User login

Woman presents with cough and bronchorrhea

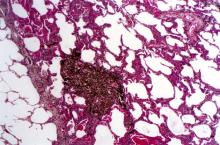

Bronchioalveolar cell carcinoma (BAC) is a variant of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that, in recent years, has received a new identity in some of the literature. Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) are relatively new entities that in some published literature have replaced the term BAC. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recognizes these terms. AIS is defined as a localized adenocarcinoma of < 3 cm that exhibits a lepidic growth pattern, with neoplastic cells along the alveolar structures but without stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion. MIA refers to small, solitary adenocarcinomas < 3 cm with either pure lepidic growth or predominant lepidic growth with ≤ 5 mm of stromal invasion. BAC has unique epidemiologic, pathologic, and clinical features compared with other NSCLC subtypes. For example, although it is smoking-related, the relationship of BAC to smoking is less strong than with other types of NSCLC. About a third of patients with BAC are never-smokers.

There are also some unique radiographic features — its presentation may be confused with pneumonia or other inflammatory conditions in the lung, and only after a patient does not improve after a course of antibiotics should a diagnosis of BAC be considered. Unlike other types of lung cancer where chemotherapy may be the first plan of attack, surgery is often the first choice for treating BAC, particularly when there is no mediastinal node involvement (10%-25% of cases) or distal metastases (5% of cases). BAC usually harbors EGFR mutation. It is responsive to new targeted therapies for lung cancer, particularly osimertinib, afatinib, erlotinib, and gefitinib. Thus, people with BAC are good candidates for genetic testing.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Bronchioalveolar cell carcinoma (BAC) is a variant of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that, in recent years, has received a new identity in some of the literature. Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) are relatively new entities that in some published literature have replaced the term BAC. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recognizes these terms. AIS is defined as a localized adenocarcinoma of < 3 cm that exhibits a lepidic growth pattern, with neoplastic cells along the alveolar structures but without stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion. MIA refers to small, solitary adenocarcinomas < 3 cm with either pure lepidic growth or predominant lepidic growth with ≤ 5 mm of stromal invasion. BAC has unique epidemiologic, pathologic, and clinical features compared with other NSCLC subtypes. For example, although it is smoking-related, the relationship of BAC to smoking is less strong than with other types of NSCLC. About a third of patients with BAC are never-smokers.

There are also some unique radiographic features — its presentation may be confused with pneumonia or other inflammatory conditions in the lung, and only after a patient does not improve after a course of antibiotics should a diagnosis of BAC be considered. Unlike other types of lung cancer where chemotherapy may be the first plan of attack, surgery is often the first choice for treating BAC, particularly when there is no mediastinal node involvement (10%-25% of cases) or distal metastases (5% of cases). BAC usually harbors EGFR mutation. It is responsive to new targeted therapies for lung cancer, particularly osimertinib, afatinib, erlotinib, and gefitinib. Thus, people with BAC are good candidates for genetic testing.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Bronchioalveolar cell carcinoma (BAC) is a variant of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that, in recent years, has received a new identity in some of the literature. Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) are relatively new entities that in some published literature have replaced the term BAC. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recognizes these terms. AIS is defined as a localized adenocarcinoma of < 3 cm that exhibits a lepidic growth pattern, with neoplastic cells along the alveolar structures but without stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion. MIA refers to small, solitary adenocarcinomas < 3 cm with either pure lepidic growth or predominant lepidic growth with ≤ 5 mm of stromal invasion. BAC has unique epidemiologic, pathologic, and clinical features compared with other NSCLC subtypes. For example, although it is smoking-related, the relationship of BAC to smoking is less strong than with other types of NSCLC. About a third of patients with BAC are never-smokers.

There are also some unique radiographic features — its presentation may be confused with pneumonia or other inflammatory conditions in the lung, and only after a patient does not improve after a course of antibiotics should a diagnosis of BAC be considered. Unlike other types of lung cancer where chemotherapy may be the first plan of attack, surgery is often the first choice for treating BAC, particularly when there is no mediastinal node involvement (10%-25% of cases) or distal metastases (5% of cases). BAC usually harbors EGFR mutation. It is responsive to new targeted therapies for lung cancer, particularly osimertinib, afatinib, erlotinib, and gefitinib. Thus, people with BAC are good candidates for genetic testing.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 50-year-old woman, a never-smoker, presented with complaints of intermittent cough and shortness of breath for 3 months, associated with bronchorrhea (copious watery sputum production). She had lost 15 pounds in the past 2 months and had dyspnea on exertion for 1 month. Her pulse rate was 88/min, respiratory rate 18/min, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. A chest x-ray (posteroanterior view) showed dense opacity in the right lower zone. Contrast-enhanced CT of the thorax showed diffuse ground-glass opacities around nodules and consolidation involving the apical and basal segments of the right lower lobe. Despite several courses of antimicrobials, bronchodilators, and IV corticosteroid therapy, the patient's condition worsened.

