User login

Bowel perforation causes woman’s death: $1.5M verdict

A 46-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy to remove her uterus but preserve her cervix. Postsurgically, she had difficulty breathing deeply and reported abdominal pain. The nurses and on-call physician reassured her that she was experiencing “gas pains” due to insufflation. After same-day discharge, she stayed in a motel room to avoid a second-floor bedroom at home.

She called the gynecologist’s office the following day to report continued pain and severe hot flashes and sweats. The gynecologist instructed his nurse to advise the patient to stop taking her birth control pill (ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone, Microgestin) and “to ride out” the hot flashes.

The woman was found dead in her motel room the next morning. An autopsy revealed a perforated small intestine with leakage into the abdominal cavity causing sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist reviewed the medical records and found an error in the operative report, but he made no addendum or late entry to correct the operative report. His defense counsel instructed him to draft a letter clarifying the surgery; this clarification was given to defense experts. The description of the procedure in the clarification was different from what was described in the medical records. For example, the clarification reported making 4 incisions for 4 trocars; the operative report indicated using 3 trocars. The pathologist and 2 nurses who treated the patient after surgery confirmed that there were 3 trocar incisions. The pathologist found no tissue necrosis at or around the perforation site, indicating that the perforation likely occurred during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Bowel perforation is a known complication of the procedure. The perforation was not present at the time of surgery because leakage of bowel content would have been obvious.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Retained products of conception after D&C

When sonography indicated that a 30-year-old woman was pregnant, she decided to abort the pregnancy and was given mifepristone.

Another sonogram 5 weeks later showed retained products of conception within the uterus. An ObGyn performed dilation and curettage (D&C) at an outpatient clinic. Because he believed the cannula did not remove everything, he used a curette to scrape the uterus. After the patient was dizzy, hypotensive, and in pain for 4 hours, an ambulance transported her to a hospital. Perforations of the uterus and sigmoid colon were discovered and repaired during emergency surgery. The patient has a large scar on her abdomen.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform the D&C properly and perforated the uterus and colon. An earlier response to symptoms could have prevented repair surgery. Damage to the uterus may now preclude her from having a successful pregnancy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that the aborted pregnancy was ectopic; spontaneous rupture caused the perforations.

VERDICT A $340,000 New York settlement was reached with the ObGyn. By the time of trial, the clinic had closed.

Wrong-site biopsy; records altered

A 40-year-old woman underwent excisional breast biopsy. The wrong lump was removed and the woman had to have another procedure.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The hospital’s nursing staff failed to properly mark the operative site. The breast surgeon did not confirm that the markings were correct. The surgeon altered the written operative report after the surgery to conceal negligence.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The nurses properly marked the biopsy site, but the surgeon chose another route. The surgeon edited the original report to reflect events that occurred during surgery that had not been included in the original dictation. The added material gave justification for performing the procedure at a different site than originally intended.

VERDICT A $15,500 Connecticut verdict was returned.

Second twin has CP and brain damage: $10M settlement

A woman gave birth to twins at an Army hospital. The first twin was delivered without complications. The second twin developed a prolapsed cord during delivery of the first twin. A resident and the attending physician allowed the mother to continue with vaginal delivery. The heart-rate monitor showed fetal distress, but the medical staff did not respond. After an hour, another physician was consulted, and he ordered immediate delivery. The attending physician decided to continue with vaginal delivery using forceps, but it took 15 minutes to locate forceps in the hospital. The infant suffered severe brain damage and cerebral palsy. She will require 24-hour nursing care for life, including treatment of a tracheostomy.

PARENTS' CLAIM The physicians were negligent for not reacting to non-reassuring monitor strips and for allowing the vaginal delivery to continue. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $10 million North Carolina settlement was reached for past medical bills and future care.

Faulty biopsies: breast cancer diagnosis missed

In September 2006, a 40-year-old woman underwent breast sonography. A radiologist, Dr. A, reported finding a mass and a smaller nodule in the right breast, and recommended a biopsy of each area. Two weeks later, a second radiologist, Dr. B, biopsied the larger of the two areas and diagnosed a hyalinized fibroadenoma. He did not biopsy the smaller growth, but reported it as a benign nodule. He recommended more frequent screenings. The patient was referred to a surgeon, who determined that she should be seen in 6 months.

In June 2007, the patient underwent right-breast sonography that revealed cysts and three nodules. The surgeon recommended a biopsy, but the biopsy was performed on only two of three nodules. A third radiologist, Dr. C, determined that the nodules were all benign.

In November 2007, when the patient reported a painful lump in her right breast, her gynecologist ordered mammography, which revealed lesions. A biopsy revealed that one lesion was stage III invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient underwent extensive treatment, including a mastectomy, lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, and prophylactic surgical reduction of the left breast.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The cancer should have been diagnosed in September 2006. Prompt treatment would have decreased the progression of the disease. The September 2006 biopsy should have included both lumps, as recommended by Dr. A.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no indication of cancer in September 2006. Reasonable follow-up care was given.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

Tumor not found during surgery; BSO performed

A 41-year-old woman underwent surgery to remove a pelvic tumor in November 2004. The gynecologist was unable to locate the tumor during surgery. He performed bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) because of a visual diagnosis of endometriosis. In August 2005, the patient underwent surgical removal of the tumor by another surgeon. She was hospitalized for several weeks and suffered a large scar that required additional surgery.

