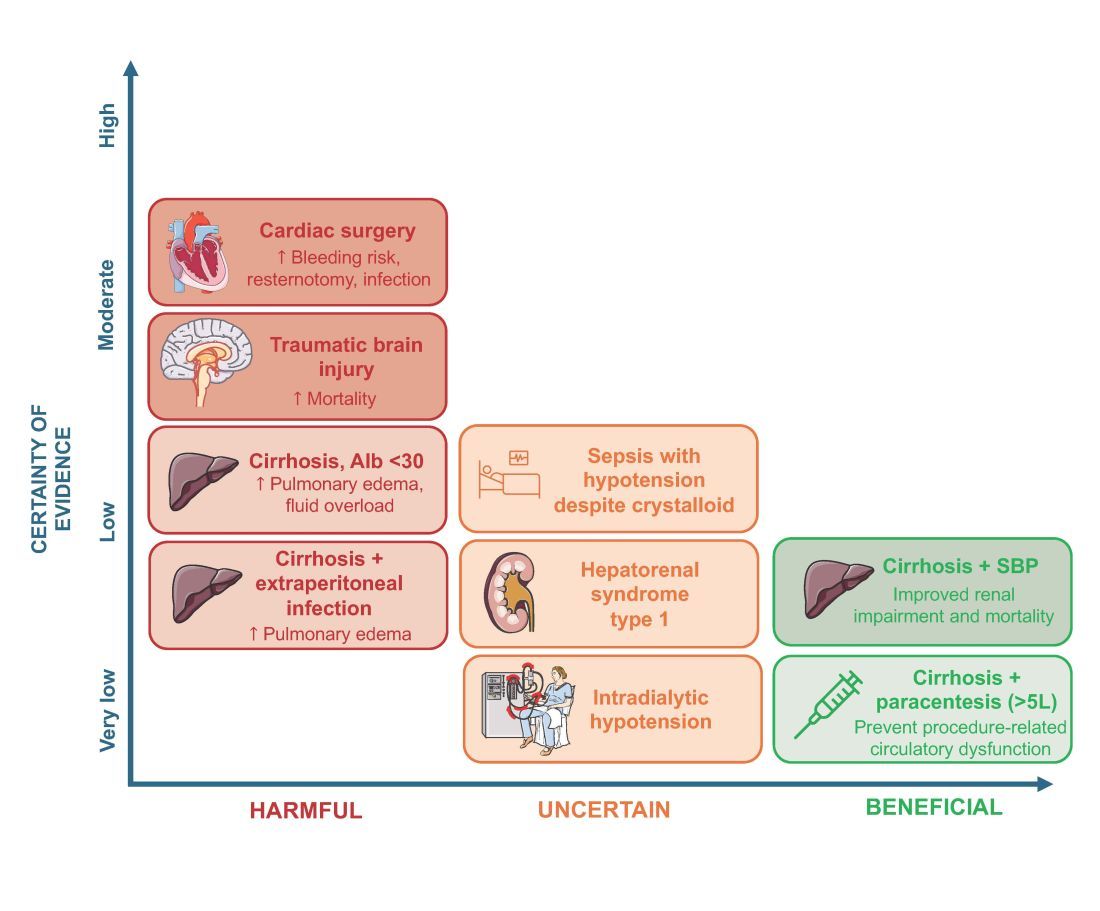

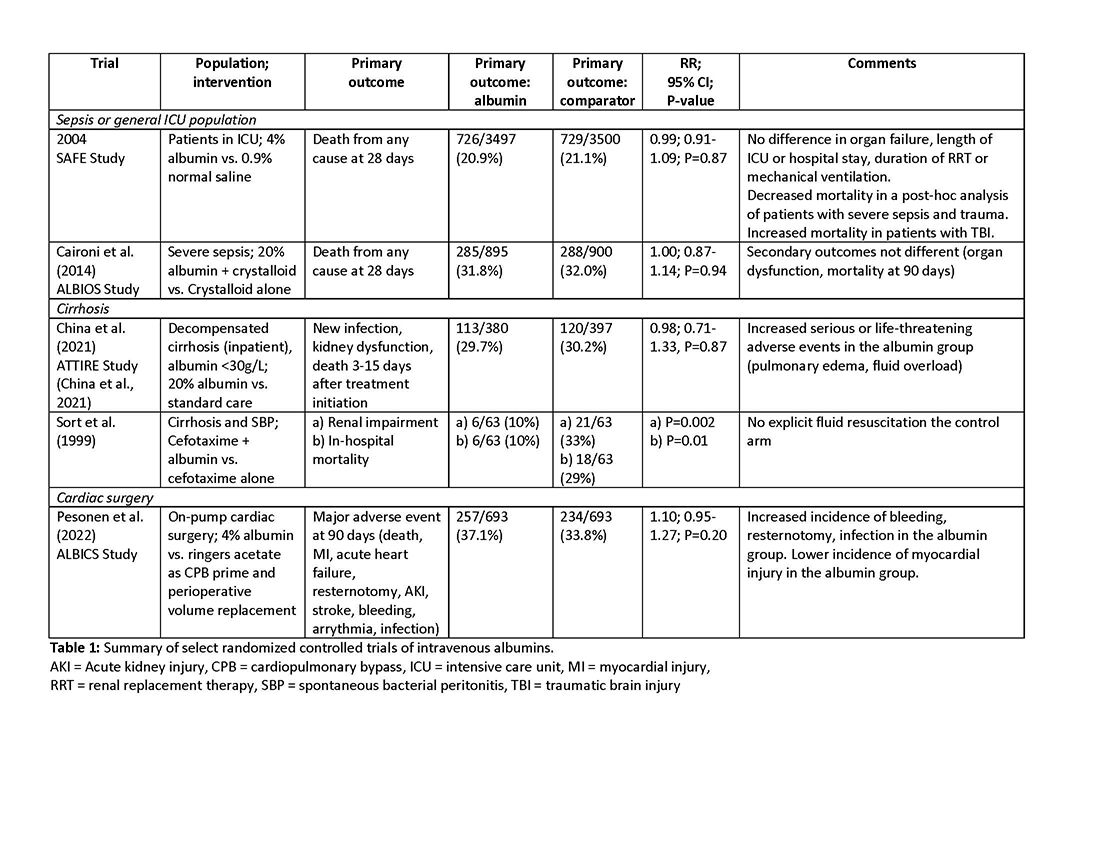

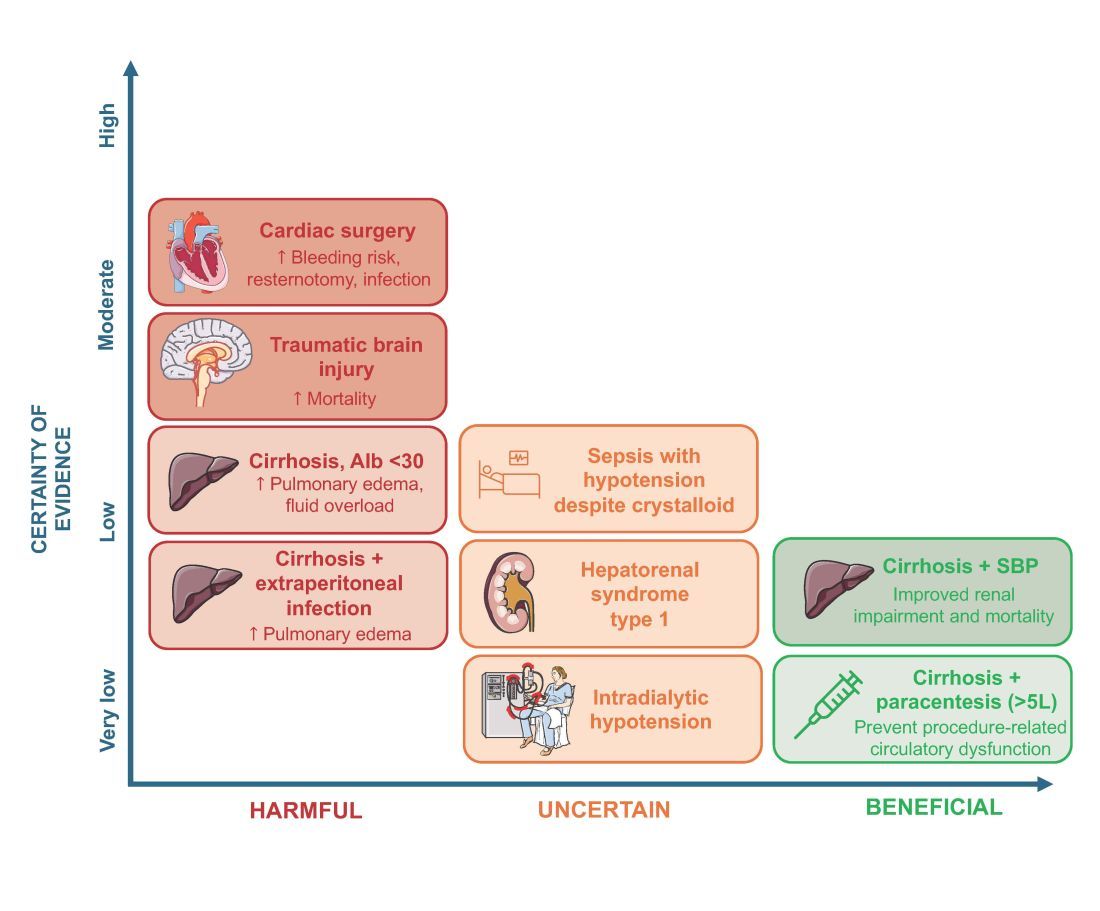

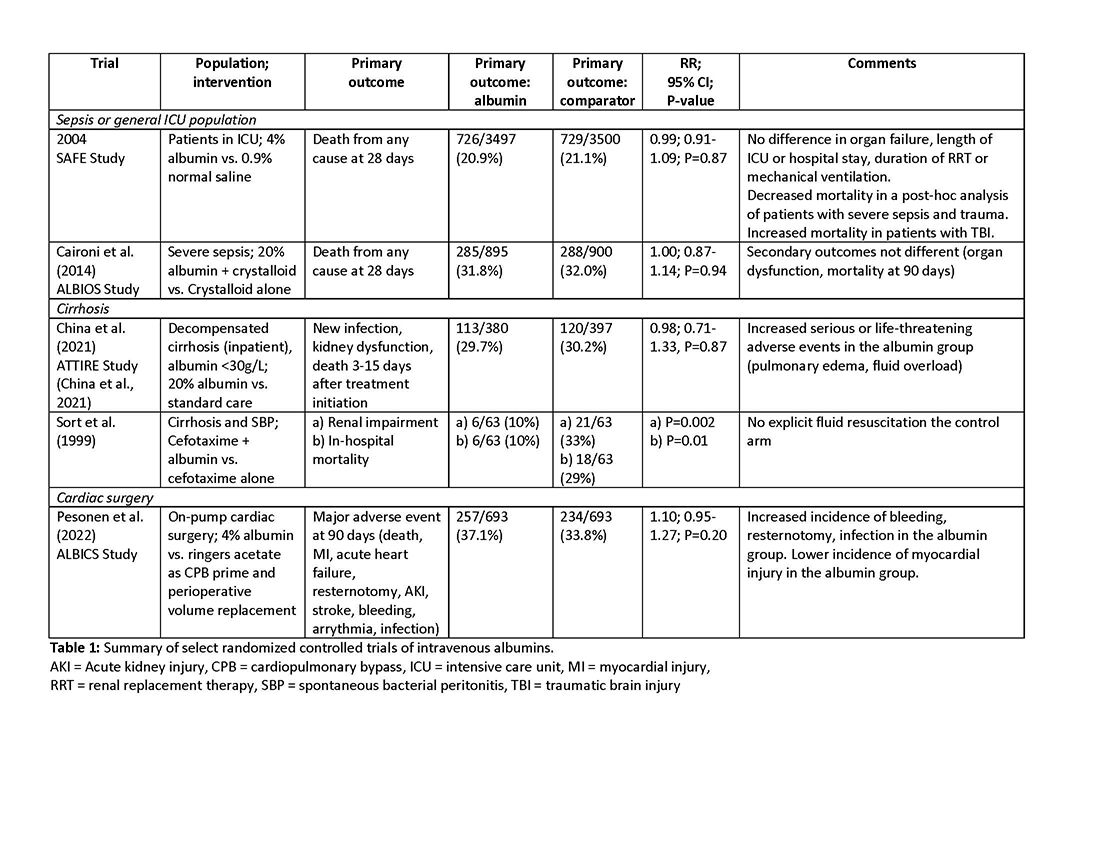

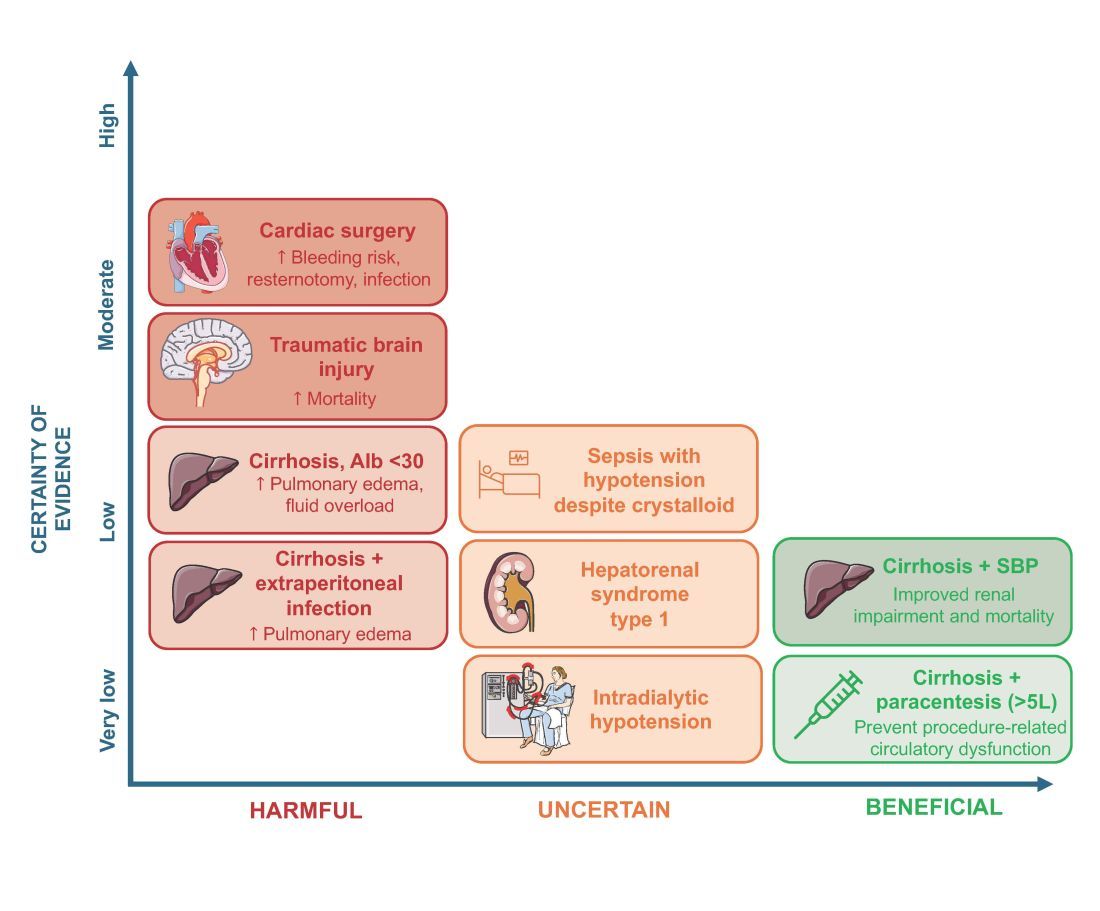

Intravenous albumin is a human-derived blood product studied widely in a variety of patient populations. Despite its frequent use in critical care, few high-quality studies have demonstrated improvements in patient-important outcomes. Compared with crystalloids, albumin increases the risk of fluid overload and bleeding and infections in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.1,2 In addition, albumin is costly, and its production is fraught with donor supply chain ethical concerns (the majority of albumin is derived from paid plasma donors).