Reports of dysuria and nocturia

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

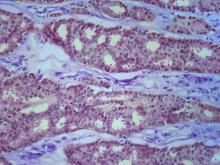

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

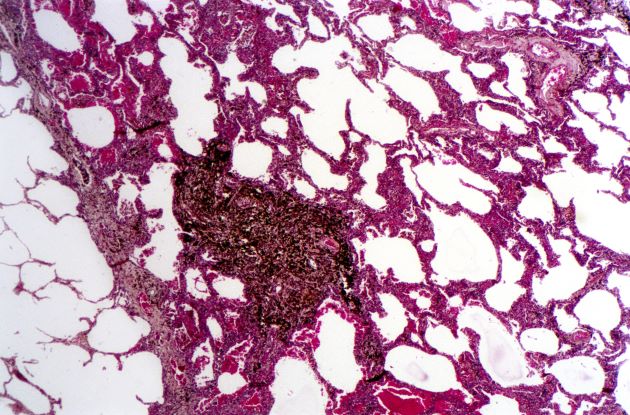

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 69-year-old nonsmoking African American man presents with reports of dysuria, nocturia, and unintentional weight loss. He reveals no other lower urinary tract symptoms, pelvic pain, night sweats, back pain, or excessive fatigue. Digital rectal exam reveals an enlarged prostate with a firm, irregular nodule at the right side of the gland. Laboratory tests reveal a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 2.22 ng/mL; a comprehensive metabolic panel and CBC are within normal limits. The patient is 6 ft 1 in and weighs 187 lb.

A transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy is performed. Histologic examination reveals immunoreactivity for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and expression of transcription factor 1. A proliferation of small cells (> 4 lymphocytes in diameter) is noted, with scant cytoplasm, poorly defined borders, finely granular salt-and-pepper chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and a high mitotic count. Evidence of perineural invasion is noted.

Depression and emotional lability

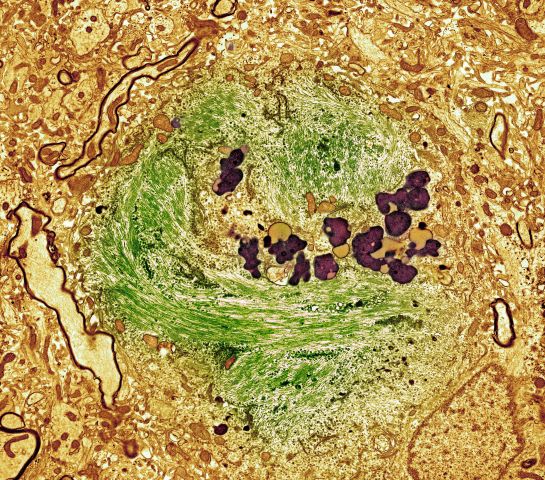

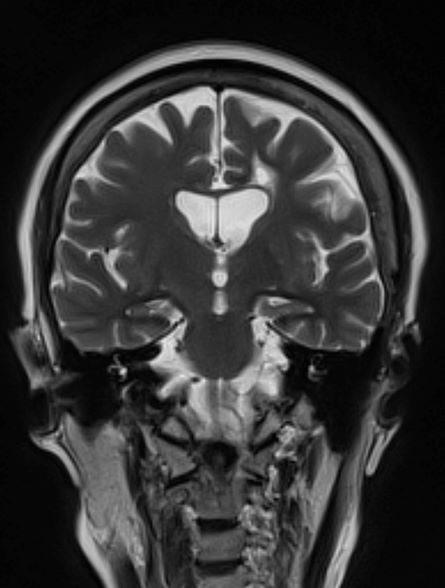

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 51-year-old man presents with complaints of progressively worsening cognitive impairments, particularly in executive functioning and episodic memory, as well as depression, apathy, and emotional lability. The patient is accompanied by his wife, who states that he often becomes irritable and "flies off the handle" without provocation. The patient's depressive symptoms began approximately 18 months ago, shortly after his mother's death from heart failure. Both he and his wife initially attributed his symptoms to the grieving process; however, in the past 6 months, his depression and mood swings have become increasingly frequent and intense. In addition, he was recently mandated to go on administrative leave from his job as an IT manager because of poor performance and angry outbursts in the workplace. The patient believes that his forgetfulness and difficulty regulating his emotions are the result of the depression he is experiencing. His goal today is to "get on some medication" to help him better manage his emotions and return to work. Although his wife is supportive of her husband, she is concerned about her husband's rapidly progressing deficits in short-term memory and is uncertain that they are related to his emotional symptoms.

The patient's medical history is notable for nine concussions sustained during his time as a high school and college football player; only one resulted in loss of consciousness. He does not currently take any medications. There is no history of tobacco use, illicit drug use, or excessive alcohol consumption. There is no family history of dementia. His current height and weight are 6 ft 3 in and 223 lb, and his BMI is 27.9.

No abnormalities are noted on physical exam; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are all within normal ranges, including thyroid-stimulating hormone and vitamin B12 levels. The patient scores 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, which is a set of 11 questions that doctors and other healthcare professionals commonly use to check for cognitive impairment. His clinician orders a brain MRI, which reveals a tau-positive neurofibrillary tangle in the neocortex.

Progressive back pain

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of advanced/metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed life-threatening cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, an estimated 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Tumor size, nodal spread, and distant metastases (TNM) at the time of diagnosis are key prognostic factors. Immunohistochemistry tumor markers (ie, estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], and HER2), as well as grade and Ki-67 expression, have also been shown to be independent predictors of breast cancer death and are used together with TNM to guide treatment decisions.

Despite advances in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, metastatic recurrence remains a significant problem. Although the incidence of distance relapse is declining and survival times for patients with recurrent disease are improving, 20%-30% of patients with early breast cancer still die of metastatic disease. Metastatic breast cancer recurrence can arise months to decades after initial diagnosis and treatment.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, biopsy is a critical component of the workup for patients with recurrent or stage IV disease. This is because biopsy ensures accurate determination of metastatic/recurrent disease and tumor histology and enables biomarker determination and selection of appropriate treatment. Soft-tissue tumor biopsy is preferred over bone sites unless a portion of the biopsy can be protected from harsh decalcification solution to preserve more accurate evaluation of biomarkers. Determination of HR status (ER and PR) and HER2 status should be repeated in all cases when diagnostic tissue is obtained because ER and PR assays may be falsely negative or falsely positive, and there may be discordance between the primary and metastatic tumors. According to the NCCN panel, re-testing the receptor status of recurrent disease should be performed, particularly when it was previously unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed.