PATIENT'S CLAIM BSO was unnecessary, and caused early menopause, with vaginal atrophy and dryness, depression, fatigue, insomnia, loss of hair, and other symptoms.

The patient claimed lack of informed consent. From Ecuador, the patient’s command of English was not sufficient for her to completely understand the consent form; an interpreter should have been provided.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE BSO did not cause a significant acceleration of the onset of menopause. It was necessary to treat the endometriosis.

The patient signed a consent form that included BSO. The patient did not indicate that she did not understand the language on the form; had she asked, an interpreter would have been provided.

VERDICT A $750,000 New York settlement was reached with the gynecologist and medical center.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

A 46-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy to remove her uterus but preserve her cervix. Postsurgically, she had difficulty breathing deeply and reported abdominal pain. The nurses and on-call physician reassured her that she was experiencing “gas pains” due to insufflation. After same-day discharge, she stayed in a motel room to avoid a second-floor bedroom at home.

She called the gynecologist’s office the following day to report continued pain and severe hot flashes and sweats. The gynecologist instructed his nurse to advise the patient to stop taking her birth control pill (ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone, Microgestin) and “to ride out” the hot flashes.

The woman was found dead in her motel room the next morning. An autopsy revealed a perforated small intestine with leakage into the abdominal cavity causing sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist reviewed the medical records and found an error in the operative report, but he made no addendum or late entry to correct the operative report. His defense counsel instructed him to draft a letter clarifying the surgery; this clarification was given to defense experts. The description of the procedure in the clarification was different from what was described in the medical records. For example, the clarification reported making 4 incisions for 4 trocars; the operative report indicated using 3 trocars. The pathologist and 2 nurses who treated the patient after surgery confirmed that there were 3 trocar incisions. The pathologist found no tissue necrosis at or around the perforation site, indicating that the perforation likely occurred during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Bowel perforation is a known complication of the procedure. The perforation was not present at the time of surgery because leakage of bowel content would have been obvious.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Retained products of conception after D&C

When sonography indicated that a 30-year-old woman was pregnant, she decided to abort the pregnancy and was given mifepristone.

Another sonogram 5 weeks later showed retained products of conception within the uterus. An ObGyn performed dilation and curettage (D&C) at an outpatient clinic. Because he believed the cannula did not remove everything, he used a curette to scrape the uterus. After the patient was dizzy, hypotensive, and in pain for 4 hours, an ambulance transported her to a hospital. Perforations of the uterus and sigmoid colon were discovered and repaired during emergency surgery. The patient has a large scar on her abdomen.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform the D&C properly and perforated the uterus and colon. An earlier response to symptoms could have prevented repair surgery. Damage to the uterus may now preclude her from having a successful pregnancy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that the aborted pregnancy was ectopic; spontaneous rupture caused the perforations.

VERDICT A $340,000 New York settlement was reached with the ObGyn. By the time of trial, the clinic had closed.

Wrong-site biopsy; records altered

A 40-year-old woman underwent excisional breast biopsy. The wrong lump was removed and the woman had to have another procedure.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The hospital’s nursing staff failed to properly mark the operative site. The breast surgeon did not confirm that the markings were correct. The surgeon altered the written operative report after the surgery to conceal negligence.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The nurses properly marked the biopsy site, but the surgeon chose another route. The surgeon edited the original report to reflect events that occurred during surgery that had not been included in the original dictation. The added material gave justification for performing the procedure at a different site than originally intended.

VERDICT A $15,500 Connecticut verdict was returned.

Second twin has CP and brain damage: $10M settlement

A woman gave birth to twins at an Army hospital. The first twin was delivered without complications. The second twin developed a prolapsed cord during delivery of the first twin. A resident and the attending physician allowed the mother to continue with vaginal delivery. The heart-rate monitor showed fetal distress, but the medical staff did not respond. After an hour, another physician was consulted, and he ordered immediate delivery. The attending physician decided to continue with vaginal delivery using forceps, but it took 15 minutes to locate forceps in the hospital. The infant suffered severe brain damage and cerebral palsy. She will require 24-hour nursing care for life, including treatment of a tracheostomy.

PARENTS' CLAIM The physicians were negligent for not reacting to non-reassuring monitor strips and for allowing the vaginal delivery to continue. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $10 million North Carolina settlement was reached for past medical bills and future care.

Faulty biopsies: breast cancer diagnosis missed

In September 2006, a 40-year-old woman underwent breast sonography. A radiologist, Dr. A, reported finding a mass and a smaller nodule in the right breast, and recommended a biopsy of each area. Two weeks later, a second radiologist, Dr. B, biopsied the larger of the two areas and diagnosed a hyalinized fibroadenoma. He did not biopsy the smaller growth, but reported it as a benign nodule. He recommended more frequent screenings. The patient was referred to a surgeon, who determined that she should be seen in 6 months.

In June 2007, the patient underwent right-breast sonography that revealed cysts and three nodules. The surgeon recommended a biopsy, but the biopsy was performed on only two of three nodules. A third radiologist, Dr. C, determined that the nodules were all benign.

