User login

Intermittent pain and stiffness

The history and findings in this case are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis.

Psoriatic spondylitis is a form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) that affects the spine and the joints in the pelvis (axial involvement). PsA is a chronic, heterogeneous condition that affects approximately 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis, particularly those with severe psoriasis or nail or scalp involvement. It is characterized by musculoskeletal inflammation (arthritis, enthesitis, spondylitis, and dactylitis). PsA is a spondyloarthritis that can be found either in the peripheral or axial skeleton. If not treated, it may result in permanent joint damage and loss of function.

Patients with PsA may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Common symptoms of axial involvement in PsA include morning back/neck stiffness that lasts longer than 30 minutes, neck or back pain that improves with activity and worsens after prolonged inactivity, and diminished mobility. PsA affects men and women equally, and typically develops when patients are between 30 and 50 years of age. As with psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

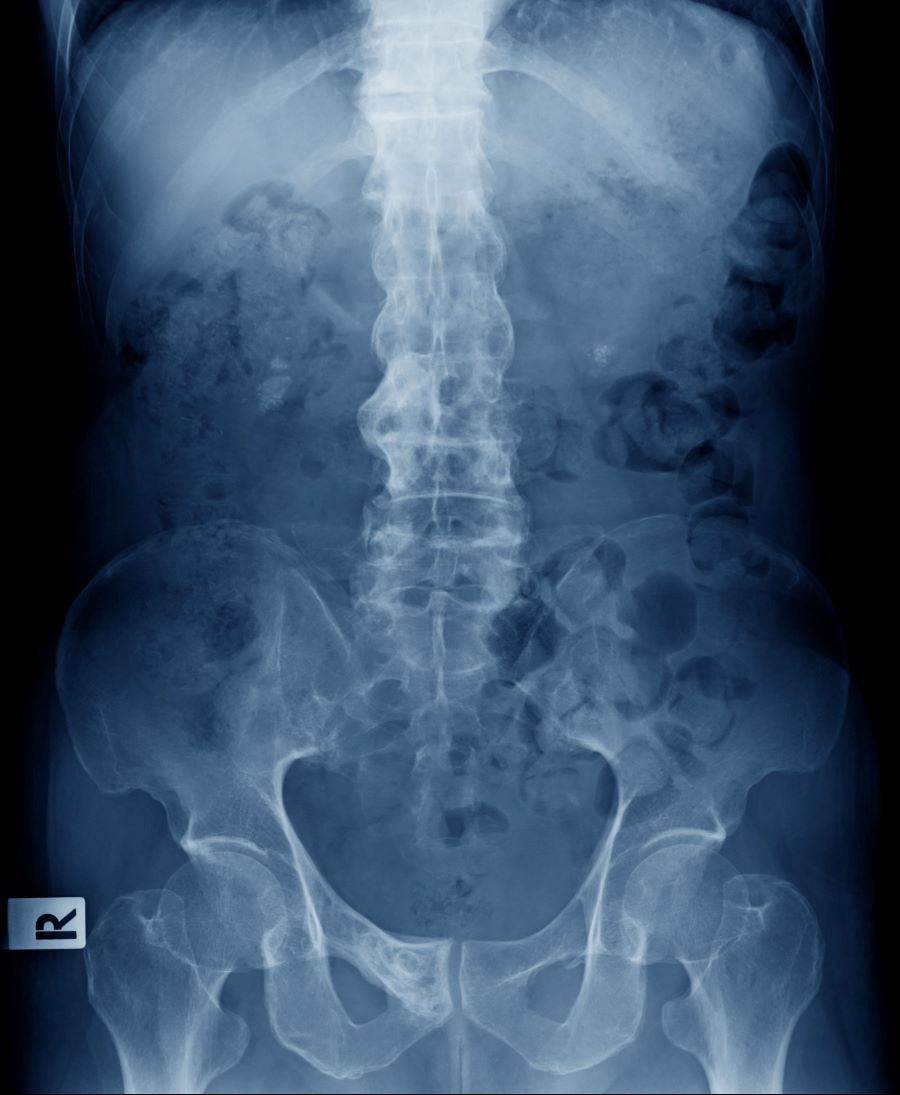

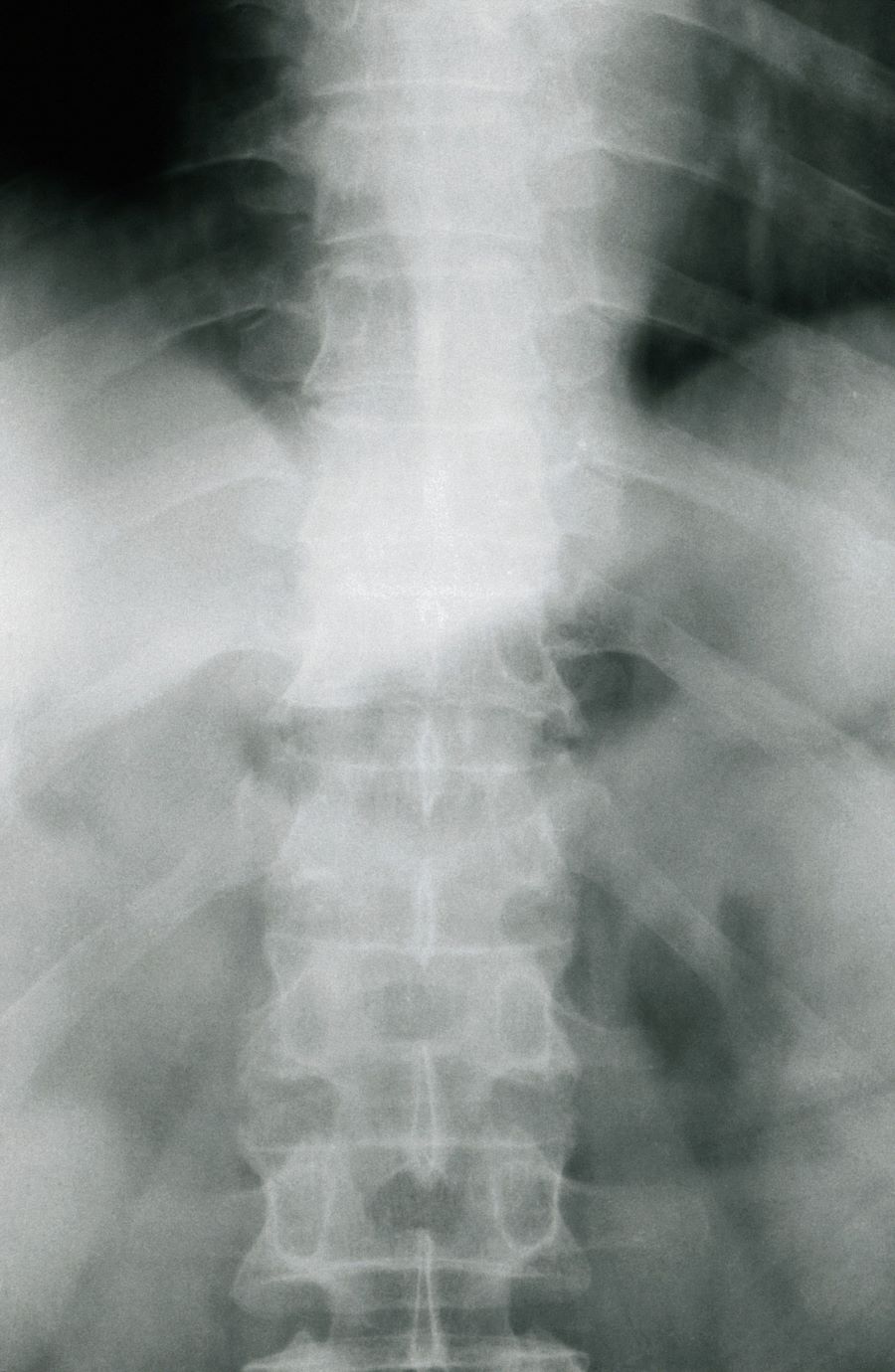

The diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosus). Useful imaging tools for evaluating patients with PsA include plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI. Although MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography for detecting early joint inflammation and damage and axial changes, including sacroiliitis, they are not mandatory for a diagnosis of PsA to be made.

International guidelines have been developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society to guide the treatment of axial PsA. The goals of treatment include minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; improving functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Treatment options for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or have erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity, guidelines recommend initiation of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (eg, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (eg, methotrexate) are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective. In patients with significant skin involvement, treatment with interleukin-17A inhibitors may be preferred to TNF inhibitors.

If patients have an inadequate response to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, guidelines recommend trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic. For patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered. Additionally, nonpharmacologic therapies (eg, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis.

Psoriatic spondylitis is a form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) that affects the spine and the joints in the pelvis (axial involvement). PsA is a chronic, heterogeneous condition that affects approximately 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis, particularly those with severe psoriasis or nail or scalp involvement. It is characterized by musculoskeletal inflammation (arthritis, enthesitis, spondylitis, and dactylitis). PsA is a spondyloarthritis that can be found either in the peripheral or axial skeleton. If not treated, it may result in permanent joint damage and loss of function.

Patients with PsA may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Common symptoms of axial involvement in PsA include morning back/neck stiffness that lasts longer than 30 minutes, neck or back pain that improves with activity and worsens after prolonged inactivity, and diminished mobility. PsA affects men and women equally, and typically develops when patients are between 30 and 50 years of age. As with psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

The diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosus). Useful imaging tools for evaluating patients with PsA include plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI. Although MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography for detecting early joint inflammation and damage and axial changes, including sacroiliitis, they are not mandatory for a diagnosis of PsA to be made.

International guidelines have been developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society to guide the treatment of axial PsA. The goals of treatment include minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; improving functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Treatment options for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or have erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity, guidelines recommend initiation of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (eg, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (eg, methotrexate) are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective. In patients with significant skin involvement, treatment with interleukin-17A inhibitors may be preferred to TNF inhibitors.