Additionally, the staging evaluation of patients who present with recurrent or stage IV breast cancer should include history and physical exam; a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, chest diagnostic CT, bone scan, and radiography of any long or weight-bearing bones that are painful or appear abnormal on bone scan; diagnostic CT of the abdomen (with or without diagnostic CT of the pelvis) or MRI of the abdomen; and biopsy documentation of first recurrence whenever possible. The use of sodium fluoride PET or PET/CT for evaluating patients with recurrent disease is generally discouraged.

Presently, metastatic breast cancer remains incurable. However, in recent years, the treatment landscape for metastatic breast cancer has significantly advanced in all breast cancer subtypes, leading to improvements in progression-free survival and even overall survival in some cases. For example, newer, targeted approaches directly address mutation drivers and allow precise delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Detailed guidance on the treatment of breast cancer can be found here and in the full NCCN guidelines.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of advanced/metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed life-threatening cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, an estimated 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Tumor size, nodal spread, and distant metastases (TNM) at the time of diagnosis are key prognostic factors. Immunohistochemistry tumor markers (ie, estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], and HER2), as well as grade and Ki-67 expression, have also been shown to be independent predictors of breast cancer death and are used together with TNM to guide treatment decisions.

Despite advances in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, metastatic recurrence remains a significant problem. Although the incidence of distance relapse is declining and survival times for patients with recurrent disease are improving, 20%-30% of patients with early breast cancer still die of metastatic disease. Metastatic breast cancer recurrence can arise months to decades after initial diagnosis and treatment.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, biopsy is a critical component of the workup for patients with recurrent or stage IV disease. This is because biopsy ensures accurate determination of metastatic/recurrent disease and tumor histology and enables biomarker determination and selection of appropriate treatment. Soft-tissue tumor biopsy is preferred over bone sites unless a portion of the biopsy can be protected from harsh decalcification solution to preserve more accurate evaluation of biomarkers. Determination of HR status (ER and PR) and HER2 status should be repeated in all cases when diagnostic tissue is obtained because ER and PR assays may be falsely negative or falsely positive, and there may be discordance between the primary and metastatic tumors. According to the NCCN panel, re-testing the receptor status of recurrent disease should be performed, particularly when it was previously unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed.

Additionally, the staging evaluation of patients who present with recurrent or stage IV breast cancer should include history and physical exam; a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, chest diagnostic CT, bone scan, and radiography of any long or weight-bearing bones that are painful or appear abnormal on bone scan; diagnostic CT of the abdomen (with or without diagnostic CT of the pelvis) or MRI of the abdomen; and biopsy documentation of first recurrence whenever possible. The use of sodium fluoride PET or PET/CT for evaluating patients with recurrent disease is generally discouraged.

Presently, metastatic breast cancer remains incurable. However, in recent years, the treatment landscape for metastatic breast cancer has significantly advanced in all breast cancer subtypes, leading to improvements in progression-free survival and even overall survival in some cases. For example, newer, targeted approaches directly address mutation drivers and allow precise delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Detailed guidance on the treatment of breast cancer can be found here and in the full NCCN guidelines.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of advanced/metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed life-threatening cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, an estimated 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Tumor size, nodal spread, and distant metastases (TNM) at the time of diagnosis are key prognostic factors. Immunohistochemistry tumor markers (ie, estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], and HER2), as well as grade and Ki-67 expression, have also been shown to be independent predictors of breast cancer death and are used together with TNM to guide treatment decisions.

Despite advances in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, metastatic recurrence remains a significant problem. Although the incidence of distance relapse is declining and survival times for patients with recurrent disease are improving, 20%-30% of patients with early breast cancer still die of metastatic disease. Metastatic breast cancer recurrence can arise months to decades after initial diagnosis and treatment.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, biopsy is a critical component of the workup for patients with recurrent or stage IV disease. This is because biopsy ensures accurate determination of metastatic/recurrent disease and tumor histology and enables biomarker determination and selection of appropriate treatment. Soft-tissue tumor biopsy is preferred over bone sites unless a portion of the biopsy can be protected from harsh decalcification solution to preserve more accurate evaluation of biomarkers. Determination of HR status (ER and PR) and HER2 status should be repeated in all cases when diagnostic tissue is obtained because ER and PR assays may be falsely negative or falsely positive, and there may be discordance between the primary and metastatic tumors. According to the NCCN panel, re-testing the receptor status of recurrent disease should be performed, particularly when it was previously unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed.

Additionally, the staging evaluation of patients who present with recurrent or stage IV breast cancer should include history and physical exam; a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, chest diagnostic CT, bone scan, and radiography of any long or weight-bearing bones that are painful or appear abnormal on bone scan; diagnostic CT of the abdomen (with or without diagnostic CT of the pelvis) or MRI of the abdomen; and biopsy documentation of first recurrence whenever possible. The use of sodium fluoride PET or PET/CT for evaluating patients with recurrent disease is generally discouraged.