In November 2007, when the patient reported a painful lump in her right breast, her gynecologist ordered mammography, which revealed lesions. A biopsy revealed that one lesion was stage III invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient underwent extensive treatment, including a mastectomy, lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, and prophylactic surgical reduction of the left breast.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The cancer should have been diagnosed in September 2006. Prompt treatment would have decreased the progression of the disease. The September 2006 biopsy should have included both lumps, as recommended by Dr. A.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no indication of cancer in September 2006. Reasonable follow-up care was given.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

Tumor not found during surgery; BSO performed

A 41-year-old woman underwent surgery to remove a pelvic tumor in November 2004. The gynecologist was unable to locate the tumor during surgery. He performed bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) because of a visual diagnosis of endometriosis. In August 2005, the patient underwent surgical removal of the tumor by another surgeon. She was hospitalized for several weeks and suffered a large scar that required additional surgery.

PATIENT'S CLAIM BSO was unnecessary, and caused early menopause, with vaginal atrophy and dryness, depression, fatigue, insomnia, loss of hair, and other symptoms.

The patient claimed lack of informed consent. From Ecuador, the patient’s command of English was not sufficient for her to completely understand the consent form; an interpreter should have been provided.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE BSO did not cause a significant acceleration of the onset of menopause. It was necessary to treat the endometriosis.

The patient signed a consent form that included BSO. The patient did not indicate that she did not understand the language on the form; had she asked, an interpreter would have been provided.

VERDICT A $750,000 New York settlement was reached with the gynecologist and medical center.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

A 46-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy to remove her uterus but preserve her cervix. Postsurgically, she had difficulty breathing deeply and reported abdominal pain. The nurses and on-call physician reassured her that she was experiencing “gas pains” due to insufflation. After same-day discharge, she stayed in a motel room to avoid a second-floor bedroom at home.

She called the gynecologist’s office the following day to report continued pain and severe hot flashes and sweats. The gynecologist instructed his nurse to advise the patient to stop taking her birth control pill (ethinyl estradiol/norethindrone, Microgestin) and “to ride out” the hot flashes.

The woman was found dead in her motel room the next morning. An autopsy revealed a perforated small intestine with leakage into the abdominal cavity causing sepsis, multi-organ failure, and death.

ESTATE’S CLAIM The gynecologist reviewed the medical records and found an error in the operative report, but he made no addendum or late entry to correct the operative report. His defense counsel instructed him to draft a letter clarifying the surgery; this clarification was given to defense experts. The description of the procedure in the clarification was different from what was described in the medical records. For example, the clarification reported making 4 incisions for 4 trocars; the operative report indicated using 3 trocars. The pathologist and 2 nurses who treated the patient after surgery confirmed that there were 3 trocar incisions. The pathologist found no tissue necrosis at or around the perforation site, indicating that the perforation likely occurred during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Bowel perforation is a known complication of the procedure. The perforation was not present at the time of surgery because leakage of bowel content would have been obvious.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Virginia settlement was reached.

Retained products of conception after D&C

When sonography indicated that a 30-year-old woman was pregnant, she decided to abort the pregnancy and was given mifepristone.

Another sonogram 5 weeks later showed retained products of conception within the uterus. An ObGyn performed dilation and curettage (D&C) at an outpatient clinic. Because he believed the cannula did not remove everything, he used a curette to scrape the uterus. After the patient was dizzy, hypotensive, and in pain for 4 hours, an ambulance transported her to a hospital. Perforations of the uterus and sigmoid colon were discovered and repaired during emergency surgery. The patient has a large scar on her abdomen.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform the D&C properly and perforated the uterus and colon. An earlier response to symptoms could have prevented repair surgery. Damage to the uterus may now preclude her from having a successful pregnancy.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The ObGyn argued that the aborted pregnancy was ectopic; spontaneous rupture caused the perforations.

VERDICT A $340,000 New York settlement was reached with the ObGyn. By the time of trial, the clinic had closed.

Wrong-site biopsy; records altered

A 40-year-old woman underwent excisional breast biopsy. The wrong lump was removed and the woman had to have another procedure.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The hospital’s nursing staff failed to properly mark the operative site. The breast surgeon did not confirm that the markings were correct. The surgeon altered the written operative report after the surgery to conceal negligence.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The nurses properly marked the biopsy site, but the surgeon chose another route. The surgeon edited the original report to reflect events that occurred during surgery that had not been included in the original dictation. The added material gave justification for performing the procedure at a different site than originally intended.

VERDICT A $15,500 Connecticut verdict was returned.

Second twin has CP and brain damage: $10M settlement

A woman gave birth to twins at an Army hospital. The first twin was delivered without complications. The second twin developed a prolapsed cord during delivery of the first twin. A resident and the attending physician allowed the mother to continue with vaginal delivery. The heart-rate monitor showed fetal distress, but the medical staff did not respond. After an hour, another physician was consulted, and he ordered immediate delivery. The attending physician decided to continue with vaginal delivery using forceps, but it took 15 minutes to locate forceps in the hospital. The infant suffered severe brain damage and cerebral palsy. She will require 24-hour nursing care for life, including treatment of a tracheostomy.

PARENTS' CLAIM The physicians were negligent for not reacting to non-reassuring monitor strips and for allowing the vaginal delivery to continue. An emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $10 million North Carolina settlement was reached for past medical bills and future care.