If patients have an inadequate response to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, guidelines recommend trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic. For patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered. Additionally, nonpharmacologic therapies (eg, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are consistent with a diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis.

Psoriatic spondylitis is a form of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) that affects the spine and the joints in the pelvis (axial involvement). PsA is a chronic, heterogeneous condition that affects approximately 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis, particularly those with severe psoriasis or nail or scalp involvement. It is characterized by musculoskeletal inflammation (arthritis, enthesitis, spondylitis, and dactylitis). PsA is a spondyloarthritis that can be found either in the peripheral or axial skeleton. If not treated, it may result in permanent joint damage and loss of function.

Patients with PsA may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Common symptoms of axial involvement in PsA include morning back/neck stiffness that lasts longer than 30 minutes, neck or back pain that improves with activity and worsens after prolonged inactivity, and diminished mobility. PsA affects men and women equally, and typically develops when patients are between 30 and 50 years of age. As with psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

The diagnosis of psoriatic spondylitis is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosus). Useful imaging tools for evaluating patients with PsA include plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI. Although MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography for detecting early joint inflammation and damage and axial changes, including sacroiliitis, they are not mandatory for a diagnosis of PsA to be made.

International guidelines have been developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR), and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society to guide the treatment of axial PsA. The goals of treatment include minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; improving functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Treatment options for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or have erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity, guidelines recommend initiation of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (eg, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (eg, methotrexate) are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective. In patients with significant skin involvement, treatment with interleukin-17A inhibitors may be preferred to TNF inhibitors.

If patients have an inadequate response to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, guidelines recommend trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic. For patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered. Additionally, nonpharmacologic therapies (eg, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 41-year-old man with a 5-year history of moderate to severe scalp psoriasis presents with complaints of intermittent pain and stiffness in his left hip and lower back of approximately 6 months' duration. The patient states that his back pain has been severe enough to wake him up on several occasions. Treatment with over-the-counter ibuprofen is moderately effective at relieving his pain. He also reports morning back stiffness that improves with motion, usually within an hour of awakening. The patient reports no fever, pain, swelling, or worsening of his scalp psoriasis. He is not aware of any injury or other triggering factor for his back pain. He takes an over-the-counter multivitamin daily and treats his scalp psoriasis with fluocinolone acetonide 0.01% oil. The patient is 5 ft 9 in and weighs 176 lb (BMI 26).

Physical examination reveals tenderness in the lumbar spine and associated decreased range of motion, as well as psoriatic plaques on the scalp. Vital signs are within normal ranges. Pertinent laboratory findings include erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 19 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 10 mg/L. Rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody were negative. Radiographic findings include sacroiliitis and bulky nonmarginal syndesmophytes.