Albumin use is highly variable between countries, hospitals, and even clinicians within the same specialty due to several factors, including the perception of minimal risk with albumin, concerns regarding insufficient short-term hemodynamic response to crystalloid, and lack of high-quality evidence to inform clinical practice. We will discuss when intensivists should consider albumin use (with prescription personalized to patient context) and when it should be avoided due to the concerns for patient harm.

An intensivist might consider albumin as a reasonable treatment option in patients with cirrhosis undergoing large volume paracentesis to prevent paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction, and in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), as data suggests use in this setting leads to a reduction in mortality.3 Clinicians should be aware that even for these widely accepted albumin indications, which are supported by published guidelines, the certainty of evidence is low, recommendations are weak (conditional), and, therefore, albumin should always be personalized to the patient based on volume of paracentesis fluid removed, prior history of hypotension after procedures, and degree of renal dysfunction.4

There are also several conditions for which an intensivist might consider albumin and for which albumin is commonly administered but lacks high-quality studies to support its use either as a frontline or rescue fluid therapy. One such condition is type 1 hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), for which albumin is widely used; however, there are no randomized controlled trials that have compared albumin with placebo.

As with any intervention, the use of albumin is associated with risks. In patients undergoing on-pump cardiac surgery, the ALBICS study showed that albumin did not reduce the risk of major adverse events and, instead, increased risk of bleeding, resternotomy, and infection.2 The ATTIRE trial showed that in patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis and serum albumin <30 g/L, albumin failed to reduce infection, renal impairment, or mortality while increasing life-threatening adverse events, including pulmonary edema and fluid overload.1 Similarly, in patients with cirrhosis and extraperitoneal infections, albumin showed no benefit in reducing renal impairment or mortality, and its use was associated with higher rates of pulmonary edema.6 Lastly, critically ill patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who received fluid resuscitation with albumin have been shown to experience higher mortality compared with saline.7 Thus, based on current evidence, intravenous albumin is not recommended for patients undergoing cardiac surgery (priming of the bypass circuit or volume replacement), patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis and hypoalbuminemia, patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and extraperitoneal infections, and critically ill patients with TBI.4

Overall, intravenous albumin prescription in critical care patients requires a personalized approach informed by current best evidence and is not without potential harm.

High-quality evidence is currently lacking in many clinical settings, and large randomized controlled trials are underway to provide further insights into the utility of albumin. These trials will address albumin use in the following: acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (ALTER-AKI, NCT04705896), inpatients with community-acquired pneumonia (NCT04071041), high-risk cardiac surgery (ACTRN1261900135516703), and septic shock (NCT03869385).

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures

Nicole Relke: None. Mark Hewitt: None. Bram Rochwerg: None. Jeannie Callum: Research support from Canadian Blood Services and Octapharma.

References

1. China L, Freemantle N, Forrest E, et al. A randomized trial of albumin infusions in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):808-817. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022166

2. Pesonen E, Vlasov H, Suojaranta R, et al. Effect of 4% albumin solution vs ringer acetate on major adverse events in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;328(3):251-258. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10461

3. Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. NEJM. 1999;341:403-409.

4. Callum J, Skubas NJ, Bathla A, et al. Use of intravenous albumin: a guideline from the international collaboration for transfusion medicine guidelines. Chest. 2024:S0012-3692(24)00285-X. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2024.02.049

5. Torp N. High doses of albumin increases mortality and complications in terlipressin treated patients with cirrhosis: insights from the ATTIRE trial. Paper presented at the AASLD; 2023; San Diego, CA. https://www.aasld.org/the-liver-meeting/high-doses-albumin-increases-mortality-and-complications-terlipressin-treated

6. Wong YJ, Qiu TY, Tam YC, Mohan BP, Gallegos-Orozco JF, Adler DG. Efficacy and safety of IV albumin for non-spontaneous bacterial peritonitis infection among patients with cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(10):1137-1142. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.047

7. Myburgh J, Cooper JD, Finfer S, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(9):874-884.

Intravenous albumin is a human-derived blood product studied widely in a variety of patient populations. Despite its frequent use in critical care, few high-quality studies have demonstrated improvements in patient-important outcomes. Compared with crystalloids, albumin increases the risk of fluid overload and bleeding and infections in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.1,2 In addition, albumin is costly, and its production is fraught with donor supply chain ethical concerns (the majority of albumin is derived from paid plasma donors).

Albumin use is highly variable between countries, hospitals, and even clinicians within the same specialty due to several factors, including the perception of minimal risk with albumin, concerns regarding insufficient short-term hemodynamic response to crystalloid, and lack of high-quality evidence to inform clinical practice. We will discuss when intensivists should consider albumin use (with prescription personalized to patient context) and when it should be avoided due to the concerns for patient harm.

An intensivist might consider albumin as a reasonable treatment option in patients with cirrhosis undergoing large volume paracentesis to prevent paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction, and in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), as data suggests use in this setting leads to a reduction in mortality.3 Clinicians should be aware that even for these widely accepted albumin indications, which are supported by published guidelines, the certainty of evidence is low, recommendations are weak (conditional), and, therefore, albumin should always be personalized to the patient based on volume of paracentesis fluid removed, prior history of hypotension after procedures, and degree of renal dysfunction.4

There are also several conditions for which an intensivist might consider albumin and for which albumin is commonly administered but lacks high-quality studies to support its use either as a frontline or rescue fluid therapy. One such condition is type 1 hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), for which albumin is widely used; however, there are no randomized controlled trials that have compared albumin with placebo.