Faulty biopsies: breast cancer diagnosis missed

In September 2006, a 40-year-old woman underwent breast sonography. A radiologist, Dr. A, reported finding a mass and a smaller nodule in the right breast, and recommended a biopsy of each area. Two weeks later, a second radiologist, Dr. B, biopsied the larger of the two areas and diagnosed a hyalinized fibroadenoma. He did not biopsy the smaller growth, but reported it as a benign nodule. He recommended more frequent screenings. The patient was referred to a surgeon, who determined that she should be seen in 6 months.

In June 2007, the patient underwent right-breast sonography that revealed cysts and three nodules. The surgeon recommended a biopsy, but the biopsy was performed on only two of three nodules. A third radiologist, Dr. C, determined that the nodules were all benign.

In November 2007, when the patient reported a painful lump in her right breast, her gynecologist ordered mammography, which revealed lesions. A biopsy revealed that one lesion was stage III invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient underwent extensive treatment, including a mastectomy, lymphadenectomy, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, and prophylactic surgical reduction of the left breast.

PATIENT'S CLAIM The cancer should have been diagnosed in September 2006. Prompt treatment would have decreased the progression of the disease. The September 2006 biopsy should have included both lumps, as recommended by Dr. A.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE There was no indication of cancer in September 2006. Reasonable follow-up care was given.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

Tumor not found during surgery; BSO performed

A 41-year-old woman underwent surgery to remove a pelvic tumor in November 2004. The gynecologist was unable to locate the tumor during surgery. He performed bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) because of a visual diagnosis of endometriosis. In August 2005, the patient underwent surgical removal of the tumor by another surgeon. She was hospitalized for several weeks and suffered a large scar that required additional surgery.

PATIENT'S CLAIM BSO was unnecessary, and caused early menopause, with vaginal atrophy and dryness, depression, fatigue, insomnia, loss of hair, and other symptoms.

The patient claimed lack of informed consent. From Ecuador, the patient’s command of English was not sufficient for her to completely understand the consent form; an interpreter should have been provided.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE BSO did not cause a significant acceleration of the onset of menopause. It was necessary to treat the endometriosis.

The patient signed a consent form that included BSO. The patient did not indicate that she did not understand the language on the form; had she asked, an interpreter would have been provided.

VERDICT A $750,000 New York settlement was reached with the gynecologist and medical center.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Is there a link between impaired mobility and urinary incontinence in elderly, community-dwelling women?

Urinary incontinence affects more than one-third of women aged 70 years or older. As the authors of this study point out, urinary incontinence is comparable to other chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, in its impact on quality of life, and is a common reason for institutionalization.

The risk of urinary incontinence increases with age. In elderly women, it is often mixed (ie, having both urge- and stress-related components) and associated with functional impairments, including reduced mobility. It is thought that the association between incontinence and functional impairment is related primarily to the urge component:

- Women with impaired mobility take longer to reach the toilet, increasing the risk of leakage when the urge to urinate is strong

- Women with urge incontinence may be more likely to limit their activities so that they are always near a toilet.

Cognitive impairment may also play a role, affecting motor skills and bladder control.

To better understand why advancing age is linked with urinary incontinence, Fritel and colleagues studied a population of 1,942 urban-dwelling French women aged 75 to 85 years (mean age, 79.3 years; mean body mass index, 25.9 kg/m2).

Details of the study

Investigators assessed the frequency and quantity of urine leaks, the impact of urinary incontinence on daily life, and the participants’ mobility and balance. Data on urinary incontinence were collected via a self-administered questionnaire (the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form). Motor-related physical function was assessed using standardized balance and gait tests.

Urinary incontinence was reported by 42% of participants. Of these women, 57% reported daily urine leakage, with mixed incontinence found to be more prevalent than urge incontinence, which was more prevalent than stress incontinence. Overall, women with urinary incontinence reported that its impact on daily life was mild. Among those with mixed or urge incontinence, limitations in mobility and balance were correlated significantly with the severity of incontinence.

What this evidence means for practice

These findings support earlier data suggesting that impaired mobility can promote urge and mixed urinary incontinence. Because there also is a possibility that cerebral deterioration in aging women causes gait and balance problems that increase the likelihood of urge incontinence, the authors advise against the use of anticholinergic agents in elderly women, as these drugs can impair cognitive function. Another take-home message from this French report is that we should counsel elderly patients about the importance of maintaining balance and mobility through exercise, physical therapy, or other strategies.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Urinary incontinence affects more than one-third of women aged 70 years or older. As the authors of this study point out, urinary incontinence is comparable to other chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, in its impact on quality of life, and is a common reason for institutionalization.

The risk of urinary incontinence increases with age. In elderly women, it is often mixed (ie, having both urge- and stress-related components) and associated with functional impairments, including reduced mobility. It is thought that the association between incontinence and functional impairment is related primarily to the urge component:

- Women with impaired mobility take longer to reach the toilet, increasing the risk of leakage when the urge to urinate is strong

- Women with urge incontinence may be more likely to limit their activities so that they are always near a toilet.

Cognitive impairment may also play a role, affecting motor skills and bladder control.

To better understand why advancing age is linked with urinary incontinence, Fritel and colleagues studied a population of 1,942 urban-dwelling French women aged 75 to 85 years (mean age, 79.3 years; mean body mass index, 25.9 kg/m2).