Skin changes and pain

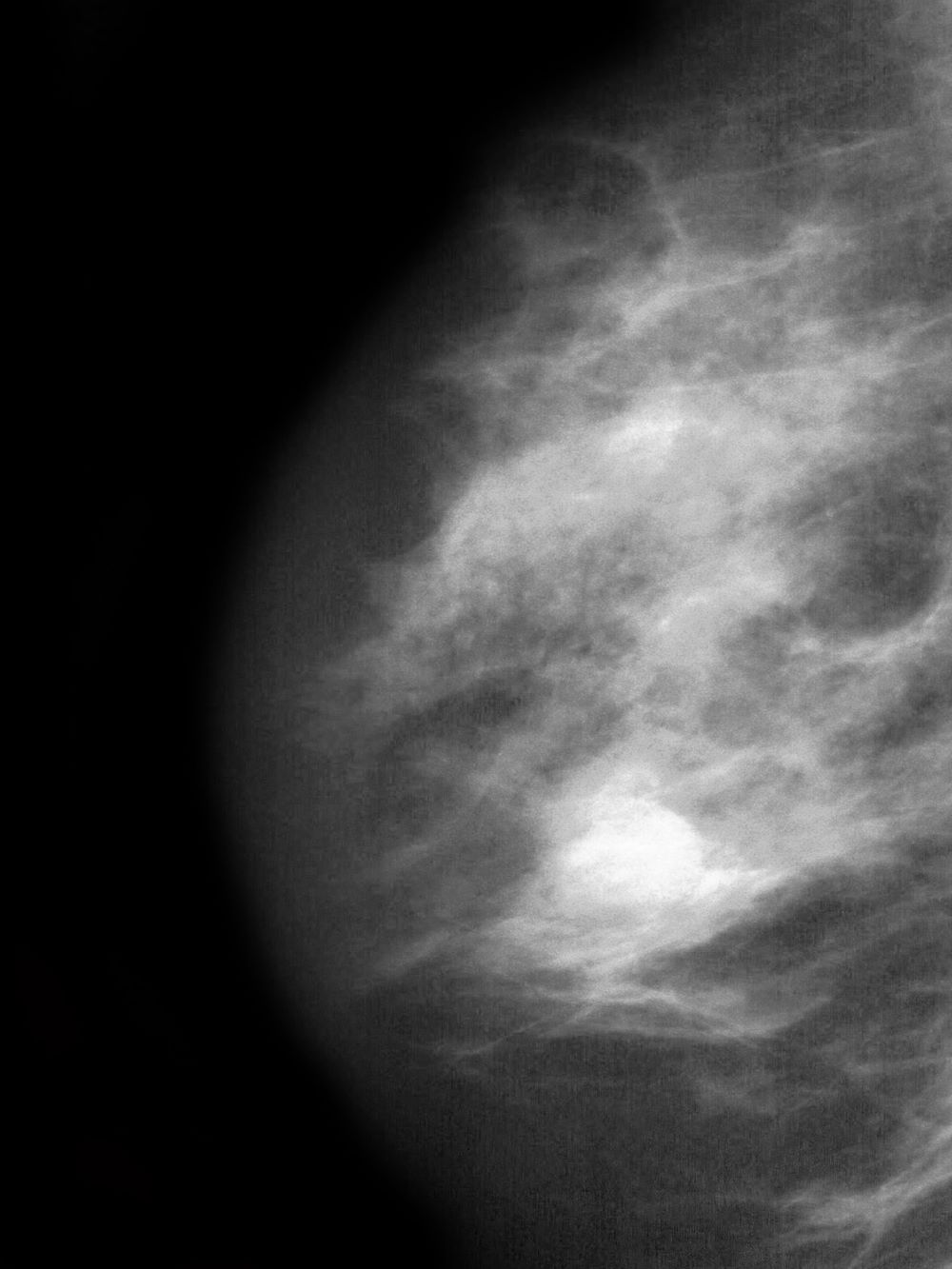

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of inflammatory breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the leading life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, estimates suggest that 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Inflammatory breast cancer is a rare and highly aggressive subtype of locally advanced breast cancer. In the United States, inflammatory breast cancer accounts for approximately 2%-4% of breast cancer cases. Although its incidence is rare, 7% of breast cancer caused mortality is attributed to inflammatory breast cancer. Cases of inflammatory breast cancer tend to be diagnosed at a younger age compared with noninflammatory breast cancer cases. Risk factors include African-American race and obesity.

The symptoms of inflammatory breast cancer can vary broadly, ranging from subtle skin erythema to diffuse breast involvement with skin dimpling and nipple inversion. Diagnostic criteria include erythema occupying at least one third of the breast, edema, peau d'orange, and/or warmth, with or without an underlying mass; rapid onset (< 3 months); and pathologic confirmation of invasive breast carcinoma. Histologic findings include florid tumor emboli that obstruct dermal lymphatics, which results in swelling and inflammation of the affected breast.

Inflammatory breast cancer has been associated with a poor prognosis. However, treatment advances are helping to improve outcomes. Currently, 5-year survival rates are reported to be 40%-70%, with a median survival of 2-4 years. According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the first-line treatment of inflammatory breast cancer involves neoadjuvant chemotherapy, modified radical mastectomy, and adjuvant radiation to the chest wall and regional nodes. Endocrine treatment should also be given to patients who are ER-positive and/or PR-positive (sequential chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy). For patients who are HER2-positive, up to 1 year of HER2-targeted therapy should be given. HER2-targeted therapies can be administered concurrently with radiation and with endocrine therapy if indicated.

Delayed reconstruction after mastectomy remains the clinical standard for inflammatory breast cancer. This is because the need to resect involved skin negates the benefit of skin-sparing mastectomy for immediate reconstruction. Moreover, high rates of local and distant recurrence warrant comprehensive regional node irradiation in a timely fashion, which may be more challenging or subject to delay after immediate reconstruction. Rarely, the extent of skin excision at the time of mastectomy prohibits primary or local closure. In such cases, reconstruction of the chest wall defect with autologous tissue is required, and concomitant immediate reconstruction may be undertaken.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of inflammatory breast cancer, in the first line and beyond, are available from the NCCN.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of inflammatory breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the leading life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, estimates suggest that 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Inflammatory breast cancer is a rare and highly aggressive subtype of locally advanced breast cancer. In the United States, inflammatory breast cancer accounts for approximately 2%-4% of breast cancer cases. Although its incidence is rare, 7% of breast cancer caused mortality is attributed to inflammatory breast cancer. Cases of inflammatory breast cancer tend to be diagnosed at a younger age compared with noninflammatory breast cancer cases. Risk factors include African-American race and obesity.