Presently, metastatic breast cancer remains incurable. However, in recent years, the treatment landscape for metastatic breast cancer has significantly advanced in all breast cancer subtypes, leading to improvements in progression-free survival and even overall survival in some cases. For example, newer, targeted approaches directly address mutation drivers and allow precise delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Detailed guidance on the treatment of breast cancer can be found here and in the full NCCN guidelines.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 62-year-old nonsmoking woman presents with progressive moderate to severe back pain. The patient has a history of endometriosis and node-positive invasive ductal breast cancer, which was diagnosed 15 years ago. The tumor was hormone receptor (HR)–positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative. After a lumpectomy, she received adjuvant chemotherapy, followed by radiation therapy and 5 years of adjuvant oral endocrine therapy. Physical examination reveals several large palpable nodes in the right axillary region; no abnormalities are noted in either breast or the left axillary region.

The patient is 5 ft 7 in and weighs 152 lb (BMI, 23.8). At her last visit, 3 years earlier, she weighed 176 lb. She states her weight loss has been unintentional and began about 6 months ago. The patient denies any respiratory or abdominal symptoms; she does report increasing fatigue, which she attributes to her back pain. Complete blood cell count values are within normal range, except for an elevated alkaline phosphatase level (215 IU/L).

A subsequent axillary lymph node ultrasound reveals several irregular hypoechoic masses in the right axilla of various sizes, the largest being 2.4 cm. PET, CT, and a bone scan were also performed and revealed multiple suspicious lesions in the spine and several pulmonary nodules.

History of nonproductive cough

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of eosinophilic asthma.

Asthma is a common, chronic, and heterogeneous respiratory disease, most often characterized by chronic airway inflammation. Affected individuals experience respiratory symptoms (ie, wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and cough) that may fluctuate over time and in intensity, as well as variable expiratory airflow limitation, which may become persistent. For many patients, asthma has a significant impact on quality of life. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people and caused 455,000 deaths. Currently, approximately 334 million people worldwide are believed to be affected by asthma.

Asthma frequently begins in childhood, but adult-onset asthma can occur and often presents as a nonatopic and eosinophilic condition. In fact, asthma is an umbrella diagnosis that encompasses several diseases with distinct mechanistic pathways (endotypes) and variable clinical presentations (phenotypes), all of which manifest with respiratory symptoms and are accompanied by variable airflow obstruction.

Broadly, asthma endotypes are categorized as type 2 (T2)-high or T2-low. Eosinophilic asthma falls under the T2-high endotype and comprises three phenotypes: atopic, late-onset, and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Late-onset T2-high asthma is characterized by prominent blood and sputum eosinophilia and is refractory to inhaled/oral corticosteroid treatment. Patients in this subgroup tend to be older and have more severe asthma with fixed airflow obstruction and more frequent exacerbations; patients may also have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, which usually precedes asthma development. High FeNO levels and normal or elevated serum total IgE levels are also often seen in this subgroup.

The late-onset eosinophilic asthma phenotype accounts for 20%-40% of severe asthma cases and is associated with rapid decline of respiratory functions. Thus, earlier escalation of therapy may be indicated in patients with this phenotype.

According to a 2022 report from the Global Initiative for Asthma, the possibility of refractory T2 asthma should be considered when any of the following is found in patients taking high-dose ICS or daily oral corticosteroids:

• Blood eosinophils ≥ 150/μL, and/or

• FeNO ≥ 20 ppb, and/or

• Sputum eosinophils ≥ 2%, and/or

• Asthma is clinically allergen driven

Biologic T2-targeted therapies are available as add-on therapies for patients with T2 airway inflammation and severe asthma despite taking at least a high-dose ICS-LABA, and who have eosinophilic or allergic biomarkers or need maintenance oral corticosteroids. Available options for eosinophilic asthma include anti-interleukin (IL)-5/anti-IL-5R therapies (benralizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab) and anti-IL-4R therapy (dupilumab).

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of eosinophilic asthma.

Asthma is a common, chronic, and heterogeneous respiratory disease, most often characterized by chronic airway inflammation. Affected individuals experience respiratory symptoms (ie, wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and cough) that may fluctuate over time and in intensity, as well as variable expiratory airflow limitation, which may become persistent. For many patients, asthma has a significant impact on quality of life. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people and caused 455,000 deaths. Currently, approximately 334 million people worldwide are believed to be affected by asthma.

Asthma frequently begins in childhood, but adult-onset asthma can occur and often presents as a nonatopic and eosinophilic condition. In fact, asthma is an umbrella diagnosis that encompasses several diseases with distinct mechanistic pathways (endotypes) and variable clinical presentations (phenotypes), all of which manifest with respiratory symptoms and are accompanied by variable airflow obstruction.

Broadly, asthma endotypes are categorized as type 2 (T2)-high or T2-low. Eosinophilic asthma falls under the T2-high endotype and comprises three phenotypes: atopic, late-onset, and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Late-onset T2-high asthma is characterized by prominent blood and sputum eosinophilia and is refractory to inhaled/oral corticosteroid treatment. Patients in this subgroup tend to be older and have more severe asthma with fixed airflow obstruction and more frequent exacerbations; patients may also have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, which usually precedes asthma development. High FeNO levels and normal or elevated serum total IgE levels are also often seen in this subgroup.

The late-onset eosinophilic asthma phenotype accounts for 20%-40% of severe asthma cases and is associated with rapid decline of respiratory functions. Thus, earlier escalation of therapy may be indicated in patients with this phenotype.

According to a 2022 report from the Global Initiative for Asthma, the possibility of refractory T2 asthma should be considered when any of the following is found in patients taking high-dose ICS or daily oral corticosteroids:

• Blood eosinophils ≥ 150/μL, and/or

• FeNO ≥ 20 ppb, and/or

• Sputum eosinophils ≥ 2%, and/or

• Asthma is clinically allergen driven

Biologic T2-targeted therapies are available as add-on therapies for patients with T2 airway inflammation and severe asthma despite taking at least a high-dose ICS-LABA, and who have eosinophilic or allergic biomarkers or need maintenance oral corticosteroids. Available options for eosinophilic asthma include anti-interleukin (IL)-5/anti-IL-5R therapies (benralizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab) and anti-IL-4R therapy (dupilumab).