As with any intervention, the use of albumin is associated with risks. In patients undergoing on-pump cardiac surgery, the ALBICS study showed that albumin did not reduce the risk of major adverse events and, instead, increased risk of bleeding, resternotomy, and infection.2 The ATTIRE trial showed that in patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis and serum albumin <30 g/L, albumin failed to reduce infection, renal impairment, or mortality while increasing life-threatening adverse events, including pulmonary edema and fluid overload.1 Similarly, in patients with cirrhosis and extraperitoneal infections, albumin showed no benefit in reducing renal impairment or mortality, and its use was associated with higher rates of pulmonary edema.6 Lastly, critically ill patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who received fluid resuscitation with albumin have been shown to experience higher mortality compared with saline.7 Thus, based on current evidence, intravenous albumin is not recommended for patients undergoing cardiac surgery (priming of the bypass circuit or volume replacement), patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis and hypoalbuminemia, patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and extraperitoneal infections, and critically ill patients with TBI.4

Overall, intravenous albumin prescription in critical care patients requires a personalized approach informed by current best evidence and is not without potential harm.

High-quality evidence is currently lacking in many clinical settings, and large randomized controlled trials are underway to provide further insights into the utility of albumin. These trials will address albumin use in the following: acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (ALTER-AKI, NCT04705896), inpatients with community-acquired pneumonia (NCT04071041), high-risk cardiac surgery (ACTRN1261900135516703), and septic shock (NCT03869385).

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures

Nicole Relke: None. Mark Hewitt: None. Bram Rochwerg: None. Jeannie Callum: Research support from Canadian Blood Services and Octapharma.

References

1. China L, Freemantle N, Forrest E, et al. A randomized trial of albumin infusions in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):808-817. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022166

2. Pesonen E, Vlasov H, Suojaranta R, et al. Effect of 4% albumin solution vs ringer acetate on major adverse events in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;328(3):251-258. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10461

3. Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. NEJM. 1999;341:403-409.

4. Callum J, Skubas NJ, Bathla A, et al. Use of intravenous albumin: a guideline from the international collaboration for transfusion medicine guidelines. Chest. 2024:S0012-3692(24)00285-X. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2024.02.049

5. Torp N. High doses of albumin increases mortality and complications in terlipressin treated patients with cirrhosis: insights from the ATTIRE trial. Paper presented at the AASLD; 2023; San Diego, CA. https://www.aasld.org/the-liver-meeting/high-doses-albumin-increases-mortality-and-complications-terlipressin-treated

6. Wong YJ, Qiu TY, Tam YC, Mohan BP, Gallegos-Orozco JF, Adler DG. Efficacy and safety of IV albumin for non-spontaneous bacterial peritonitis infection among patients with cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(10):1137-1142. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.047

7. Myburgh J, Cooper JD, Finfer S, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(9):874-884.

Intravenous albumin is a human-derived blood product studied widely in a variety of patient populations. Despite its frequent use in critical care, few high-quality studies have demonstrated improvements in patient-important outcomes. Compared with crystalloids, albumin increases the risk of fluid overload and bleeding and infections in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.1,2 In addition, albumin is costly, and its production is fraught with donor supply chain ethical concerns (the majority of albumin is derived from paid plasma donors).

Albumin use is highly variable between countries, hospitals, and even clinicians within the same specialty due to several factors, including the perception of minimal risk with albumin, concerns regarding insufficient short-term hemodynamic response to crystalloid, and lack of high-quality evidence to inform clinical practice. We will discuss when intensivists should consider albumin use (with prescription personalized to patient context) and when it should be avoided due to the concerns for patient harm.

An intensivist might consider albumin as a reasonable treatment option in patients with cirrhosis undergoing large volume paracentesis to prevent paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction, and in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), as data suggests use in this setting leads to a reduction in mortality.3 Clinicians should be aware that even for these widely accepted albumin indications, which are supported by published guidelines, the certainty of evidence is low, recommendations are weak (conditional), and, therefore, albumin should always be personalized to the patient based on volume of paracentesis fluid removed, prior history of hypotension after procedures, and degree of renal dysfunction.4

There are also several conditions for which an intensivist might consider albumin and for which albumin is commonly administered but lacks high-quality studies to support its use either as a frontline or rescue fluid therapy. One such condition is type 1 hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), for which albumin is widely used; however, there are no randomized controlled trials that have compared albumin with placebo.

As with any intervention, the use of albumin is associated with risks. In patients undergoing on-pump cardiac surgery, the ALBICS study showed that albumin did not reduce the risk of major adverse events and, instead, increased risk of bleeding, resternotomy, and infection.2 The ATTIRE trial showed that in patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis and serum albumin <30 g/L, albumin failed to reduce infection, renal impairment, or mortality while increasing life-threatening adverse events, including pulmonary edema and fluid overload.1 Similarly, in patients with cirrhosis and extraperitoneal infections, albumin showed no benefit in reducing renal impairment or mortality, and its use was associated with higher rates of pulmonary edema.6 Lastly, critically ill patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who received fluid resuscitation with albumin have been shown to experience higher mortality compared with saline.7 Thus, based on current evidence, intravenous albumin is not recommended for patients undergoing cardiac surgery (priming of the bypass circuit or volume replacement), patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis and hypoalbuminemia, patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and extraperitoneal infections, and critically ill patients with TBI.4

Overall, intravenous albumin prescription in critical care patients requires a personalized approach informed by current best evidence and is not without potential harm.