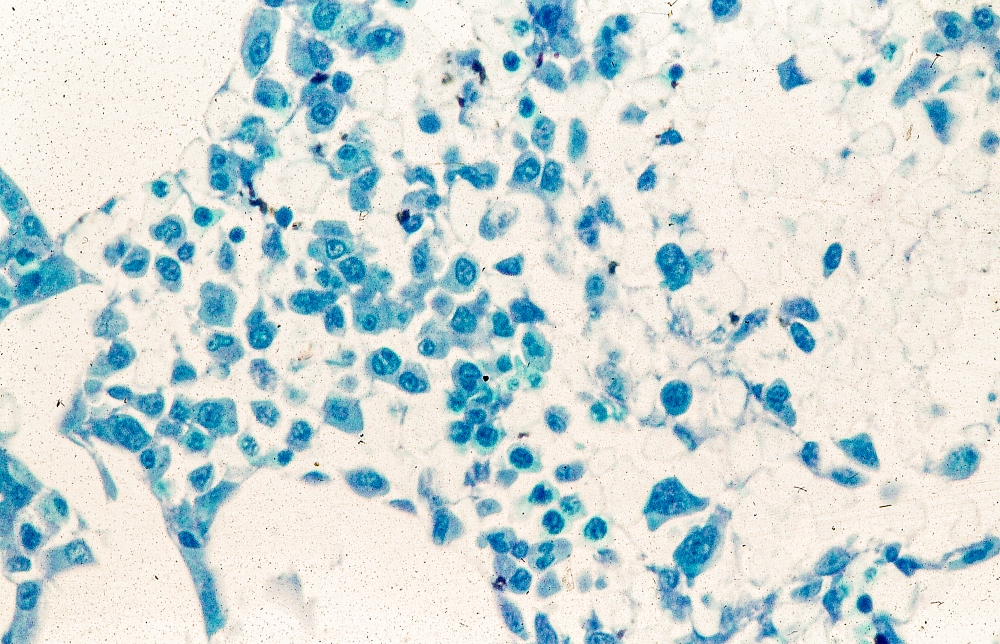

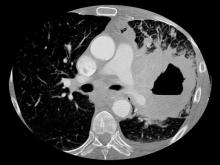

The symptoms of inflammatory breast cancer can vary broadly, ranging from subtle skin erythema to diffuse breast involvement with skin dimpling and nipple inversion. Diagnostic criteria include erythema occupying at least one third of the breast, edema, peau d'orange, and/or warmth, with or without an underlying mass; rapid onset (< 3 months); and pathologic confirmation of invasive breast carcinoma. Histologic findings include florid tumor emboli that obstruct dermal lymphatics, which results in swelling and inflammation of the affected breast.

Inflammatory breast cancer has been associated with a poor prognosis. However, treatment advances are helping to improve outcomes. Currently, 5-year survival rates are reported to be 40%-70%, with a median survival of 2-4 years. According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the first-line treatment of inflammatory breast cancer involves neoadjuvant chemotherapy, modified radical mastectomy, and adjuvant radiation to the chest wall and regional nodes. Endocrine treatment should also be given to patients who are ER-positive and/or PR-positive (sequential chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy). For patients who are HER2-positive, up to 1 year of HER2-targeted therapy should be given. HER2-targeted therapies can be administered concurrently with radiation and with endocrine therapy if indicated.

Delayed reconstruction after mastectomy remains the clinical standard for inflammatory breast cancer. This is because the need to resect involved skin negates the benefit of skin-sparing mastectomy for immediate reconstruction. Moreover, high rates of local and distant recurrence warrant comprehensive regional node irradiation in a timely fashion, which may be more challenging or subject to delay after immediate reconstruction. Rarely, the extent of skin excision at the time of mastectomy prohibits primary or local closure. In such cases, reconstruction of the chest wall defect with autologous tissue is required, and concomitant immediate reconstruction may be undertaken.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of inflammatory breast cancer, in the first line and beyond, are available from the NCCN.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of inflammatory breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the leading life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, estimates suggest that 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Inflammatory breast cancer is a rare and highly aggressive subtype of locally advanced breast cancer. In the United States, inflammatory breast cancer accounts for approximately 2%-4% of breast cancer cases. Although its incidence is rare, 7% of breast cancer caused mortality is attributed to inflammatory breast cancer. Cases of inflammatory breast cancer tend to be diagnosed at a younger age compared with noninflammatory breast cancer cases. Risk factors include African-American race and obesity.

The symptoms of inflammatory breast cancer can vary broadly, ranging from subtle skin erythema to diffuse breast involvement with skin dimpling and nipple inversion. Diagnostic criteria include erythema occupying at least one third of the breast, edema, peau d'orange, and/or warmth, with or without an underlying mass; rapid onset (< 3 months); and pathologic confirmation of invasive breast carcinoma. Histologic findings include florid tumor emboli that obstruct dermal lymphatics, which results in swelling and inflammation of the affected breast.

Inflammatory breast cancer has been associated with a poor prognosis. However, treatment advances are helping to improve outcomes. Currently, 5-year survival rates are reported to be 40%-70%, with a median survival of 2-4 years. According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the first-line treatment of inflammatory breast cancer involves neoadjuvant chemotherapy, modified radical mastectomy, and adjuvant radiation to the chest wall and regional nodes. Endocrine treatment should also be given to patients who are ER-positive and/or PR-positive (sequential chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy). For patients who are HER2-positive, up to 1 year of HER2-targeted therapy should be given. HER2-targeted therapies can be administered concurrently with radiation and with endocrine therapy if indicated.

Delayed reconstruction after mastectomy remains the clinical standard for inflammatory breast cancer. This is because the need to resect involved skin negates the benefit of skin-sparing mastectomy for immediate reconstruction. Moreover, high rates of local and distant recurrence warrant comprehensive regional node irradiation in a timely fashion, which may be more challenging or subject to delay after immediate reconstruction. Rarely, the extent of skin excision at the time of mastectomy prohibits primary or local closure. In such cases, reconstruction of the chest wall defect with autologous tissue is required, and concomitant immediate reconstruction may be undertaken.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of inflammatory breast cancer, in the first line and beyond, are available from the NCCN.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 51-year-old nonsmoking Black woman presents with a lump in her left breast, as well as associated skin changes and pain of approximately 3 months' duration. The patient last underwent routine screening breast imaging 2 years earlier. The patient is 5 ft 7 in and weighs 200 lb (BMI 31.3). Previous medical history is unremarkable. There is a family history of breast cancer (maternal aunt) and lung cancer (maternal uncle). Physical examination reveals a palpable abnormality in the left breast with edema, skin thickening, and peau d'orange. More than one third of the breast is erythematous. A bilateral mammography reveals an irregular mass and calcifications in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast as well as numerous additional masses and focal asymmetries involving the upper outer and lower outer quadrant of the left breast that extend into the inner left breast. A 1.6-cm mass in the upper left breast is noted, with total abnormality spanning 12.7 cm. Left axillary lymphadenopathy is also observed. Skin punch biopsy of the affected breast reveals dermal lymphatic invasion by tumor cells and tumor emboli. Left axial fine-needle aspiration biopsy reveals malignant cells.

Pruritus and swelling

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

CKD affects between 8% and 16% of the population worldwide. Risk factors for CKD are numerous and include T2D, hypertension, and prediabetes. Diabetes is the leading cause of CKD. Up to 40% of patients with diabetes develop diabetic kidney disease, which can progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. In fact, diabetic kidney disease is the top cause of ESRD in the United States.

Diagnostic criteria for CKD include elevated urinary albumin excretion (albuminuria) and/or eGFR < 60 mL/1.73 m2 that persists for more than 3 months. The normal presentation of diabetic kidney disease includes long-standing diabetes, retinopathy, albuminuria without gross hematuria, and gradually progressive decline of eGFR. However, signs of diabetic kidney disease may be present in patients at diagnosis or without retinopathy in T2D. Reduced eGFR without albuminuria has been frequently reported in both type 1 diabetes (T1D) and T2D and is becoming increasingly common as the prevalence of diabetes rises in the United States.