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of eosinophilic asthma.

Asthma is a common, chronic, and heterogeneous respiratory disease, most often characterized by chronic airway inflammation. Affected individuals experience respiratory symptoms (ie, wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and cough) that may fluctuate over time and in intensity, as well as variable expiratory airflow limitation, which may become persistent. For many patients, asthma has a significant impact on quality of life. According to the World Health Organization, asthma affected an estimated 262 million people and caused 455,000 deaths. Currently, approximately 334 million people worldwide are believed to be affected by asthma.

Asthma frequently begins in childhood, but adult-onset asthma can occur and often presents as a nonatopic and eosinophilic condition. In fact, asthma is an umbrella diagnosis that encompasses several diseases with distinct mechanistic pathways (endotypes) and variable clinical presentations (phenotypes), all of which manifest with respiratory symptoms and are accompanied by variable airflow obstruction.

Broadly, asthma endotypes are categorized as type 2 (T2)-high or T2-low. Eosinophilic asthma falls under the T2-high endotype and comprises three phenotypes: atopic, late-onset, and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Late-onset T2-high asthma is characterized by prominent blood and sputum eosinophilia and is refractory to inhaled/oral corticosteroid treatment. Patients in this subgroup tend to be older and have more severe asthma with fixed airflow obstruction and more frequent exacerbations; patients may also have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, which usually precedes asthma development. High FeNO levels and normal or elevated serum total IgE levels are also often seen in this subgroup.

The late-onset eosinophilic asthma phenotype accounts for 20%-40% of severe asthma cases and is associated with rapid decline of respiratory functions. Thus, earlier escalation of therapy may be indicated in patients with this phenotype.

According to a 2022 report from the Global Initiative for Asthma, the possibility of refractory T2 asthma should be considered when any of the following is found in patients taking high-dose ICS or daily oral corticosteroids:

• Blood eosinophils ≥ 150/μL, and/or

• FeNO ≥ 20 ppb, and/or

• Sputum eosinophils ≥ 2%, and/or

• Asthma is clinically allergen driven

Biologic T2-targeted therapies are available as add-on therapies for patients with T2 airway inflammation and severe asthma despite taking at least a high-dose ICS-LABA, and who have eosinophilic or allergic biomarkers or need maintenance oral corticosteroids. Available options for eosinophilic asthma include anti-interleukin (IL)-5/anti-IL-5R therapies (benralizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab) and anti-IL-4R therapy (dupilumab).

Zab Mosenifar, MD, Medical Director, Women's Lung Institute; Executive Vice Chairman, Department of Medicine, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California.

Zab Mosenifar, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 42-year-old nonsmoking man presents with complaints of a 9-month history of wheezing, nonproductive cough, and exertional dyspnea. The patient reports nighttime awakenings from his symptoms three to five times per month. He was diagnosed with asthma by his primary care provider about 3 months after his symptoms began. On diagnosis, he was prescribed a short-acting beta-2 adrenergic agonist rescue inhaler and an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), twice daily. Because the patient remained symptomatic, his primary care provider stepped up his daily therapy to a combined ICS and long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist (LABA). At today's visit, the patient reports continued symptoms and use of his rescue inhaler at least twice per week. He has no other significant medical history aside from a history of mild atopic dermatitis. He is 5 ft 11 in and currently weighs 172 lb (BMI 24). He demonstrates proper inhaler technique and states that he is compliant with his therapy.

Physical examination reveals loud wheezing during inspiration and throughout expiration. The patient's heart rate is 110 beats/min; blood pressure is 130/70 mm Hg. Pulse oximetry is 93%. Spirometry reveals a forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) of 78% predicted. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is 56 ppb. Chest radiography is normal. High-resolution CT shows air trapping, mosaic lung attenuations, and bronchial wall thickening. IgE level is normal; sputum culture reveals 6% eosinophils.

Intermittent abdominal pain

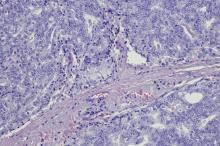

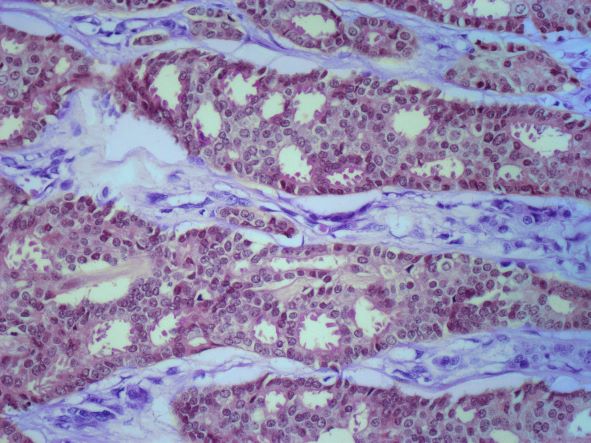

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by the proliferation of CD5-positive B cells within the mantle zone that surrounds normal germinal center follicles. MCL is a rare disease that most commonly presents in adult men (male to female ratio > 2:1) in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Individuals diagnosed with MCL typically present with constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, night sweats, persistent fever, and fatigue. Approximately 25% of cases present with extranodal involvement with the bone marrow; peripheral blood and gastrointestinal tract are most often involved. In patients with extensive node involvement in the gastrointestinal tract, additional symptoms at presentation often include abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and bloating. Skin involvement in MCL is rare and usually indicates widespread disease.