High-quality evidence is currently lacking in many clinical settings, and large randomized controlled trials are underway to provide further insights into the utility of albumin. These trials will address albumin use in the following: acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (ALTER-AKI, NCT04705896), inpatients with community-acquired pneumonia (NCT04071041), high-risk cardiac surgery (ACTRN1261900135516703), and septic shock (NCT03869385).

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures

Nicole Relke: None. Mark Hewitt: None. Bram Rochwerg: None. Jeannie Callum: Research support from Canadian Blood Services and Octapharma.

References

1. China L, Freemantle N, Forrest E, et al. A randomized trial of albumin infusions in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):808-817. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022166

2. Pesonen E, Vlasov H, Suojaranta R, et al. Effect of 4% albumin solution vs ringer acetate on major adverse events in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;328(3):251-258. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.10461

3. Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. NEJM. 1999;341:403-409.

4. Callum J, Skubas NJ, Bathla A, et al. Use of intravenous albumin: a guideline from the international collaboration for transfusion medicine guidelines. Chest. 2024:S0012-3692(24)00285-X. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2024.02.049

5. Torp N. High doses of albumin increases mortality and complications in terlipressin treated patients with cirrhosis: insights from the ATTIRE trial. Paper presented at the AASLD; 2023; San Diego, CA. https://www.aasld.org/the-liver-meeting/high-doses-albumin-increases-mortality-and-complications-terlipressin-treated

6. Wong YJ, Qiu TY, Tam YC, Mohan BP, Gallegos-Orozco JF, Adler DG. Efficacy and safety of IV albumin for non-spontaneous bacterial peritonitis infection among patients with cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(10):1137-1142. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.047

7. Myburgh J, Cooper JD, Finfer S, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(9):874-884.

Hospital-onset sepsis: Why the brouhaha?

A 47-year-old woman with a history of cirrhosis is admitted with an acute kidney injury and altered mental status. On the initial workup, there are no signs of infection, and dehydration is determined to be the cause of the kidney injury. There are signs of improvement in the kidney injury with hydration. On hospital day 3, the patient develops a fever (101.9 oF) with accompanying leukocytosis to 14,000. Concerned for infection, the team starts empiric broad spectrum antibiotics for presumed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The next day (hospital day 4), a rapid response evaluation is activated as the patient is demonstrating increasing confusion, hypotension with a systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg, and elevated lactic acid. The patient receives 1 L of normal saline and transfers to the ICU. The new critical care fellow, who has just read up on sepsis early management bundles, and specifically the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Management Bundle (SEP-1), is reviewing the chart and notices a history of multidrug-resistant organisms in her urine cultures from an admission 2 months ago. They ask of the transferring team, “When was time zero, and was the 3-hour bundle completed?”

1 The excessive cost, both of human life and monetary, has led to the commitment of significant resources to sepsis care. Improved recognition and timely intervention for sepsis have led to noteworthy improvement in mortality. Most of this effort has been directed toward patients with sepsis diagnosed in the emergency department (ED) who are presenting with community-onset sepsis (COS). A new entity, called hospital-onset sepsis (HOS), has been described recently, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as both infection and organ dysfunction developing more than 48 hours after hospital admission.2

A systematic review of 51 studies found approximately 23.6% of all sepsis cases are HOS. The proportion of HOS is even higher (more than 45%) in patients admitted to the ICU with sepsis.3 The outcome for this group remains comparatively poor. The hospital mortality among patients with HOS is 35%, which increases to 52% with progression to septic shock compared with 25% with COS.3 Even after adjusting for baseline factors that make one prone to developing infection in the hospital, a patient developing HOS has three-times a higher risk of dying compared with a patient who never developed sepsis and two-times a higher risk of dying compared with patients with COS.4Furthermore, HOS utilizes more resources with significantly longer ICU and hospital stays and has five-times the hospital cost compared with COS.4

The two most crucial factors in improving sepsis outcomes, as identified by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, are: 1) prompt identification and treatment within the first few hours of onset and 2) regular reevaluation of the patient’s response to treatment.

Prompt identification

Diagnosing sepsis in the patient who is hospitalized is challenging. Patients admitted to the hospital often have competing comorbidities, have existing organ failure, or are in a postoperative/intervention state that clouds the application and interpretation of vital sign triggers customarily used to identify sepsis. The positive predictive value for all existing sepsis definitions and diagnostic criteria is dismally low. 5 And while automated electronic sepsis alerts may improve processes of care, they still have poor positive predictive value and have not impacted patient-centered outcomes (mortality or length of stay). Furthermore, the causative microorganisms often associated with hospital-acquired infections are complex, are drug-resistant, and can have courses which further delay identification. Finally, cognitive errors, such as anchoring biases or premature diagnosis closure, can contribute to provider-level identification delays that are only further exacerbated by system issues, such as capacity constraints, staffing issues, and differing paces between wards that tend to impede time-sensitive evaluations and interventions. 4,6,7

Management

The SEP-1 core measure uses a framework of early recognition of infection and completion of the sepsis bundles in a timely manner to improve outcomes. Patients with HOS are less likely than those with COS to receive Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services SEP-1-compliant care, including timely blood culture collection, initial and repeat lactate testing, and fluid resuscitation.8 The Surviving Sepsis Campaign has explored barriers to managing HOS. Among caregivers, these include delay in recognition, poor communication regarding change in patient status, not prioritizing treatment for sepsis, failure to measure lactate, delayed or no antimicrobial administration, and inadequate fluid resuscitation. In one study, the adherence to SEP-1 for HOS was reported at 13% compared with 39.9% in COS. The differences in initial sepsis management included timing of antimicrobials and fluid resuscitation, which accounted for 23% of observed greater mortality risk among patients with HOS compared with COS.6,8 It remains unclear how these recommendations should be applied and whether some of these recommendations confer the same benefits for patients with HOS as for those with COS. For example, administration of fluids conferred no additional benefit to patients with HOS, while rapid antimicrobial administration was shown to be associated with improved mortality in patients with HOS. Although, the optimal timing for treatment initiation and microbial coverage has not been established.