Chronic kidney disease is usually identified through routine screening with serum chemistry profile and urine studies or as an incidental finding. Less often, patients may present with symptoms, such as gross hematuria, "foamy urine" (a sign of albuminuria), nocturia, flank pain, or decreased urine output. In advanced cases, patients may report fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, a metallic taste, unintentional weight loss, pruritus, changes in mental status, dyspnea, and/or peripheral edema.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes describes five stages of CKD. Stages 1-2 are defined by evidence of high albuminuria with eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, while stages 3-5 are defined by progressively lower ranges of eGFR. Of note, at any eGFR, the degree of albuminuria is associated with risk for cardiovascular disease, CKD progression, and mortality. Thus, as noted by the ADA Standards, both eGFR and albuminuria should be used to guide treatment decisions; additionally, eGFR levels are essential for modifying drug dosages or restrictions of use, and the degree of albuminuria should influence selection of antihypertensive agents and glucose-lowering medications.

According to the ADA 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes, for people with non–dialysis-dependent CKD, dietary protein intake should be ∼0.8 g/kg body weight per day (the recommended daily allowance), as this level has been shown to slow GFR decline compared with higher levels of dietary protein intake, with evidence of a greater effect over time. Conversely, higher levels of dietary protein intake (> 20% of daily calories from protein or > 1.3 g/kg/d) have been associated with increased albuminuria, more rapid kidney function loss, and cardiovascular disease mortality. For patients on dialysis, higher levels of dietary protein intake should be considered, because malnutrition is a significant problem in some of these patients.

Urinary excretion of sodium and potassium may be impaired in patients with reduced eGFR. Thus, restriction of dietary sodium to < 2300 mg/d may help to control blood pressure and reduce cardiovascular risk, and restriction of dietary potassium may be necessary to control serum potassium concentration.

Intensive glycemic control with the goal of achieving near-normoglycemia has been shown to delay the onset and progression of albuminuria and reduced eGFR in patients with diabetes. Insulin alone was used to lower blood glucose in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study of T1D while a variety of agents were used in clinical trials of T2D, supporting the conclusion that glycemic control itself helps prevent CKD and its progression. However, the presence of CKD affects the risks and benefits of intensive glycemic control and several glucose-lowering medications. In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial of T2D, increased adverse effects of intensive glycemic control (hypoglycemia and mortality) were seen among patients with kidney disease at baseline. Moreover, it may take at least 2 years to see improved eGFR outcomes as an effect of intensive glycemic control. Therefore, in some patients with prevalent CKD and substantial comorbidity, target A1c levels may be less intensive.

According to guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration, eGFR should be monitored while taking metformin and metformin is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Clinicians should assess the benefits and risks of continuing treatment when eGFR falls to < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The ADA recommends that sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors be given to all patients with stage 3 CKD or higher and T2D, regardless of glycemic control, as they have been shown to delay CKD progression and reduce heart failure risk independent of glycemic control. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) also have direct effects on the kidney and have been reported to improve renal outcomes compared with placebo. In patients for whom cardiovascular risk is a predominant problem, the ADA suggests using GLP-1 RAs for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Comprehensive guidance on the management of CKD in patients with T2D is available in the ADA 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

CKD affects between 8% and 16% of the population worldwide. Risk factors for CKD are numerous and include T2D, hypertension, and prediabetes. Diabetes is the leading cause of CKD. Up to 40% of patients with diabetes develop diabetic kidney disease, which can progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. In fact, diabetic kidney disease is the top cause of ESRD in the United States.

Diagnostic criteria for CKD include elevated urinary albumin excretion (albuminuria) and/or eGFR < 60 mL/1.73 m2 that persists for more than 3 months. The normal presentation of diabetic kidney disease includes long-standing diabetes, retinopathy, albuminuria without gross hematuria, and gradually progressive decline of eGFR. However, signs of diabetic kidney disease may be present in patients at diagnosis or without retinopathy in T2D. Reduced eGFR without albuminuria has been frequently reported in both type 1 diabetes (T1D) and T2D and is becoming increasingly common as the prevalence of diabetes rises in the United States.

Chronic kidney disease is usually identified through routine screening with serum chemistry profile and urine studies or as an incidental finding. Less often, patients may present with symptoms, such as gross hematuria, "foamy urine" (a sign of albuminuria), nocturia, flank pain, or decreased urine output. In advanced cases, patients may report fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, a metallic taste, unintentional weight loss, pruritus, changes in mental status, dyspnea, and/or peripheral edema.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes describes five stages of CKD. Stages 1-2 are defined by evidence of high albuminuria with eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, while stages 3-5 are defined by progressively lower ranges of eGFR. Of note, at any eGFR, the degree of albuminuria is associated with risk for cardiovascular disease, CKD progression, and mortality. Thus, as noted by the ADA Standards, both eGFR and albuminuria should be used to guide treatment decisions; additionally, eGFR levels are essential for modifying drug dosages or restrictions of use, and the degree of albuminuria should influence selection of antihypertensive agents and glucose-lowering medications.

According to the ADA 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes, for people with non–dialysis-dependent CKD, dietary protein intake should be ∼0.8 g/kg body weight per day (the recommended daily allowance), as this level has been shown to slow GFR decline compared with higher levels of dietary protein intake, with evidence of a greater effect over time. Conversely, higher levels of dietary protein intake (> 20% of daily calories from protein or > 1.3 g/kg/d) have been associated with increased albuminuria, more rapid kidney function loss, and cardiovascular disease mortality. For patients on dialysis, higher levels of dietary protein intake should be considered, because malnutrition is a significant problem in some of these patients.

Urinary excretion of sodium and potassium may be impaired in patients with reduced eGFR. Thus, restriction of dietary sodium to < 2300 mg/d may help to control blood pressure and reduce cardiovascular risk, and restriction of dietary potassium may be necessary to control serum potassium concentration.

Intensive glycemic control with the goal of achieving near-normoglycemia has been shown to delay the onset and progression of albuminuria and reduced eGFR in patients with diabetes. Insulin alone was used to lower blood glucose in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study of T1D while a variety of agents were used in clinical trials of T2D, supporting the conclusion that glycemic control itself helps prevent CKD and its progression. However, the presence of CKD affects the risks and benefits of intensive glycemic control and several glucose-lowering medications. In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial of T2D, increased adverse effects of intensive glycemic control (hypoglycemia and mortality) were seen among patients with kidney disease at baseline. Moreover, it may take at least 2 years to see improved eGFR outcomes as an effect of intensive glycemic control. Therefore, in some patients with prevalent CKD and substantial comorbidity, target A1c levels may be less intensive.