Details of the study

Investigators assessed the frequency and quantity of urine leaks, the impact of urinary incontinence on daily life, and the participants’ mobility and balance. Data on urinary incontinence were collected via a self-administered questionnaire (the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form). Motor-related physical function was assessed using standardized balance and gait tests.

Urinary incontinence was reported by 42% of participants. Of these women, 57% reported daily urine leakage, with mixed incontinence found to be more prevalent than urge incontinence, which was more prevalent than stress incontinence. Overall, women with urinary incontinence reported that its impact on daily life was mild. Among those with mixed or urge incontinence, limitations in mobility and balance were correlated significantly with the severity of incontinence.

What this evidence means for practice

These findings support earlier data suggesting that impaired mobility can promote urge and mixed urinary incontinence. Because there also is a possibility that cerebral deterioration in aging women causes gait and balance problems that increase the likelihood of urge incontinence, the authors advise against the use of anticholinergic agents in elderly women, as these drugs can impair cognitive function. Another take-home message from this French report is that we should counsel elderly patients about the importance of maintaining balance and mobility through exercise, physical therapy, or other strategies.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Urinary incontinence affects more than one-third of women aged 70 years or older. As the authors of this study point out, urinary incontinence is comparable to other chronic conditions, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, in its impact on quality of life, and is a common reason for institutionalization.

The risk of urinary incontinence increases with age. In elderly women, it is often mixed (ie, having both urge- and stress-related components) and associated with functional impairments, including reduced mobility. It is thought that the association between incontinence and functional impairment is related primarily to the urge component:

- Women with impaired mobility take longer to reach the toilet, increasing the risk of leakage when the urge to urinate is strong

- Women with urge incontinence may be more likely to limit their activities so that they are always near a toilet.

Cognitive impairment may also play a role, affecting motor skills and bladder control.

To better understand why advancing age is linked with urinary incontinence, Fritel and colleagues studied a population of 1,942 urban-dwelling French women aged 75 to 85 years (mean age, 79.3 years; mean body mass index, 25.9 kg/m2).

Details of the study

Investigators assessed the frequency and quantity of urine leaks, the impact of urinary incontinence on daily life, and the participants’ mobility and balance. Data on urinary incontinence were collected via a self-administered questionnaire (the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Short Form). Motor-related physical function was assessed using standardized balance and gait tests.

Urinary incontinence was reported by 42% of participants. Of these women, 57% reported daily urine leakage, with mixed incontinence found to be more prevalent than urge incontinence, which was more prevalent than stress incontinence. Overall, women with urinary incontinence reported that its impact on daily life was mild. Among those with mixed or urge incontinence, limitations in mobility and balance were correlated significantly with the severity of incontinence.

What this evidence means for practice

These findings support earlier data suggesting that impaired mobility can promote urge and mixed urinary incontinence. Because there also is a possibility that cerebral deterioration in aging women causes gait and balance problems that increase the likelihood of urge incontinence, the authors advise against the use of anticholinergic agents in elderly women, as these drugs can impair cognitive function. Another take-home message from this French report is that we should counsel elderly patients about the importance of maintaining balance and mobility through exercise, physical therapy, or other strategies.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Imperforate hymen in your adolescent patient: Don’t miss the diagnosis

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

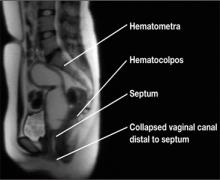

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

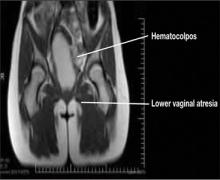

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

Many gynecologists encounter imperforate hymen, a congenital vaginal anomaly, in general practice. As such, it is important to have a basic understanding of the condition and to be aware of appropriate screening, evaluation, and management. This knowledge will allow you to differentiate imperforate hymen from more complex anomalies—preventing significant morbidity that could result from performing the wrong surgical procedure on this condition—and to provide optimal surgical management.

How often and why does it occur?

Imperforate hymen occurs in approximately 1/1000 newborn girls. It is the most common obstructive anomaly of the female reproductive tract.1,2

The hymen consists of fibrous connective tissue attached to the vaginal wall. In the perinatal period, the hymen serves to separate the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus (UGS); this is usually perforated during embryonic life by canalization of the most caudal portion of the vaginal plate at the UGS. This establishes a connection between the lumen of the vaginal canal and the vaginal vestibule.3 Failure of the hymen to perforate completely in the perinatal period can result in varying anomalies, including imperforate (FIGURE 1), microperforate, cribiform, or septated hymen.

Figure 1. Imperforate hymen

How does it present?

Its presentation is variable and frequently asymptomatic in infants and children.4 As a result, the diagnosis is often delayed until puberty.3

In infancy. Newborns typically will present with a hymenal bulge from hydrocolpos or mucocolpos, which result from maternal estrogen secretion on the newborn’s vaginal epithelium.5 This is usually asymptomatic and self limited.

Rarely, large hydrocolpos/mucocolpos may become symptomatic and can lead to urinary obstruction, or they can present as an abdominal mass or intestinal obstruction.4

In adolescence. The majority of adolescents will present with cyclic or persistent pelvic pain and primary amenorrhea. If significant hematometra is present, an abdominal mass also may be palpated. In extreme cases, the patient may present with mass effect symptoms, including back pain, pain with defecation, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, or hydronephrosis.6 Retrograde passage of blood into the fallopian tubes can cause hematosalpinx, which can lead to endometriosis and adhesion formation. Blood also may pass freely into the peritoneal cavity, forming hemoperitoneum.3

Related article: Your age-based guide to comprehensive well-woman care

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (October 2012)

Imperforate hymen, vaginal septum, or distal vaginal atresia?