The path forward

Effective HOS management requires both individual and systematic approaches. How clinicians identify a patient with sepsis must be context-dependent. Although standard criteria exist for defining sepsis, the approach to a patient presenting to the ED from home should differ from that of a patient who has been hospitalized for several days, is postoperative, or is in the ICU on multiple forms of life support. Clinical medicine is context-dependent, and the same principles apply to sepsis management. To address the diagnostic uncertainty of the syndrome, providers must remain vigilant and maintain a clinical “iterative urgency” in diagnosing and managing sepsis. While machine learning algorithms have potential, they still rely on human intervention and interaction to navigate the complexities of HOS diagnosis.

At the system level, survival from sepsis is determined by the speed with which complex medical care is delivered and the effectiveness with which resources and personnel are mobilized and coordinated. The Hospital Sepsis Program Core Elements, released by the CDC, serves as an initial playbook to aid hospitals in establishing comprehensive sepsis improvement programs.

A second invaluable resource for hospitals in sepsis management is the rapid response team (RRT). Studies have shown that resolute RRTs can enhance patient outcomes and compliance with sepsis bundles; though, the composition and scope of these teams are crucial to their effectiveness. Responding to in-hospital emergencies and urgencies without conflicting responsibilities is an essential feature of a successful RRT. Often, they are familiar with bundles, protocols, and documentation, and members of these teams can offer clinical and/or technical expertise as well as support active participation and reengagement with bedside staff, which fosters trust and collaboration. This partnership is key, as these interactions instill a common mission and foster a culture of sepsis improvement that is required to achieve sustained success and improved patient outcomes.

Dr. Dugar is Director, Point-of-Care Ultrasound, Department of Critical Care, Respiratory Institute, Assistant Professor, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, OH. Dr. Jayaprakash is Associate Medical Director, Quality, Emergency Medicine, Physician Lead, Henry Ford Health Sepsis Program. Dr. Reilkoff is Executive Medical Director of Critical Care, M Health Fairview Intensive Care Units, Director of Acting Internship in Critical Care, University of Minnesota Medical School, Associate Professor of Medicine and Surgery, University of Minnesota. Dr. Duggal is Vice-Chair, Department of Critical Care, Respiratory Institute, Director, Critical Care Clinical Research, Associate Professor, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, OH

References

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810.

2. Ginestra JC, Coz Yataco AO, Dugar SP, Dettmer MR. Hospital-onset sepsis warrants expanded investigation and consideration as a unique clinical entity. Chest. 2024;S0012-3692(24):00039-4.

3. Markwart R, Saito H, Harder T, et al. Epidemiology and burden of sepsis acquired in hospitals and intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(8):1536-1551.

4. Rhee C, Wang R, Zhang Z, et al. Epidemiology of hospital-onset versus community-onset sepsis in U.S. hospitals and association with mortality: a retrospective analysis using electronic clinical data. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(9):1169-1176.

5. Wong A, Otles E, Donnelly JP, et al. External validation of a widely implemented proprietary sepsis prediction model in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(8):1065-1070.

6. Baghdadi JD, Brook RH, Uslan DZ, et al. Association of a care bundle for early sepsis management with mortality among patients with hospital-onset or community-onset sepsis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):707-716.

7. Baghdadi JD, Wong MD, Uslan DZ, et al. Adherence to the SEP-1 sepsis bundle in hospital-onset v. community-onset sepsis: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):1153-1160.

8. Basheer A. Patients with hospital-onset sepsis are less likely to receive sepsis bundle care than those with community-onset sepsis. Evid Based Nurs. 2021;24(3):99.

A 47-year-old woman with a history of cirrhosis is admitted with an acute kidney injury and altered mental status. On the initial workup, there are no signs of infection, and dehydration is determined to be the cause of the kidney injury. There are signs of improvement in the kidney injury with hydration. On hospital day 3, the patient develops a fever (101.9 oF) with accompanying leukocytosis to 14,000. Concerned for infection, the team starts empiric broad spectrum antibiotics for presumed spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The next day (hospital day 4), a rapid response evaluation is activated as the patient is demonstrating increasing confusion, hypotension with a systolic blood pressure of 70 mm Hg, and elevated lactic acid. The patient receives 1 L of normal saline and transfers to the ICU. The new critical care fellow, who has just read up on sepsis early management bundles, and specifically the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Management Bundle (SEP-1), is reviewing the chart and notices a history of multidrug-resistant organisms in her urine cultures from an admission 2 months ago. They ask of the transferring team, “When was time zero, and was the 3-hour bundle completed?”