According to guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration, eGFR should be monitored while taking metformin and metformin is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Clinicians should assess the benefits and risks of continuing treatment when eGFR falls to < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The ADA recommends that sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors be given to all patients with stage 3 CKD or higher and T2D, regardless of glycemic control, as they have been shown to delay CKD progression and reduce heart failure risk independent of glycemic control. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) also have direct effects on the kidney and have been reported to improve renal outcomes compared with placebo. In patients for whom cardiovascular risk is a predominant problem, the ADA suggests using GLP-1 RAs for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Comprehensive guidance on the management of CKD in patients with T2D is available in the ADA 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

CKD affects between 8% and 16% of the population worldwide. Risk factors for CKD are numerous and include T2D, hypertension, and prediabetes. Diabetes is the leading cause of CKD. Up to 40% of patients with diabetes develop diabetic kidney disease, which can progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation. In fact, diabetic kidney disease is the top cause of ESRD in the United States.

Diagnostic criteria for CKD include elevated urinary albumin excretion (albuminuria) and/or eGFR < 60 mL/1.73 m2 that persists for more than 3 months. The normal presentation of diabetic kidney disease includes long-standing diabetes, retinopathy, albuminuria without gross hematuria, and gradually progressive decline of eGFR. However, signs of diabetic kidney disease may be present in patients at diagnosis or without retinopathy in T2D. Reduced eGFR without albuminuria has been frequently reported in both type 1 diabetes (T1D) and T2D and is becoming increasingly common as the prevalence of diabetes rises in the United States.

Chronic kidney disease is usually identified through routine screening with serum chemistry profile and urine studies or as an incidental finding. Less often, patients may present with symptoms, such as gross hematuria, "foamy urine" (a sign of albuminuria), nocturia, flank pain, or decreased urine output. In advanced cases, patients may report fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, a metallic taste, unintentional weight loss, pruritus, changes in mental status, dyspnea, and/or peripheral edema.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes describes five stages of CKD. Stages 1-2 are defined by evidence of high albuminuria with eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, while stages 3-5 are defined by progressively lower ranges of eGFR. Of note, at any eGFR, the degree of albuminuria is associated with risk for cardiovascular disease, CKD progression, and mortality. Thus, as noted by the ADA Standards, both eGFR and albuminuria should be used to guide treatment decisions; additionally, eGFR levels are essential for modifying drug dosages or restrictions of use, and the degree of albuminuria should influence selection of antihypertensive agents and glucose-lowering medications.

According to the ADA 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes, for people with non–dialysis-dependent CKD, dietary protein intake should be ∼0.8 g/kg body weight per day (the recommended daily allowance), as this level has been shown to slow GFR decline compared with higher levels of dietary protein intake, with evidence of a greater effect over time. Conversely, higher levels of dietary protein intake (> 20% of daily calories from protein or > 1.3 g/kg/d) have been associated with increased albuminuria, more rapid kidney function loss, and cardiovascular disease mortality. For patients on dialysis, higher levels of dietary protein intake should be considered, because malnutrition is a significant problem in some of these patients.

Urinary excretion of sodium and potassium may be impaired in patients with reduced eGFR. Thus, restriction of dietary sodium to < 2300 mg/d may help to control blood pressure and reduce cardiovascular risk, and restriction of dietary potassium may be necessary to control serum potassium concentration.

Intensive glycemic control with the goal of achieving near-normoglycemia has been shown to delay the onset and progression of albuminuria and reduced eGFR in patients with diabetes. Insulin alone was used to lower blood glucose in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study of T1D while a variety of agents were used in clinical trials of T2D, supporting the conclusion that glycemic control itself helps prevent CKD and its progression. However, the presence of CKD affects the risks and benefits of intensive glycemic control and several glucose-lowering medications. In the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial of T2D, increased adverse effects of intensive glycemic control (hypoglycemia and mortality) were seen among patients with kidney disease at baseline. Moreover, it may take at least 2 years to see improved eGFR outcomes as an effect of intensive glycemic control. Therefore, in some patients with prevalent CKD and substantial comorbidity, target A1c levels may be less intensive.

According to guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration, eGFR should be monitored while taking metformin and metformin is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Clinicians should assess the benefits and risks of continuing treatment when eGFR falls to < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The ADA recommends that sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors be given to all patients with stage 3 CKD or higher and T2D, regardless of glycemic control, as they have been shown to delay CKD progression and reduce heart failure risk independent of glycemic control. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) also have direct effects on the kidney and have been reported to improve renal outcomes compared with placebo. In patients for whom cardiovascular risk is a predominant problem, the ADA suggests using GLP-1 RAs for cardiovascular risk reduction.

Comprehensive guidance on the management of CKD in patients with T2D is available in the ADA 2023 Standards of Care in Diabetes.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 56-year-old Hispanic man presents and reports a 2-month history of fatigue, loss of appetite, pruritus, and swelling of the legs, ankles, and feet. The patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, and hyperlipidemia 7 years ago after an ophthalmologist diagnosed him with diabetic retinopathy and referred him for medical care. Since then, he has been inconsistent with attending regular follow-up visits. He is a current smoker (40-pack/year history).

At today's visit, the patient's blood pressure is 150/95 mm Hg, heart rate is 97 beats/min, and respiration rate is 29 breaths/min. He is 5 ft 9 in and weighs 210 lb (BMI 31). Current medications include metformin ER 1000 mg/d, atorvastatin 40 mg/d, amlodipine 10 mg/d, and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d. At a routine visit 4 months ago, the patient's estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 59 mL/min/1.73 m2; at a subsequent follow-up visit, his eGFR was 57 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Pertinent laboratory findings today include eGFR 56 mL/min/1.73 m2, serum creatinine 2.7 g/dL, serum albumin 3.3 g/dL, A1c 8.8%, glucose 189 mg/dL, and an albumin-creatinine ratio of 225 mg/g. All other findings are within normal ranges.