When in doubt, refer. Imperforate hymen can be confused with distal vaginal atresia or low transverse vaginal septum. Often, the patient may present with similar signs and symptoms in all 3 cases. Accurately differentiating imperforate hymen from the former two more complex congenital anomalies prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity. As such, it is important to appropriately define the anatomy and refer the complex cases to a specialist comfortable and skilled in managing congenital anomalies, usually a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist or reproductive endocrinologist.

Imperforate hymen

Examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.7 This finding, coupled with a rectal examination and pelvic ultrasonography is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.6,8 However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis should be obtained in cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or the physical exam is more consistent with vaginal septum or agenesis.

Transverse vaginal septum

A reverse septum results from failure of the müllerian duct derivatives and UGS to fuse or canalize. This can occur in the lower, middle, or upper portion of the vagina, and septa may be thick or thin.6 Low transverse septa are more easily confused with imperforate hymen. Examination usually reveals a normal hymen with a short vagina posteriorly. In cases of extreme hematocolpos, vaginal septa also may present with a perineal bulge but, again, this will be posterior to a normal hymen.

Distal vaginal atresia

This condition occurs during embryonic development when the UGS fails to contribute to the lower portion of the vagina (FIGURE 2).5 In cases of distal vaginal atresia there is a lack of vaginal orifice, or only a vaginal dimple may be present.5,6 Rectovaginal examination will reveal a palpable mass if the upper vagina is distended with blood.6

Figure 2. Lower vaginal atresia

MRI is vital to firm diagnosis

In addition to pelvic ultrasonography, pelvic MRI is necessary to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum (FIGURE 3) and lower vaginal atresia (FIGURE 4), as preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of a vaginal septum as well as measurement of the total length of agenesis is imperative.6-8 Misdiagnosis of the vaginal septa or atresia as an imperforate hymen can lead to significant scarring and stenosis and can make corrective surgical procedures difficult or suboptimal.

| Figure 3. MRI of transverse vaginal septum |

Figure 4. MRI of lower vaginal atresia

Surgical management: hymenectomy

Imperforate hymen is managed surgically with hymenectomy. Repair is generally reserved for the newborn period or, ideally, in adolescence, as at puberty the presence of estrogen aids in surgical repair and healing.5 Simple aspiration of hematocolpos/ mucocolpos can lead to ascending infection, and pyocolpos and should be avoided.6

The goal of hymenectomy is to:

-

open the hymeneal membrane to allow egress of fluid and menstrual flow

-

allow for tampon use

The procedure is relatively straightforward and usually is performed under general anesthesia, although regional anesthesia also is an option.

Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions

Cruciate incision

1. Incise the hymen at the 2-, 4-, 8-, and 10-o’clock positions into four quadrants.

2. Excise the quadrants along the lateral wall of the vagina.

Elliptical incision

1. Make a circumferential incision with the Bovie electrocautery, incising the hymenal membrane close to the hymenal ring.

U-incision

1. Similar to the elliptical incision, use the Bovie electrocautery to incise the tissue close to the hymenal ring posterior and laterally in a “u” shape.

2. Make a horizontal incision superiorly to remove the extra tissue.

Vertical incision

This incision has been described in cases where there is an attempt to spare the hymen for religious or cultural preference.

1. Make a midline vertical hymenotomy less than 1 cm. Drain the borders of the hymen.

2. Apply suture obliquely to form a circular opening.

References

1. Dominguez C, Rock J, Horowitz I. Surgical conditions of the vagina and urethra. In: TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1997.

2. Basaran M, Usal D, Aydemir C. Hymen sparing surgery for imperforate hymen: case reports and review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(4):e61–e64.

Tips to a successful procedure

Ensure adequate suctioning. Before starting the procedure, insert a Foley catheter to completely drain the bladder and delineate the urethra. Making an initial incision into the hymen usually results in the expulsion of the old blood and mucus, which can be very thick and viscous; therefore, it is important to have adequate suction tubing.

Prevent scarring. After evacuating the old blood and mucus, excise the hymeneal membrane with a cruciate incision as is traditionally described. Alternatively, some experts use an elliptical incision or u-incision. (See “Steps to the varying hymenectomy incisions”.) Prevent excision of the hymenal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis and dyspareunia.3

Suturing the mucosal margins is likely unnecessary in adolescent patients. After excision of the hymenal tissue, one option is to suture the mucosal margins of the hymenal ring in an interrupted fashion with a fine, delayed-absorbable suture. Alternatively, at our institution, where we employ the u-incision (FIGURE 5), we assure hemostasis of the mucosal margins and do not suture the margins. Suturing the margins is believed to prevent adherence of the edges; however, in the pubertal girl, adherence is unlikely secondary to estrogen exposure.