1 The excessive cost, both of human life and monetary, has led to the commitment of significant resources to sepsis care. Improved recognition and timely intervention for sepsis have led to noteworthy improvement in mortality. Most of this effort has been directed toward patients with sepsis diagnosed in the emergency department (ED) who are presenting with community-onset sepsis (COS). A new entity, called hospital-onset sepsis (HOS), has been described recently, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as both infection and organ dysfunction developing more than 48 hours after hospital admission.2

A systematic review of 51 studies found approximately 23.6% of all sepsis cases are HOS. The proportion of HOS is even higher (more than 45%) in patients admitted to the ICU with sepsis.3 The outcome for this group remains comparatively poor. The hospital mortality among patients with HOS is 35%, which increases to 52% with progression to septic shock compared with 25% with COS.3 Even after adjusting for baseline factors that make one prone to developing infection in the hospital, a patient developing HOS has three-times a higher risk of dying compared with a patient who never developed sepsis and two-times a higher risk of dying compared with patients with COS.4Furthermore, HOS utilizes more resources with significantly longer ICU and hospital stays and has five-times the hospital cost compared with COS.4

The two most crucial factors in improving sepsis outcomes, as identified by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, are: 1) prompt identification and treatment within the first few hours of onset and 2) regular reevaluation of the patient’s response to treatment.

Prompt identification

Diagnosing sepsis in the patient who is hospitalized is challenging. Patients admitted to the hospital often have competing comorbidities, have existing organ failure, or are in a postoperative/intervention state that clouds the application and interpretation of vital sign triggers customarily used to identify sepsis. The positive predictive value for all existing sepsis definitions and diagnostic criteria is dismally low. 5 And while automated electronic sepsis alerts may improve processes of care, they still have poor positive predictive value and have not impacted patient-centered outcomes (mortality or length of stay). Furthermore, the causative microorganisms often associated with hospital-acquired infections are complex, are drug-resistant, and can have courses which further delay identification. Finally, cognitive errors, such as anchoring biases or premature diagnosis closure, can contribute to provider-level identification delays that are only further exacerbated by system issues, such as capacity constraints, staffing issues, and differing paces between wards that tend to impede time-sensitive evaluations and interventions. 4,6,7

Management

The SEP-1 core measure uses a framework of early recognition of infection and completion of the sepsis bundles in a timely manner to improve outcomes. Patients with HOS are less likely than those with COS to receive Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services SEP-1-compliant care, including timely blood culture collection, initial and repeat lactate testing, and fluid resuscitation.8 The Surviving Sepsis Campaign has explored barriers to managing HOS. Among caregivers, these include delay in recognition, poor communication regarding change in patient status, not prioritizing treatment for sepsis, failure to measure lactate, delayed or no antimicrobial administration, and inadequate fluid resuscitation. In one study, the adherence to SEP-1 for HOS was reported at 13% compared with 39.9% in COS. The differences in initial sepsis management included timing of antimicrobials and fluid resuscitation, which accounted for 23% of observed greater mortality risk among patients with HOS compared with COS.6,8 It remains unclear how these recommendations should be applied and whether some of these recommendations confer the same benefits for patients with HOS as for those with COS. For example, administration of fluids conferred no additional benefit to patients with HOS, while rapid antimicrobial administration was shown to be associated with improved mortality in patients with HOS. Although, the optimal timing for treatment initiation and microbial coverage has not been established.

The path forward

Effective HOS management requires both individual and systematic approaches. How clinicians identify a patient with sepsis must be context-dependent. Although standard criteria exist for defining sepsis, the approach to a patient presenting to the ED from home should differ from that of a patient who has been hospitalized for several days, is postoperative, or is in the ICU on multiple forms of life support. Clinical medicine is context-dependent, and the same principles apply to sepsis management. To address the diagnostic uncertainty of the syndrome, providers must remain vigilant and maintain a clinical “iterative urgency” in diagnosing and managing sepsis. While machine learning algorithms have potential, they still rely on human intervention and interaction to navigate the complexities of HOS diagnosis.

At the system level, survival from sepsis is determined by the speed with which complex medical care is delivered and the effectiveness with which resources and personnel are mobilized and coordinated. The Hospital Sepsis Program Core Elements, released by the CDC, serves as an initial playbook to aid hospitals in establishing comprehensive sepsis improvement programs.

A second invaluable resource for hospitals in sepsis management is the rapid response team (RRT). Studies have shown that resolute RRTs can enhance patient outcomes and compliance with sepsis bundles; though, the composition and scope of these teams are crucial to their effectiveness. Responding to in-hospital emergencies and urgencies without conflicting responsibilities is an essential feature of a successful RRT. Often, they are familiar with bundles, protocols, and documentation, and members of these teams can offer clinical and/or technical expertise as well as support active participation and reengagement with bedside staff, which fosters trust and collaboration. This partnership is key, as these interactions instill a common mission and foster a culture of sepsis improvement that is required to achieve sustained success and improved patient outcomes.

Dr. Dugar is Director, Point-of-Care Ultrasound, Department of Critical Care, Respiratory Institute, Assistant Professor, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, OH. Dr. Jayaprakash is Associate Medical Director, Quality, Emergency Medicine, Physician Lead, Henry Ford Health Sepsis Program. Dr. Reilkoff is Executive Medical Director of Critical Care, M Health Fairview Intensive Care Units, Director of Acting Internship in Critical Care, University of Minnesota Medical School, Associate Professor of Medicine and Surgery, University of Minnesota. Dr. Duggal is Vice-Chair, Department of Critical Care, Respiratory Institute, Director, Critical Care Clinical Research, Associate Professor, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Cleveland, OH

References

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810.

2. Ginestra JC, Coz Yataco AO, Dugar SP, Dettmer MR. Hospital-onset sepsis warrants expanded investigation and consideration as a unique clinical entity. Chest. 2024;S0012-3692(24):00039-4.

3. Markwart R, Saito H, Harder T, et al. Epidemiology and burden of sepsis acquired in hospitals and intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(8):1536-1551.