According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, a diagnosis of MCL is established on the basis of the morphologic examination findings and immunophenotyping.

Immunohistochemically, expression of cyclin D1 in normal lymphoid cells is very low and often undetectable; only hairy cell leukemia shows moderate expression of cyclin D1. Therefore, positive immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 is pathognomonic for MCL. Increased expression of cyclin D1 protein leads to dysregulation of the cell cycle and stimulates uncontrolled cell proliferation. It is also indirect evidence of the chromosomal translocation (11;14)(q13;q32) on the CCND1 gene, which is detected in 95% of cases of MCL. In addition, negative expression of antigens may also help to differentiate MCL from other lymphomas. MCL does not usually express the antigens that are associated with germinal centers, such as CD10, CD23, and BCL6. Thus, these antigens can be used to distinguish MCL from B-cell lymphomas of germinal center origin, including follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends chemotherapy followed by radiation for stage I or II disease. In general, patients with advanced-stage disease benefit from systemic chemotherapy. Because MCL is clinically heterogeneous, treatment may require adjustment on the basis of the patient's age, underlying comorbidities, and underlying MCL biology such as TP53 mutations. During induction therapy, prophylaxis and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome is strongly recommended to be considered. Before treatment, hepatitis B virus testing is recommended because of an increased risk for viral reactivation with use of immunotherapy regimens for treatment.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by the proliferation of CD5-positive B cells within the mantle zone that surrounds normal germinal center follicles. MCL is a rare disease that most commonly presents in adult men (male to female ratio > 2:1) in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Individuals diagnosed with MCL typically present with constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, night sweats, persistent fever, and fatigue. Approximately 25% of cases present with extranodal involvement with the bone marrow; peripheral blood and gastrointestinal tract are most often involved. In patients with extensive node involvement in the gastrointestinal tract, additional symptoms at presentation often include abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and bloating. Skin involvement in MCL is rare and usually indicates widespread disease.

According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, a diagnosis of MCL is established on the basis of the morphologic examination findings and immunophenotyping.

Immunohistochemically, expression of cyclin D1 in normal lymphoid cells is very low and often undetectable; only hairy cell leukemia shows moderate expression of cyclin D1. Therefore, positive immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 is pathognomonic for MCL. Increased expression of cyclin D1 protein leads to dysregulation of the cell cycle and stimulates uncontrolled cell proliferation. It is also indirect evidence of the chromosomal translocation (11;14)(q13;q32) on the CCND1 gene, which is detected in 95% of cases of MCL. In addition, negative expression of antigens may also help to differentiate MCL from other lymphomas. MCL does not usually express the antigens that are associated with germinal centers, such as CD10, CD23, and BCL6. Thus, these antigens can be used to distinguish MCL from B-cell lymphomas of germinal center origin, including follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends chemotherapy followed by radiation for stage I or II disease. In general, patients with advanced-stage disease benefit from systemic chemotherapy. Because MCL is clinically heterogeneous, treatment may require adjustment on the basis of the patient's age, underlying comorbidities, and underlying MCL biology such as TP53 mutations. During induction therapy, prophylaxis and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome is strongly recommended to be considered. Before treatment, hepatitis B virus testing is recommended because of an increased risk for viral reactivation with use of immunotherapy regimens for treatment.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by the proliferation of CD5-positive B cells within the mantle zone that surrounds normal germinal center follicles. MCL is a rare disease that most commonly presents in adult men (male to female ratio > 2:1) in the fifth and sixth decades of life. Individuals diagnosed with MCL typically present with constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss, night sweats, persistent fever, and fatigue. Approximately 25% of cases present with extranodal involvement with the bone marrow; peripheral blood and gastrointestinal tract are most often involved. In patients with extensive node involvement in the gastrointestinal tract, additional symptoms at presentation often include abdominal pain, abdominal fullness, and bloating. Skin involvement in MCL is rare and usually indicates widespread disease.

According to the guidelines of the World Health Organization–European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, a diagnosis of MCL is established on the basis of the morphologic examination findings and immunophenotyping.

Immunohistochemically, expression of cyclin D1 in normal lymphoid cells is very low and often undetectable; only hairy cell leukemia shows moderate expression of cyclin D1. Therefore, positive immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 is pathognomonic for MCL. Increased expression of cyclin D1 protein leads to dysregulation of the cell cycle and stimulates uncontrolled cell proliferation. It is also indirect evidence of the chromosomal translocation (11;14)(q13;q32) on the CCND1 gene, which is detected in 95% of cases of MCL. In addition, negative expression of antigens may also help to differentiate MCL from other lymphomas. MCL does not usually express the antigens that are associated with germinal centers, such as CD10, CD23, and BCL6. Thus, these antigens can be used to distinguish MCL from B-cell lymphomas of germinal center origin, including follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends chemotherapy followed by radiation for stage I or II disease. In general, patients with advanced-stage disease benefit from systemic chemotherapy. Because MCL is clinically heterogeneous, treatment may require adjustment on the basis of the patient's age, underlying comorbidities, and underlying MCL biology such as TP53 mutations. During induction therapy, prophylaxis and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome is strongly recommended to be considered. Before treatment, hepatitis B virus testing is recommended because of an increased risk for viral reactivation with use of immunotherapy regimens for treatment.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 69-year-old man presents for an evaluation for a 3-month history of generalized intermittent abdominal pain with occasional dark blood with bowel movements. He does not report experiencing any fever, chills, diarrhea, or obstructive symptoms. However, he does note a 10-lb weight loss over the past few months. He underwent routine screening colonoscopy 5 years ago, which was unremarkable. Complete blood count reveals normocytic anemia. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated extensive mesenteric lymphadenopathy and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy. Physical examination reveals an enlarged right inguinal lymph node, diffuse cutaneous erythematous plaques, and nodules with irregular borders on the upper back. Lesion diameters range from 0.5 to 1.5 cm, with the largest having a central ulceration.