Figure 5. Surgical correction with u-incision

Avoid infection; do not irrigate. We do not recommend that you irrigate the vagina and perform unnecessary uterine manipulation, as this may introduce bacteria into the dilated cervix and uterus.3,8

Septate/microperforate/cribiform hymen

These other hymeneal anomalies also may require surgical correction if they become clinically significant. Patients may present with difficulty inserting or removing a tampon, insertional dyspareunia, or incomplete drainage of menstrual blood.6

Imaging is usually not indicated to diagnose these hymenal anomalies, as physical examination will reveal a patent vaginal tract. A moistened Q-tip can be placed into the orifice or behind the septate hymen for confirmation (FIGURE 6).

Surgical correction of a microperforate or cribiform hymen is performed using the same principles as imperforate hymen.

Surgical correction of a septate hymen involves tying and suturing or clamping with a hemostat the upper and lower edges, with the excess hymenal tissue between the sutures then excised.8

Figure 6. Septate hymen

Postop care and follow up

Postoperative analgesia with lidocaine jelly or ice packs is usually sufficient for pain management. Reinforce proper hygienic care measures. At 2- to 3-week follow up, assess the patient for healing and evaluate the size of the hymenal orifice.

Key takeaways

-Differentiating imperforate hymen from low transverse vaginal septum or distal vaginal agenesis prior to surgery is of utmost importance because management is very different, and performing the wrong procedure can result in serious morbidity.

-With imperforate hymen, examination of the external genitalia reveals a perineal bulge secondary to hematocolpos.

-Pelvic MRI is essential to delineate the anatomy with both vaginal septum and agenesis, for preoperative evaluation of location and thickness of septum as well as measurement of total length of agenesis.

-Hymenectomy is relatively straightforward and may be performed using a cruciate, elliptical, or u-incision.

-Care should be taken to prevent excision of hymeneal tissue too close to the vaginal mucosa, as this can lead to scarring and stenosis, and later lead to dyspareunia.

The Affordable Care Act and the drive for electronic health records: Are small practices being squeezed?

Two years ago, I zeroed in on the pressures straining small ObGyn practices in an article entitled, “Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?”1 The pressures haven’t eased in the interim. Today, small practices are still feeling squeezed to keep up with the many demands of modern specialty care. The push for electronic health records (EHRs), in particular, can profoundly affect physicians in private practice.

In this article, I outline some of the challenges facing small practices when they set out to implement EHRs, as well as the potential benefits they stand to gain a little farther down the road. Before we begin, however, let’s look at the latest trends in ObGyn practice, as they are related, in part, to the need to implement EHRs.

The exodus from private practice continues

A 2012 Accenture Physicians Alignment Survey shows an accelerating increase in physician employment. In 2000, 57% of all physicians were in independent practice; by the end of 2013, only 36% of physicians are projected to remain independent.2

The ObGyn specialty is a clear part of this trend, with both seasoned and incoming physicians finding hospital or other employment an attractive alternative to private practice. Fully one-third of ObGyn residents entering practice today sign hospital employment contracts. ObGyns who have made the switch from private to hospital practice, or who have become ObGyn hospitalists, often point to the difficulties of maintaining a solvent private practice, especially given the push toward EHRs and increasing regulatory and administrative burdens, as justification for their move.

The main reasons for the shift to employment. Top concerns influencing physicians’ decisions to opt for employment include:

- business expenses (87%)

- the dominance of managed care (61%)

- the requirement for EHRs (53%)

- the need to maintain and manage staff (53%)

- the increasing number of patients needed to break even (39%).2

A 2008 socioeconomic survey from ACOG revealed that 23.6% of ObGyn practices are solo practices, and 27.1% are single-specialty group practices. Many ObGyns—especially those in solo or small practices—are hesitant to make the large capital investment that is necessary to adopt EHRs.

EHRs offer benefits—and real costs

The system-wide benefits of health information technology (HIT), including EHRs, are many. Insurers stand to save money by reducing unnecessary tests, and patients will benefit from better coordination of their care and fewer medical errors. But these advantages don’t necessarily translate into savings or revenue for physician practices. Instead, physicians face payment cuts from Medicare and private insurance.

Although there’s wide agreement that HIT can improve quality of care and reduce health-care costs, fewer than one-quarter (22%) of office-based physicians had adopted EHRs by 2009. We know the main reasons why:

- upfront cost and maintenance expense

- uncertain return on investment

- fragmented business model in a high proportion of small and solo practices

- changing and inconsistent information technology (IT) systems.

What can a practice expect to fork over?

In 2011, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found that the “real-life” cost of implementing EHRs “in an average five-physician primary care practice, operating within a large physician network committed to network-wide implementation of electronic health records, is about $162,000, with an additional $85,500 in maintenance expenses during the first year.”3

These figures include an average of 134 hours needed per physician to prepare to use EHRs during patient visits.3

Fleming and colleagues investigated the cost associated with implementing EHRs within 26 primary care practices in Texas. They found the cost to be $32,409 per physician through the first 60 days after the EHR system was launched, with one-time costs for hardware of $25,000 per practice and an additional $7,000 per physician for personal computers, printers, and scanners. The annual cost of software and maintenance was approximately $17,100 per physician.4

Why physicians should hold out for the return on their investment

Despite these considerable expenses, EHRs hold promise over the long term. The Medical Group Management Association reported, through a 2009 survey of about 1,300 primary care and specialty practice members using EHRs, that efficiency gains from the elimination of paper charts, as well as transcription savings, better charge capturing, and reduced billing errors, resulted in a median revenue increase of $49,916 per full-time physician after operating costs.