Worsening cognitive impairments

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

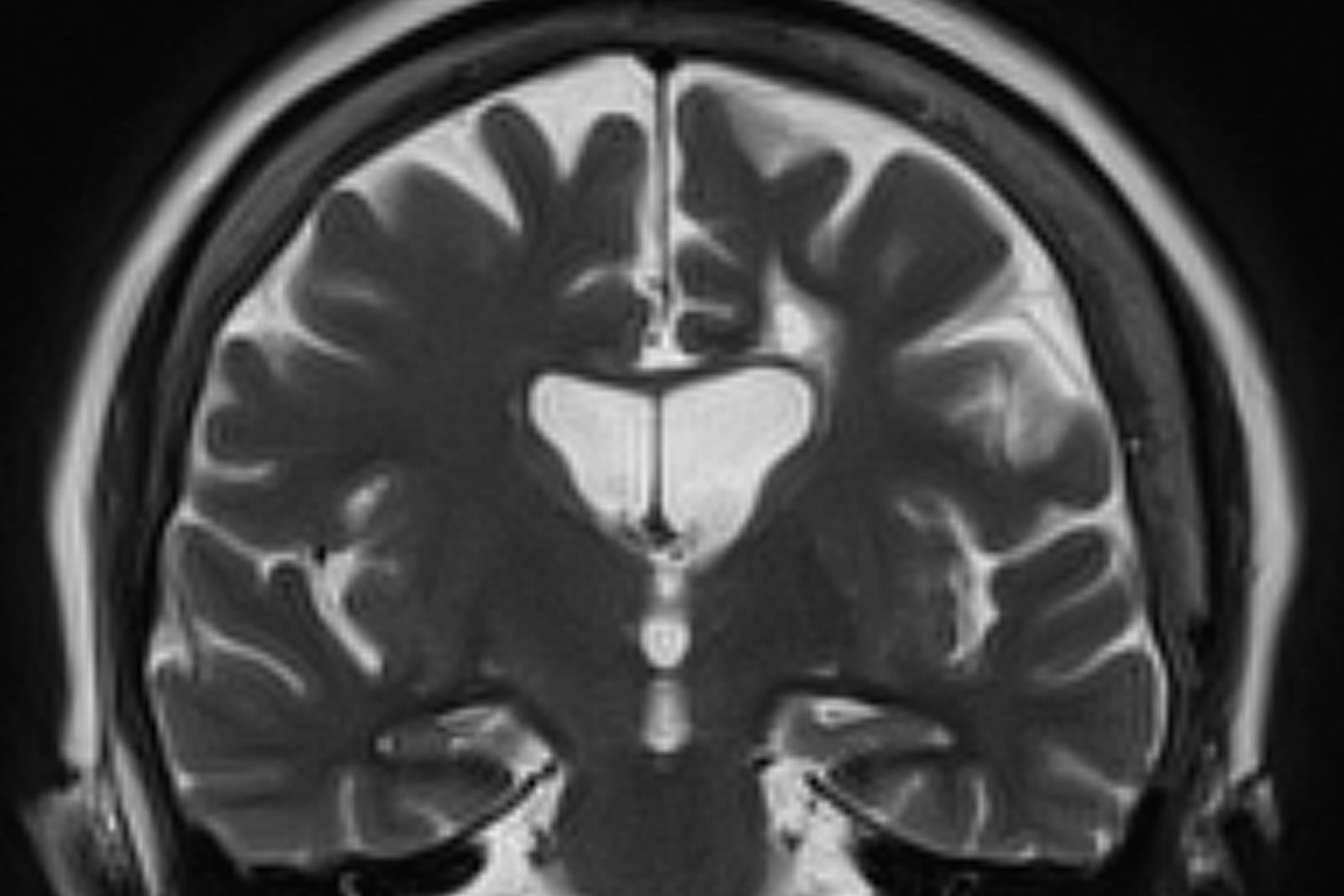

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

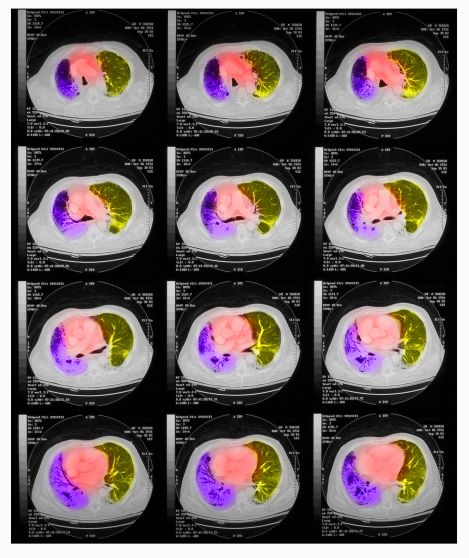

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 73-year-old male restaurant manager presents with concerns of progressively worsening cognitive impairment. The patient's symptoms began approximately 2 years ago. At that time, he attributed them to normal aging. Recently, however, he has begun to have increasing difficulties at work. On several occasions, he has forgotten to place important supply orders and has made errors with staff scheduling. His wife reports that he frequently misplaces items at home, such as his cell phone and car keys, and has been experiencing noticeable deficits with his short-term memory. In addition, he has been "unlike himself" for quite some time, with uncharacteristic episodes of depression, anxiety, and emotional lability. The patient's past medical history is significant for mild obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. There is no history of neurotoxic exposure, head injuries, strokes, or seizures. His family history is negative for dementia. Current medications include rosuvastatin 40 mg/d and metoprolol 100 mg/d. His current height and weight are 5 ft 11 in and 223 lb (BMI 31.1).

No abnormalities are noted on physical exam; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are within normal ranges, except for elevated levels of fasting blood glucose level (119 mg/dL) and A1c (6.3%). The patient scores 19 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. His clinician orders MRI scanning, which reveals generalized atrophy of brain tissue and an accentuated loss of tissue involving the temporal lobes.

Moderate to severe back pain

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Psoriasis is a complex, chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease that is associated with significant morbidity, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality. Approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States have psoriasis; worldwide, approximately 2%-3% of the population is affected. Patients with psoriasis frequently have comorbidities; PsA, an inflammatory, seronegative musculoskeletal disease, is among the most common. It is estimated that 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis develop PsA.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease. Patients may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Men and women are equally affected by PsA, which typically develops when patients are age 30-50 years. Like psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

PsA is a potentially erosive disease. Structural damage and functional impairment occurs within 2 years of initial assessment in approximately 50% of patients; as the disease progresses, patients may experience irreversible joint damage and disability. Axial involvement occurs in 25%-70% of patients with PsA; exclusive axial involvement is uncommon, occurring in 5% of patients. Common symptoms of axial PsA include inflammatory back pain (eg, pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest, morning stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes). Some patients with axial involvement may be asymptomatic. If untreated, cervical spinal mobility and lateral flexion significantly decline within 5 years in patients with axial PsA. In addition, sacroiliitis worsens over time; 37% and 52% of patients develop grade 2 or higher sacroiliitis within 5 and 10 years, respectively. This highlights the importance of early identification and treatment of patients with axial PsA.

The diagnosis of axial PsA is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosis). PsA can be differentiated from ankylosing spondylitis by the asymmetric and frequently unilateral presentation of sacroiliitis and syndesmophytes, which frequently presents as nonmarginal, bulky, asymmetric, and discontinuous skipping vertebral levels.

Plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI are all useful tools for evaluating patients with PsA. MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography is for detecting early joint inflammation and damage as well as axial changes, including sacroiliitis; however, they are not required for a diagnosis of PsA.