A biopsy of one of the skin lesions was performed. Histopathologic examination demonstrated diffuse lymphoid infiltrate composed predominately of small, mature lymphocytes. Immunohistochemistry showed expression of cyclin D1, CD5, CD20, SOX11, and BCL2. Lesions were negative for CD10, CD23, and BCL6.

Swelling of the lower extremities

The patient is sent for lymphoscintigraphy, which showed impaired lymphatic drainage of both lower extremities consistent with obesity-induced lymphedema.

Lymphedema is a chronic condition caused by the abnormal development of the lymphatic system (primary lymphedema) or injury to lymphatic vasculature (secondary lymphedema). Chronic interstitial fluid accumulation may lead to fibrosis, persistent inflammation, and adipose deposition, which often results in massive hypertrophy. Obesity, which affects approximately 40% of the US population, is a rising cause of secondary lymphedema. Obesity-induced lymphedema (OIL) is a result of external compression of the lymphatic system by adipose tissue and increased production of lymph, which results in direct injury to the lymphatic endothelium. As BMI increases, lymphedema worsens and ambulation becomes more difficult, placing patients in an unfavorable cycle of weight gain and lymphatic injury.

The diagnosis of OIL is made by history and physical and is confirmed with diagnostic imaging. The classic presentation of lymphedema is edema of the lower extremities and a positive Stemmer sign. The Stemmer sign is positive if the examiner is unable to grab the dorsal skin between the thumb and index finger. The gold standard for lymphatic imaging is radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy. It involves injecting a tracer protein into the distal extremity, which should be taken up by the lymphatic vasculature and visualized in patients with normal lymphatic function. Lymphoscintigraphy has a high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (100%) for the diagnosis of lymphedema.

The risk for lymphatic dysfunction increases with elevated BMI. A BMI threshold appears to exist between 53 and 59, at which point lower-extremity lymphatic dysfunction begins to occur and is almost universal when BMI exceeds 60. Sixty percent of patients with OIL will develop massive localized lymphedema; the higher the BMI, the greater the risk for massive localized lymphedema. Typical areas of localized lymphedema include the lower extremities, genitals, and abdominal wall. In addition, patients with OIL are at increased risk for infections, such as cellulitis. Other complications of OIL include functional disabilities, psychosocial morbidity, and malignant transformation.

Patients at risk for OIL should be counseled and educated about weight management interventions, such as intensive treatment programs, lifestyle changes, and medications before their BMI reaches 50, a threshold where irreversible lower-extremity lymphedema may occur. Although weight loss may reduce symptoms of OIL, irreversible lymphatic dysfunction also may occur. Individuals at risk for OIL are often referred to a bariatric surgical weight management center.

Lymphedema management consists of compression regimens, physiotherapy, and manual lymphatic drainage. Adipose deposition in the late stages of lymphedema may decrease the response to such manual treatments. Operative procedures are typically used when these treatment options have been inadequate. Patients with chronic advanced lymphedema, in whom lymphatic impairment is accompanied by deposition of fibroadipose tissue, may also require debulking surgery.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is sent for lymphoscintigraphy, which showed impaired lymphatic drainage of both lower extremities consistent with obesity-induced lymphedema.

Lymphedema is a chronic condition caused by the abnormal development of the lymphatic system (primary lymphedema) or injury to lymphatic vasculature (secondary lymphedema). Chronic interstitial fluid accumulation may lead to fibrosis, persistent inflammation, and adipose deposition, which often results in massive hypertrophy. Obesity, which affects approximately 40% of the US population, is a rising cause of secondary lymphedema. Obesity-induced lymphedema (OIL) is a result of external compression of the lymphatic system by adipose tissue and increased production of lymph, which results in direct injury to the lymphatic endothelium. As BMI increases, lymphedema worsens and ambulation becomes more difficult, placing patients in an unfavorable cycle of weight gain and lymphatic injury.

The diagnosis of OIL is made by history and physical and is confirmed with diagnostic imaging. The classic presentation of lymphedema is edema of the lower extremities and a positive Stemmer sign. The Stemmer sign is positive if the examiner is unable to grab the dorsal skin between the thumb and index finger. The gold standard for lymphatic imaging is radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy. It involves injecting a tracer protein into the distal extremity, which should be taken up by the lymphatic vasculature and visualized in patients with normal lymphatic function. Lymphoscintigraphy has a high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (100%) for the diagnosis of lymphedema.

The risk for lymphatic dysfunction increases with elevated BMI. A BMI threshold appears to exist between 53 and 59, at which point lower-extremity lymphatic dysfunction begins to occur and is almost universal when BMI exceeds 60. Sixty percent of patients with OIL will develop massive localized lymphedema; the higher the BMI, the greater the risk for massive localized lymphedema. Typical areas of localized lymphedema include the lower extremities, genitals, and abdominal wall. In addition, patients with OIL are at increased risk for infections, such as cellulitis. Other complications of OIL include functional disabilities, psychosocial morbidity, and malignant transformation.