After 5 years of EHR use, practices reported a median operating margin 10.1% higher than that of practices in the first year of EHR use.5

Trends in the adoption of EHRs

Private practice. An article in Health Affairs showed that, by 2011, only one in six office-based physicians was using an EHR system robust enough to approach “meaningful use”—that is, the use of EHRs to measurably improve the quality of health care.6 These robust systems offered physicians the ability to record information on patient demographics, view laboratory and imaging results, maintain patients’ problem lists, compile clinical notes, and manage prescription ordering. EHR adoption lagged among non−primary care physicians, physicians aged 55 and older, and physicians in small (1–2 providers) practices and physician-owned practices.6 (ObGyns were considered primary care providers in this survey.)

“Big” practice. By comparison, in 2011, 99% of physicians in health maintenance organizations, or HMOs, and 73% in academic health centers and other hospitals used EHR systems.6 The number of physicians in these practice settings is small but growing.

In 2011, only 17% of physicians were in large practices of 10 or more physicians; 40% were in practices of one or two physicians.6

Primary care. These practices lead others in the adoption of EHRs, in part because of federal assistance, including a nationwide system of regional HIT assistance centers established by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act to help providers located in rural areas participate in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) programs in EHR. The goal of these programs is to provide HIT support to at least 100,000 primary care providers, including ObGyns, by 2014.

The numbers cited in the Health Affairs article largely mirror data developed by other research organizations, including the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions.6

The EHR incentive

The drive for EHRs started long before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was passed in 2010. The US Congress took a first stab at encouraging the health-care community to embrace HIT in 1996, when it passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA created an electronic data interchange that health plans, health-care clearinghouses, and certain health-care providers, including pharmacists, are required to use for electronic transactions, including:

- claims and encounter information

- payment and remittance advice

- claims status

- eligibility

- enrollment and disenrollment

- referrals and authorizations

- coordination of benefits

- premium payment.

Congress stepped up its game in 2009, when it offered higher Medicare and Medicaid payments to physicians who adopt and “meaningfully use” EHRs. The HITECH Act included $30 billion in new Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments—as much as $44,000 under Medicare and $63,750 under Medicaid—as well as $500 million for states to develop health information exchanges.

The Act also established a government-led process for certification of electronic health records through a $35 billion appropriation for the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT, housed in CMS.

Other programs designed to encourage use of EHRs

Other federal programs include the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), which, when created in 2006, was a voluntary physician electronic reporting program. Under the ACA, however, it has become a mandate. Starting in 2015, Medicare payments will be reduced for nonparticipating physicians.

The Electronic Prescribing (eRx) Incentive Program, created in 2008 under the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act, provides incentives for eligible physicians who e-prescribe Medicare Part D medications through a qualified system. This program converted to a penalty program last year for physicians who don’t use eRx.

Grants were also provided under the HITECH Act to fund an HIT infrastructure and low-interest HIT loans. The AHRQ has awarded $300 million in federal grant money to more than 200 projects in 48 states to promote access to and encourage HIT adoption. Over $150 million in Medicaid transformation grants have been awarded to three states and territories for HIT in the Medicaid program under the 2005 Deficit Reduction Act.

The ACA carried these initiatives even further by establishing uniform standards that HIT systems must meet, including:

- automatic reconciliation of electronic fund transfers and HIPAA payment and remittance

- improved claims payment process

- consistent methods of health plan enrollment and claim edits

- simplified and improved routing of health-care transactions

- electronic claims attachments.

Clearly, a lot of effort and taxpayer dollars have been dedicated to drive efficient use of HIT and EHRs in the hopes that they can:

- help make sense of our increasingly fragmented health-care system

- improve patient safety

- increase efficiency

- reduce paperwork

- reduce unnecessary tests

- better coordinate patient care.

To see which providers are cashing in on the government’s incentives for EHRs, see “Some physicians are more likely to seek incentives for meaningful use of EHRs” on page 37.

The long view

HIT and EHRs are here to stay. Products are maturing and improving. Acceptance by large and small practices has gained traction. Are small practices being squeezed? No doubt.

In 2011, I urged all ObGyns—especially those in private practice—to read an article written by President Barack Obama’s health-reform deputies on how physicians can be successful under the ACA.1 It reads, in part:

To realize the full benefits of the Affordable Care Act, physicians will need to embrace rather than resist change. The economic forces put in motion by the Act are likely to lead to vertical organization of providers and accelerate physician employment by hospitals and aggregation into larger physician groups. The most successful physicians will be those who most effectively collaborate with other providers to improve outcomes, care productivity, and patient experience.7

1. DiVenere L, Yates J. Is private ObGyn practice on its way out? OBG Manage. 2011;23(10):42–54.

2. More US doctors leaving private practice due to rising costs and technology mandates, Accenture report finds [news release]. Arlington, Virginia: Accenture Newsroom; October 31, 2012. http://newsroom.accenture.com/news/more-us-doctors-leaving-private-practice-due-to-rising-costs-and-technology-mandates-accenture-report-finds.htm. Accessed June 5, 2013.

3. Study identifies costs of implementing electronic health records in network of physician practices: Research Activities October 2011, No. 374. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. http://www.ahrq.gov/news/newsletters/research-activities/oct11/1011RA15.html. Accessed June 5, 2013.