The treatment of axial PsA is based on international guidelines developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society–European League Against Rheumatism. Treatment focuses on minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; enhancing functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Medications for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; however, long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or if erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity is observed, guidelines recommend initiation of a TNF inhibitor. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective.

If symptoms of axial PsA are not controlled by NSAIDs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are recommended. However, interleukin 17A inhibitors may be used in preference to TNF inhibitors in patients with significant skin involvement. In the United States, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, and infliximab are recommended over etanercept for patients with axial SpA in the presence of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or recurrent uveitis (although there is no evidence for golimumab) because etanercept has contradictory results for uveitis and has not been shown to have efficacy in IBD.

If patients fail to respond to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic is recommended by US guidelines. A Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered for patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors.

Nonpharmacologic therapies (ie, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Psoriasis is a complex, chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease that is associated with significant morbidity, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality. Approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States have psoriasis; worldwide, approximately 2%-3% of the population is affected. Patients with psoriasis frequently have comorbidities; PsA, an inflammatory, seronegative musculoskeletal disease, is among the most common. It is estimated that 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis develop PsA.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease. Patients may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Men and women are equally affected by PsA, which typically develops when patients are age 30-50 years. Like psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

PsA is a potentially erosive disease. Structural damage and functional impairment occurs within 2 years of initial assessment in approximately 50% of patients; as the disease progresses, patients may experience irreversible joint damage and disability. Axial involvement occurs in 25%-70% of patients with PsA; exclusive axial involvement is uncommon, occurring in 5% of patients. Common symptoms of axial PsA include inflammatory back pain (eg, pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest, morning stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes). Some patients with axial involvement may be asymptomatic. If untreated, cervical spinal mobility and lateral flexion significantly decline within 5 years in patients with axial PsA. In addition, sacroiliitis worsens over time; 37% and 52% of patients develop grade 2 or higher sacroiliitis within 5 and 10 years, respectively. This highlights the importance of early identification and treatment of patients with axial PsA.

The diagnosis of axial PsA is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosis). PsA can be differentiated from ankylosing spondylitis by the asymmetric and frequently unilateral presentation of sacroiliitis and syndesmophytes, which frequently presents as nonmarginal, bulky, asymmetric, and discontinuous skipping vertebral levels.

Plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI are all useful tools for evaluating patients with PsA. MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography is for detecting early joint inflammation and damage as well as axial changes, including sacroiliitis; however, they are not required for a diagnosis of PsA.

The treatment of axial PsA is based on international guidelines developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society–European League Against Rheumatism. Treatment focuses on minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; enhancing functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Medications for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; however, long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or if erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity is observed, guidelines recommend initiation of a TNF inhibitor. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective.

If symptoms of axial PsA are not controlled by NSAIDs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are recommended. However, interleukin 17A inhibitors may be used in preference to TNF inhibitors in patients with significant skin involvement. In the United States, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, and infliximab are recommended over etanercept for patients with axial SpA in the presence of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or recurrent uveitis (although there is no evidence for golimumab) because etanercept has contradictory results for uveitis and has not been shown to have efficacy in IBD.

If patients fail to respond to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic is recommended by US guidelines. A Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered for patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors.

Nonpharmacologic therapies (ie, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of axial psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Psoriasis is a complex, chronic, inflammatory, immune-mediated disease that is associated with significant morbidity, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality. Approximately 7.4 million adults in the United States have psoriasis; worldwide, approximately 2%-3% of the population is affected. Patients with psoriasis frequently have comorbidities; PsA, an inflammatory, seronegative musculoskeletal disease, is among the most common. It is estimated that 25%-30% of patients with psoriasis develop PsA.

PsA is a heterogeneous disease. Patients may present with nail and skin changes, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), either alone or in combination. Men and women are equally affected by PsA, which typically develops when patients are age 30-50 years. Like psoriasis, PsA is associated with numerous comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression, uveitis, and anxiety.

PsA is a potentially erosive disease. Structural damage and functional impairment occurs within 2 years of initial assessment in approximately 50% of patients; as the disease progresses, patients may experience irreversible joint damage and disability. Axial involvement occurs in 25%-70% of patients with PsA; exclusive axial involvement is uncommon, occurring in 5% of patients. Common symptoms of axial PsA include inflammatory back pain (eg, pain that improves with activity but worsens with rest, morning stiffness lasting longer than 30 minutes). Some patients with axial involvement may be asymptomatic. If untreated, cervical spinal mobility and lateral flexion significantly decline within 5 years in patients with axial PsA. In addition, sacroiliitis worsens over time; 37% and 52% of patients develop grade 2 or higher sacroiliitis within 5 and 10 years, respectively. This highlights the importance of early identification and treatment of patients with axial PsA.

The diagnosis of axial PsA is confirmed by physical examination and imaging. Axial PsA characteristics, including sacroiliitis and spondylitis, are distinguished by the development of syndesmophytes (ie, ossification of the annulus fibrosis). PsA can be differentiated from ankylosing spondylitis by the asymmetric and frequently unilateral presentation of sacroiliitis and syndesmophytes, which frequently presents as nonmarginal, bulky, asymmetric, and discontinuous skipping vertebral levels.

Plain radiography, CT, ultrasound, and MRI are all useful tools for evaluating patients with PsA. MRI and ultrasound may be more sensitive than plain radiography is for detecting early joint inflammation and damage as well as axial changes, including sacroiliitis; however, they are not required for a diagnosis of PsA.

The treatment of axial PsA is based on international guidelines developed by the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society–European League Against Rheumatism. Treatment focuses on minimizing pain, stiffness, and fatigue; improving and preserving spinal flexibility and posture; enhancing functional capacity; and maintaining the ability to work, with a target of remission or minimal/low disease activity.

Medications for symptomatic relief include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and sacroiliac joint injections with glucocorticoids for mild disease; however, long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is not recommended. If patients remain symptomatic or if erosive disease or other indications of high disease activity is observed, guidelines recommend initiation of a TNF inhibitor. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, are not routinely prescribed for patients with axial disease because they have not been shown to be effective.

If symptoms of axial PsA are not controlled by NSAIDs, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are recommended. However, interleukin 17A inhibitors may be used in preference to TNF inhibitors in patients with significant skin involvement. In the United States, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, and infliximab are recommended over etanercept for patients with axial SpA in the presence of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or recurrent uveitis (although there is no evidence for golimumab) because etanercept has contradictory results for uveitis and has not been shown to have efficacy in IBD.

If patients fail to respond to a first trial of a TNF inhibitor, trying a second TNF inhibitor before switching to a different class of biologic is recommended by US guidelines. A Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib) may be considered for patients who do not respond to TNF inhibitors.

Nonpharmacologic therapies (ie, exercise, physical therapy, massage therapy, occupational therapy, acupuncture) are recommended for all patients with active PsA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.