Patients at risk for OIL should be counseled and educated about weight management interventions, such as intensive treatment programs, lifestyle changes, and medications before their BMI reaches 50, a threshold where irreversible lower-extremity lymphedema may occur. Although weight loss may reduce symptoms of OIL, irreversible lymphatic dysfunction also may occur. Individuals at risk for OIL are often referred to a bariatric surgical weight management center.

Lymphedema management consists of compression regimens, physiotherapy, and manual lymphatic drainage. Adipose deposition in the late stages of lymphedema may decrease the response to such manual treatments. Operative procedures are typically used when these treatment options have been inadequate. Patients with chronic advanced lymphedema, in whom lymphatic impairment is accompanied by deposition of fibroadipose tissue, may also require debulking surgery.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The patient is sent for lymphoscintigraphy, which showed impaired lymphatic drainage of both lower extremities consistent with obesity-induced lymphedema.

Lymphedema is a chronic condition caused by the abnormal development of the lymphatic system (primary lymphedema) or injury to lymphatic vasculature (secondary lymphedema). Chronic interstitial fluid accumulation may lead to fibrosis, persistent inflammation, and adipose deposition, which often results in massive hypertrophy. Obesity, which affects approximately 40% of the US population, is a rising cause of secondary lymphedema. Obesity-induced lymphedema (OIL) is a result of external compression of the lymphatic system by adipose tissue and increased production of lymph, which results in direct injury to the lymphatic endothelium. As BMI increases, lymphedema worsens and ambulation becomes more difficult, placing patients in an unfavorable cycle of weight gain and lymphatic injury.

The diagnosis of OIL is made by history and physical and is confirmed with diagnostic imaging. The classic presentation of lymphedema is edema of the lower extremities and a positive Stemmer sign. The Stemmer sign is positive if the examiner is unable to grab the dorsal skin between the thumb and index finger. The gold standard for lymphatic imaging is radionuclide lymphoscintigraphy. It involves injecting a tracer protein into the distal extremity, which should be taken up by the lymphatic vasculature and visualized in patients with normal lymphatic function. Lymphoscintigraphy has a high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (100%) for the diagnosis of lymphedema.

The risk for lymphatic dysfunction increases with elevated BMI. A BMI threshold appears to exist between 53 and 59, at which point lower-extremity lymphatic dysfunction begins to occur and is almost universal when BMI exceeds 60. Sixty percent of patients with OIL will develop massive localized lymphedema; the higher the BMI, the greater the risk for massive localized lymphedema. Typical areas of localized lymphedema include the lower extremities, genitals, and abdominal wall. In addition, patients with OIL are at increased risk for infections, such as cellulitis. Other complications of OIL include functional disabilities, psychosocial morbidity, and malignant transformation.

Patients at risk for OIL should be counseled and educated about weight management interventions, such as intensive treatment programs, lifestyle changes, and medications before their BMI reaches 50, a threshold where irreversible lower-extremity lymphedema may occur. Although weight loss may reduce symptoms of OIL, irreversible lymphatic dysfunction also may occur. Individuals at risk for OIL are often referred to a bariatric surgical weight management center.

Lymphedema management consists of compression regimens, physiotherapy, and manual lymphatic drainage. Adipose deposition in the late stages of lymphedema may decrease the response to such manual treatments. Operative procedures are typically used when these treatment options have been inadequate. Patients with chronic advanced lymphedema, in whom lymphatic impairment is accompanied by deposition of fibroadipose tissue, may also require debulking surgery.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, Pediatric Lead, Obesity Champion, TSPMG, Weight A Minute Clinic, Atlanta, Georgia.

Courtney Whittle, MD, MSW, Diplomate of ABOM, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 52-year-old woman presents with bilateral pain and swelling of the lower extremities. She is 5 ft 6 in tall and weighs 376 lb; her BMI is 60.7. Four years ago, the patient was injured in a car accident, which limited her mobility; at that time her BMI was 39. She complains of difficulty using her legs and has developed periodic infections of the lower limbs, which have been treated at the wound clinic. Past medical history is significant for diabetes and hypertension, managed with metformin and lisinopril. She reports no history of penetrating trauma, lymphadenectomy, recent travel, or radiation. On physical examination, there is pitting edema of the lower extremities and a positive Stemmer sign bilaterally.

Decrease in cognitive functioning

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of late-onset Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is a neurodegenerative disease associated with progressive impairment of behavioral and cognitive functions, including memory, comprehension, language, attention, reasoning, and judgment. At least two thirds of cases of dementia in people ≥ 65 years of age are due to AD, making it the most common type of dementia. At present, there is no cure for AD, which is associated with a long preclinical stage and a progressive disease course. In the United States, AD is the sixth leading cause of death.

Individuals with AD develop amyloid plaques in the hippocampus and in other areas of the cerebral cortex. The symptoms of AD vary depending on the stage of the disease; however, in most patients with late-onset AD (≥ 65 years of age), the most common presenting symptom is episodic short-term memory loss, with relative sparing of long-term memory. Subsequently, patients may experience impairments in problem-solving, judgment, executive functioning, motivation, and organization. It is not uncommon for individuals with AD to lack insight into the impairments they are experiences, or even to deny deficits.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy, social withdrawal, disinhibition, agitation, psychosis, and wandering are common in the mid- to late stages of the disease. Patients may also experience difficulty performing learned motor tasks (dyspraxia), olfactory dysfunction, and sleep disturbances; develop extrapyramidal motor signs (eg, dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonian symptoms) followed by difficulties with primitive reflexes and incontinence, and may ultimately become totally dependent on caregivers.